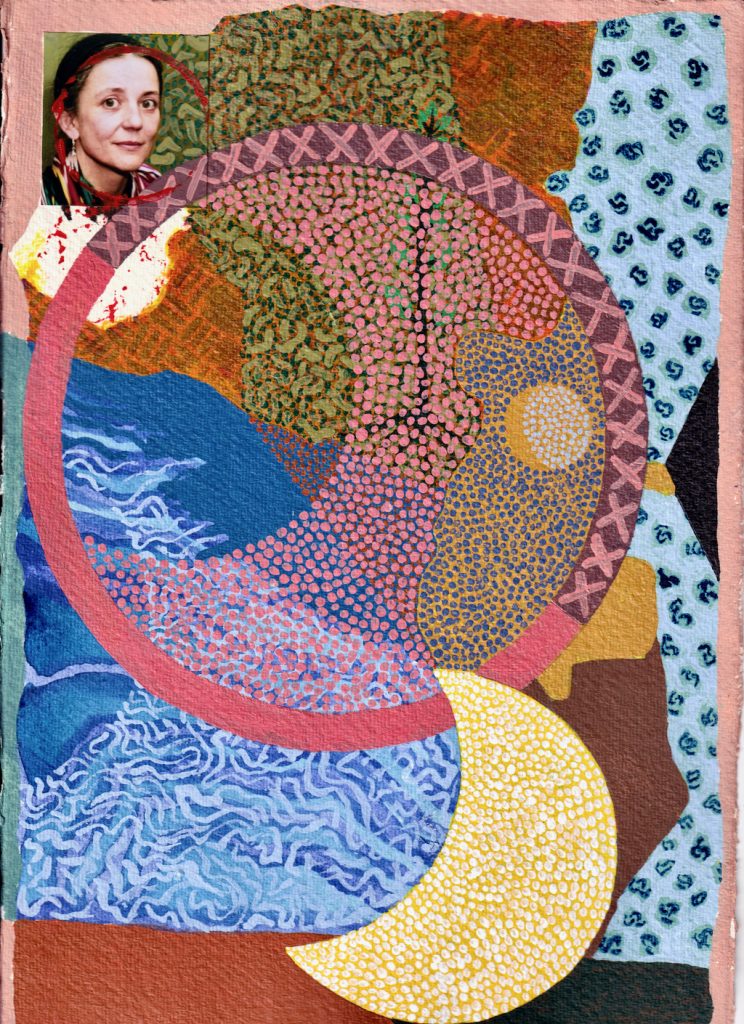

‘We seek questions rather than answers, or at least we will avoid rigid conclusions’.

UB

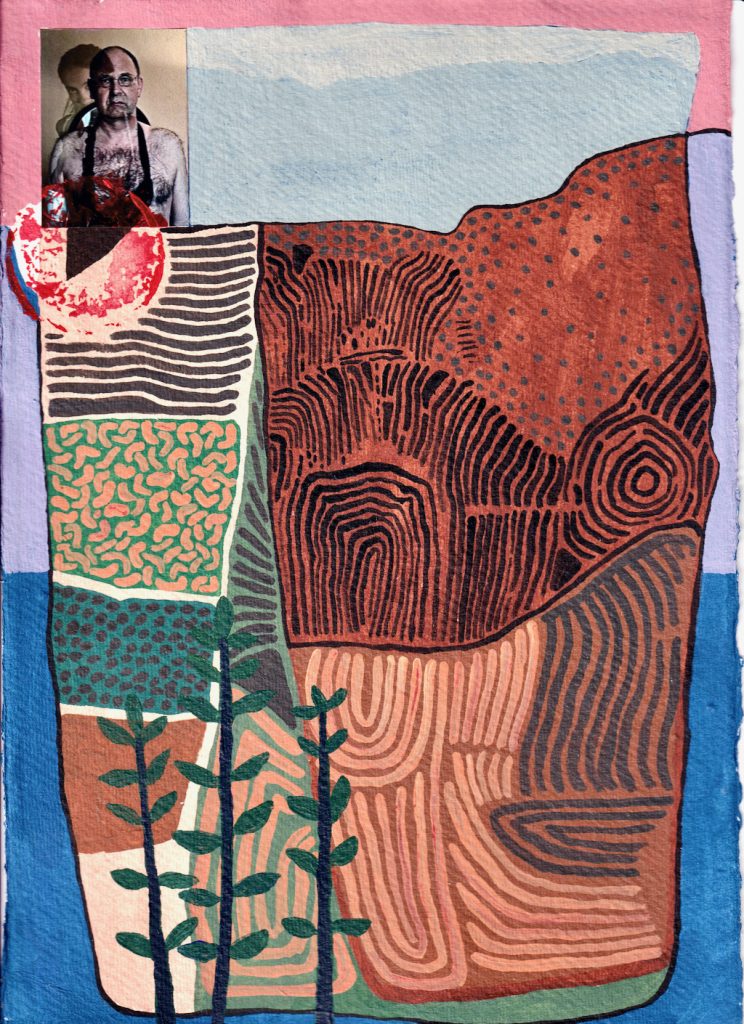

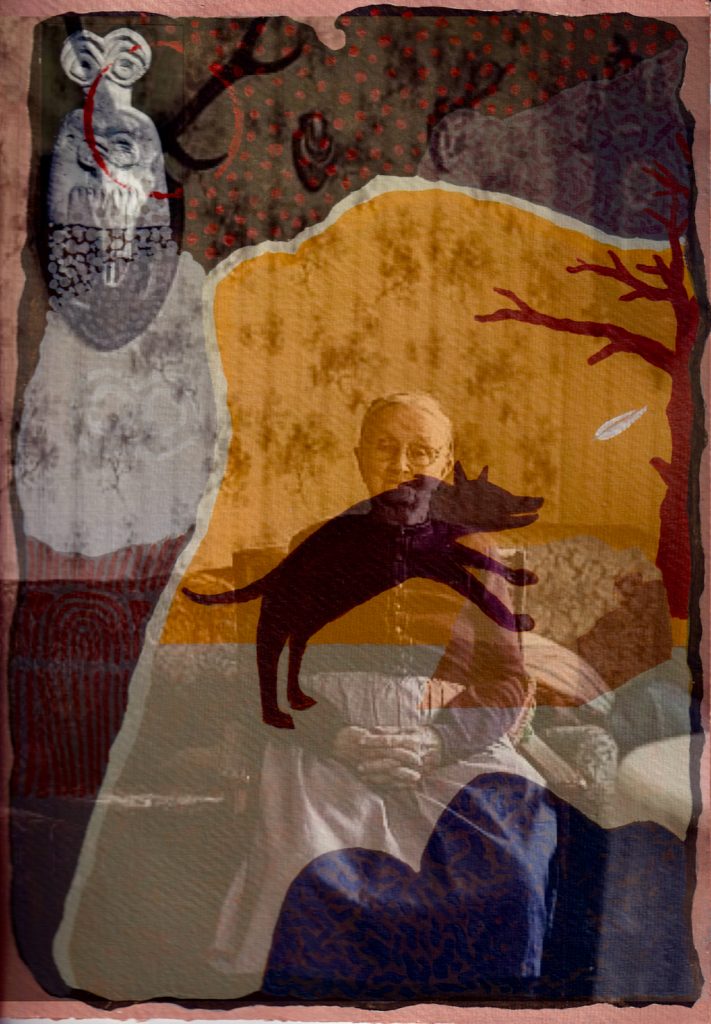

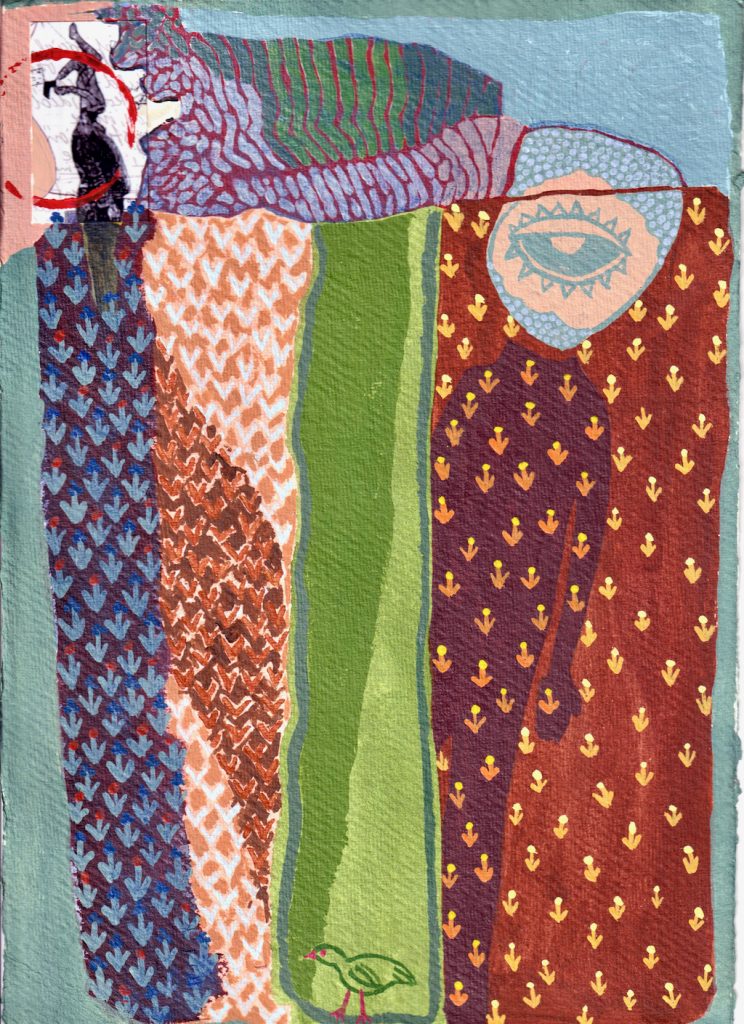

The last story of my father’s four stories involved Kirstie, my grandfather, and one of his friends. The two men went to collect oysters from a bed near Carbost that Kirstie regarded as her own. Discovering them there, she began to curse them roundly in Gaelic. His grandfather’s friend, a Professor of Ancient Middle Eastern Languages at Glasgow University, responded by cursing Kirstie back in some ancient tongue. The strange language and the solemn delivery disconcerted Kirstie so much she retreated, leaving the two men free to continue their task.

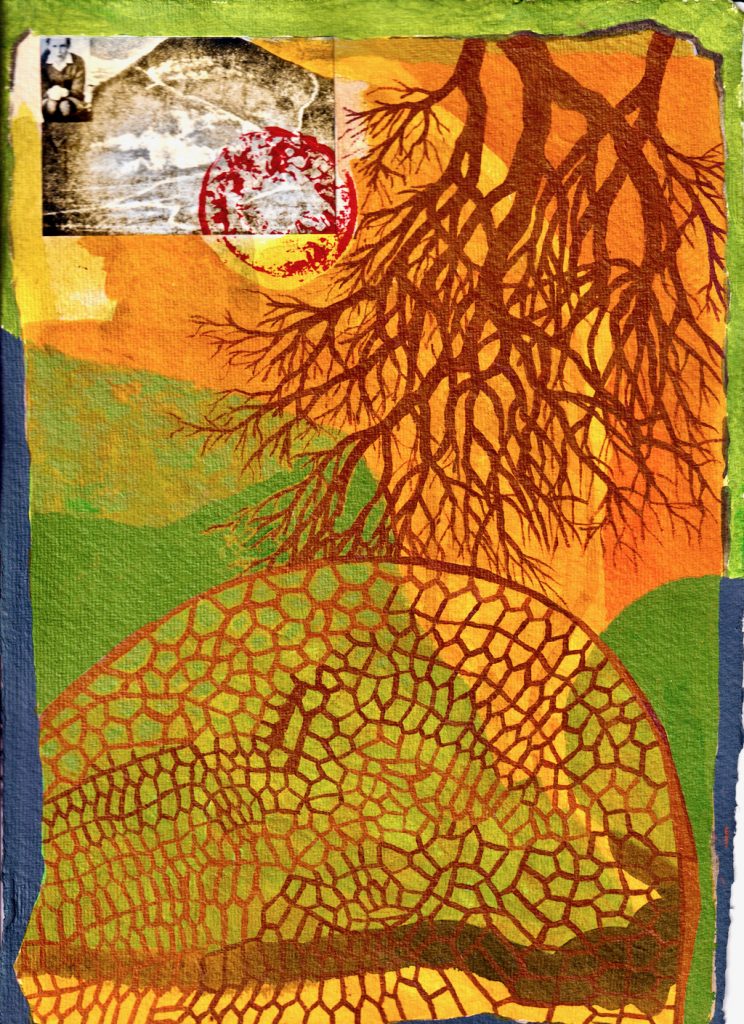

These four stories gave me a sense that places could be deeply uncanny. Perhaps they reflected my father’s sense of social tensions between the Elders of the Free Church of Scotland and the traditional beliefs and practices embodied in the figure of Kirstie, or perhaps a fascination with the uncanniness of hinterlands.

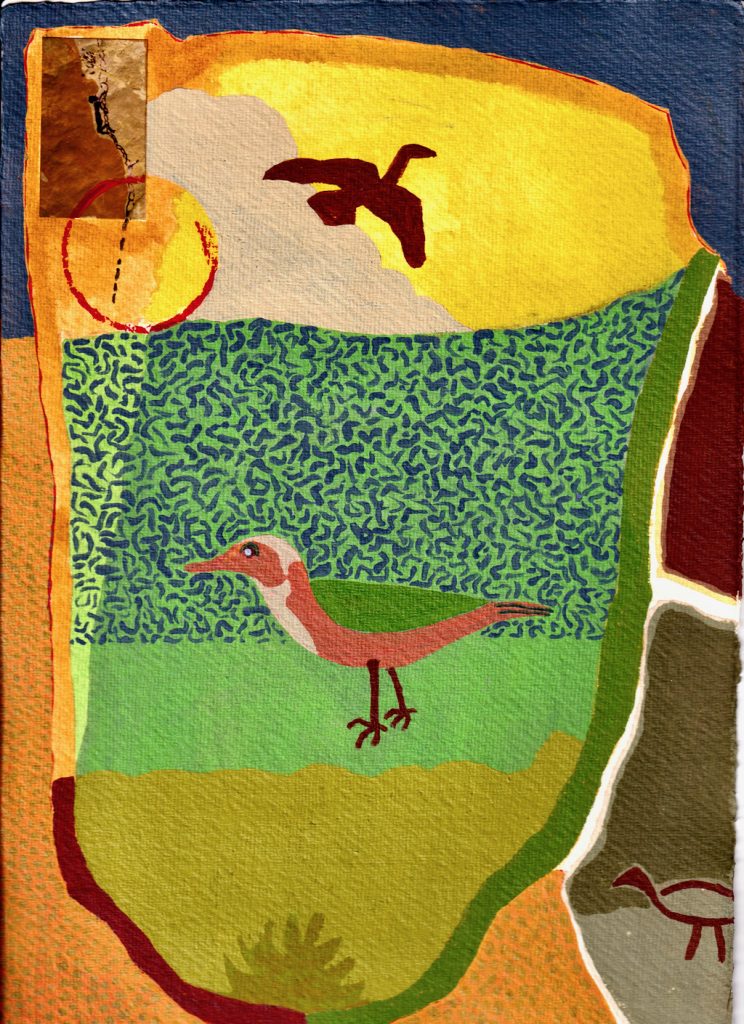

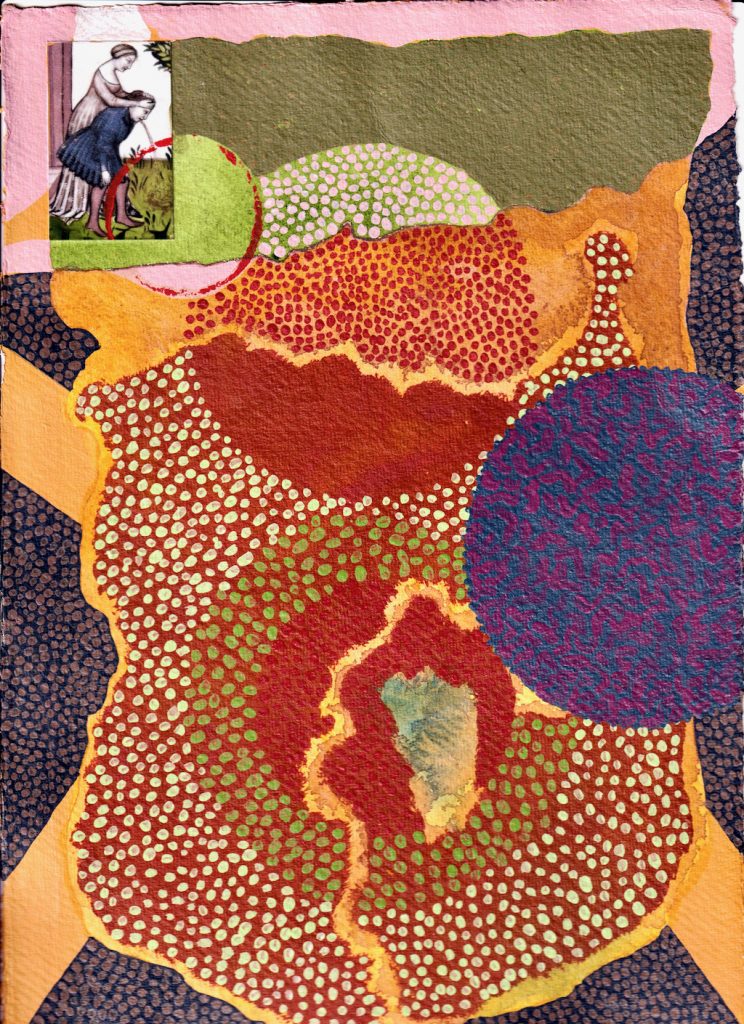

On Skye in 1945 “witch” would be “bana-bhuidseach” – literally bana: “female”, bhuidseach: “wizard, sorcerer, witch, sorceress”. In 1970 a man looked at the anthropologist Susan Parman and muttered “buidseachd” (witchcraft) when a truck got bogged down while moving peat since ‘woman did not usually go out to bring home peats’. (Susan Parman Scottish Crofters: A Historical Ethnography of a Celtc Village p. 125). English-language accounts of Skye’s folklore regularly refer to “witches” but there’s only one known legal allegation of witchcraft in the island’s history. There are, however, lots of formal letters from the Church Elders to the authorities asking them to take action against local woman identified as “witches”. Action not taken, perhaps because of the ambiguity inherent in “bana-bhuidseach”, which can also mean “wretch”, “scullery maid” or “temptress”. When one such letter was mentioned to a trusted local man, he replied that he had just recently employed a “wise woman” (in Gaelic boireannach glic), to “unwitch” his cow. It seems the authorities preferred not to attempt to disentangle one man’s bana-bhuidseach and another’s boireannach glic.