Borders mixed woodland

Introduction

Around mid-summer I spent some time visiting various mosses and other wetlands in the English / Scottish Borders. These included Ford Moss, a lowland raised mire to the south-west of Berwick-upon-Tweed; the three Whitlaw Mosses just east of Selkirk; and the Gordon Feuars Moss, a wet wood, just outside the village of Gordon.

This last is a very particular place, the remnant of a large floodplain mire dominated by a low tangle of birch and willow growing over a variety of fen and bog peatland habitats. It appeared entirely un-managed and, as such, made me think it might be some of the last “natural” remaining native woodland in Britain. However, on looking at a large-scale map later, I found that there are drains marked as running through two sections of the reserve: Gordon Moss Nature Reserve itself and the neighbouring strip known as Minister’s Bog. However a third area, Laird’s Bog, appears to be undrained, suggesting that there has been only minimum human intervention in the area in the past. That was certainly my impression ‘on the ground’.

What interests me is not, however, whether or not such a place is in some sense “pristine’, but how it fits into the shifting politics of land ‘improvement’ and environmental concern that is now starting to shape the Borders landscape.

Marker on the edge of Gordon Fears Moss.

In the ‘Laird’s Bog’ wet woodland at Gordon Feuars Moss

Wildness

A 2006 report – “A Borders Wetland Vison” – compiled for the Scottish Borders Council – tells me there are eleven distinct types of wetland in the region – blanket bog, lowland raised bog, fens or flushes, reed beds, coastal and floodplain grazing marsh, wet woodland, lowland meadows, upland hay meadows, purple moor-grass (Molinia), rush pasture, and lochs. All of these are environmentally important. (Peatlands, for example, reduce global climate change by acting as carbon sinks that capture and store carbon from the atmosphere. Twenty percent of the world’s terrestrial carbon is captured and stored in peatlands located in the northern hemisphere). I have two related reservations about this report’s neat definitions, however. The first is that surely one of the important qualities of wetlands is psycho-social rather than environmental as that term is usually understood – their quiet ‘wildness’ in Don McKay’s sense of that word. That is, their capacity “to elude the mind’s appropriations” (2001 p.21), even those provided by scientific organisations like environmental research consultancies. My second, related, reservation is that, in practice and perhaps somewhat ironically, it’s precisely human intervention that so often makes a nonsense of any such neat distinctions. (Wet woodland, precisely because it occurs as small areas of wood or localised patches in larger woods on floodplains, as successional habitat on fens, mires and bogs, along streams and hill-side flushes, and in peaty hollows, many of which border on cultivated agricultural or other land, often combines elements of many other ecosystems).

Repairing the old sheep fank on the Carter Burn near the entrance to Burns in the Wauchope Forest area.

Sign marking the entrance to the Burns.

The image of an old sheep fans above is located in what was once an area of upland hay meadow. It may originally have been bounded by wet woodland similar to that at Gordon Fears Moss and subject to regular flooding. The fank, however, is a product of the move towards land enclosure and the introduction of large-scale sheep farming. Then, beginning in the 1920s, sheep farming in this area was increasingly replaced by forestry, particularly the monoculture of Sitka spruce that now dominates the Wauchope Forest. Over the last eighteen years, I’ve watched this remnant of old upland hay meadow being further transformed; overrun by a mixture of bracken, reeds, and the beginnings of what may become a ribbon of deciduous wet woodland. While this process of change will continue one way or another, how it will fit into the wider pattern of future Borders land use is an open question.

The Midstream Collective

The Midstream Collective (left to right: CB, IB & MM)

I took the journeys indicated above because I wanted to get a sense of these wetland places ‘on the ground’ and to collect images. I was working towards a celebration of wetlands with my friends Christine Baeumler (an Associate Professor of Art at the University of Minnesota) and Mary Modeen (an Associate Dean at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design at the University of Dundee) for presentation at a conference in September. These are my partners in the Midstream Collective, which we set up some years back to ‘badge’ the collaborative work we wanted to do together.

As so often happens when I visit new places, the explorations with one end in view have set me thinking about another – land use on the Borders, both past and present – which in turn provoked this essay.

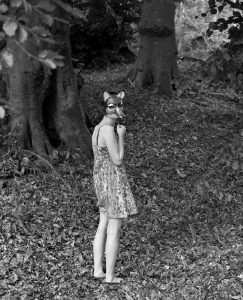

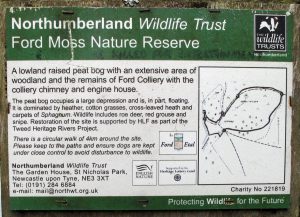

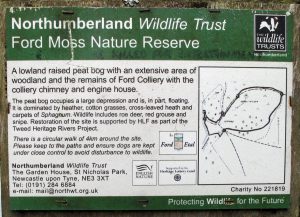

Ford Moss and its woodland

Ford Moss Nature Reserve sign

Ford Moss from the south-east

The Ford Moss Nature Reserve, wedged between a mix of farm land and old forestry plantation, is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) that sits in the hollow of a hill overlooking the Till Valley and the Cheviots. The Moss extends over about one hundred and fifty acres and is classified as a lowland raised mire. That’s to say its ecology is underpinned by a deep peat layer laid down by the rotting of vegetation over many thousands of years. The moss has become dryer over the last 250 years, but retains echoes of its older landscape form, which is undergoing ‘renovation’. The nature reserve includes old mixed woodland that’s adjacent to the moss and contains both mature Scots Pine and Oak.

I was unable to walk into the moss itself, which is fenced to keep people away from its “soft and treacherous surface”. Instead, I (largely) followed the circular two-mile path around its edge. The wildlife, particularly the birds, were present from the start, as indicated by the variety and volume of bird song, most noticeably of thrushes, blackbirds and skylarks. The persistent call of a buzzard hunting high over the moss accompanied me for much of the second half of my walk. I also had the luck to encounter a Roe doe at close quarters.

Broken snail shell – evidence of a thrush’s activity?

A buzzard calling high over the moss

Roe doe caught unawares

As I started walking around the moss, it struck me that the mature Scots Pine and Oak woodland bordering its southern side and situated on an incline, echoed descriptions of woodland I’ve read and thought about a good deal in the past.

Mature woodland on the slope to the south side of Ford Moss

This is the old woodland of the Jed Forest that had once covered an area of land called the Wauchope Forest, now largely taken over by commercial forestry. That area that interests me sits north and west of the Carter Bar pass on the Scottish side of the Cheviot Hills. (This is well down the Border to the south-west of Ford Moss in the old Middle March). The area I’m particularly attached to consists of three parallel low ridges with the Carter and Black Burn running between them into the Jed Water.

What came to my mind was that the woodland at Ford Moss was almost certainly of the same type that persisted, probably with relatively little change, from around the time of the end of the Roman occupation to some point in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, when the Lowlands were ‘improved’. (Jennifer Owen, in her magisterial Wildlife of a Garden: A Thirty-Year Study, suggests that by 400 AD. only 30% of England was wooded, although the percentage would have been considerably higher in the Borders). I regularly visit this area between Carter Bar and the former parish of Southdean when I’m in the Borders and have done so for almost twenty years now.

The politics of land use

The remains of Tamshiel Rig, photographed c. 2002. Fifteen years later this site, if it still exists at all, is completely inaccessible due to the density of the Sitka planting.

I stopped in Jedburgh on my way from Ford Moss to visit the land around Tamshiel Rig – a medieval shieling built on the site of what was once one of the best-preserved Iron Ages farms in Britain (until it was plowed up for forestry). While I was there I bought a copy of Peter Aitchison and Andrew Cassell’s The Lowland Clearances: Scotland’s Silent Revolution 1760-1830 (Tuckwell Press, 2012). Like so much historical research into social conditions in rural Scotland, it’s a stark reminder of how issues of social justice, ownership, and land use are intimately linked, of the complexity of those links, and of how the language of ‘progress’ has been used to justify the imposition of ‘top-down’ changes that have had long-standing consequences. (The authors reckon that the ‘improvement’ of Lowland agriculture traumatised, displaced, or otherwise disrupted, the lives of almost one third of the population. These were for the most part cotters, the poorest members of Borders society. In this context, it’s important to know that even today more than half of Scotland is still owned by less that 500 people, a situation with enormous socio-environmental consequences.

Two views reported in the book are relevant to my visit to the former parish of Southdean, where the population has been steadily declining year on year. The first is that of an establishment orthodoxy that views the enclosures and the improvements of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as a mark of unqualified progress. For that orthodoxy, the creation of “big new farms in place of common grazing” not only “completely altered the landscape of Scotland”, it ushered in the new, scientific agriculture essential to Scotland entering the modern industrial age (p. 72).

The second view is that of the historian Dr James Hunter. Hunter is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands, was the first Director of its Centre for History, and the author of thirteen books about the Highlands and Islands and that region’s diaspora. He was the first director of the Scottish Crofters Union, now the Scottish Crofting Federation and is a former chairman of Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Unsurprisingly then, he contrasts the “empty deserted glens” central to large-scale Lowland sheep farming and “kept going solely by vast, enormous subsidies from Europe”, with “the unimproved parts of Scotland … the crofting counties”, where “you see a much more viable society”. (p. 148) He also suggests that the people who resisted the ‘improvements’, where, from the perspective of our present eco-social situation, those with the better, more sensible, more economically and environmentally viable vision of the Scottish landscape than the “few subsidy junkies” who now dominate “rural Scotland where improvement was given full reign” (ibid).

Lindean loch information board.

Lindean loch.

The historical link between the loss of wetlands and ‘improvements’ of various kinds is neatly illustrated by what’s known of Linden reservoir or loch, located just east of Selkirk. Prior to the eighteenth century, this would have been the lowest, and possibly most extensive, of what are now collectively known as the Whitlaw Mosses. (The remaining three are ‘Murder’, ‘Beanrig’ and ‘Blackpool’ Moss).

Whitlow moss, looking west towards Lindean Loch

Whitlaw Moss.

Although the loch looks ‘natural’ enough today, it is in fact the product of two major human interventions. As a standing body of water, it’s largely the result of the extensive extraction of lime rich marl (a form of clay), dug by hand during the eighteenth century. Marl that was then used as fertiliser locally to improve the grass necessary for intensive grazing. Then, in the twentieth century, the loch was dammed to provide a public water supply for nearby villages, a situation that continued into the nineteen seventies. Now notable for its lime-rich water and soil, and for the six hundred and more plant and animal species apparently found in and around it, the loch was designated an SSSI in 1977.

Rethinking woods and wetlands – Kielder, Wauchope and other commercial Borders forests

Clear-felled area of hillside north of Kielder

Clear-felled area at Burns in the Wauchope forest

Given my long-standing interest in the area just north west of Carter Bar, someone familiar with the area would probably expect me to visit the Border Mires, the name given to a collection of peat bog sites in, and adjacent to, Kielder Forest in Northumberland, rather than the mosses I in fact visited. After all this area was, until planting began in the 1920s, predominantly open moorland and mire, with remnants of native upland woodland – some of it wet – along stream sides and in isolated craggy areas. Now it’s the largest man-made forest in Europe, with three-quarters of its six hundred and fifty square kilometres covered by commercial forestry, of which seventy-five percent is Sitka spruce. Like all such forests, it is a depressingly monotonous and oppressive environment that, typically, sustains very little in the way of wildlife and provides little employment.

There are, however, fifty-eight separate peat bog sites within the overall forest area. These are in remote locations and largely made up of deep lenses of peat located in larger areas of blanket bog. They can be up to fifteen meters deep in places and are almost all dependent on rainfall to maintain their water-balance. Taken together, they store more water than the Kielder reservoir itself, the largest artificial lake in the United Kingdom, which holds forty-four billion gallons, figure that reminds me forcibly of the importance of peat bog in the retention and general management of water, particularly in relation to flooding.

Kielder Water reservoir.

My problem with trying to visit the Border Mires sites is that, not only are they almost all in very remote areas, but they are also designated SSSIs and require permission to visit them. Given the contingencies of our family situation and of factors like the weather, this simply isn’t practical for me. So, over the years I’ve spent time in the area of Scotland just over the border from Kielder in places I would call ‘wet edge lands’. That is, places that historically have been radically reconfigured by climate change, then by human enclosure and, later again, by the forestry practices used to create the current forest monoculture.

The Black Burn, it’s banks damaged by industrial scale clear-felling, is now producing marsh-like areas along its upper length. These are frequently flooded and almost always remain waterlogged.

Roadside drainage ditch running into Carter Burn (2017).

The management of water in this area is now wholly determined by the needs of the forestry industry, in particular the quick and effective extraction of large volumes of timber. Crude roads built for this reason often disrupt the natural flow of water and, as a result, have a substantive impact on the two burns. The new drainage ditch pictured above now above runs directly into Carter Burn, and over time will almost certainly impact on its course and water quality. If it speeds up lateral erosion it may undermine the bank that separates the burn from the nearby pool and, in doing so, substantially change the course of the burn.

A standing pool, perhaps originally created by the silting up of an old flood meander in the Carter Burn, also shows some evidence of having been dammed at some point, perhaps to provide water in connection with the nearby fank shown earlier.

The Carter Burn valley

The images above are indicative of the area in which I go to walk, look, listen, and remember; that is to find ways into the numerous processes that produced, and are still producing, this landscape.

What’s to remember here? Many things, but in particular the continuous processes of both sedimented and sudden change. Before it was ploughed up and obliterated to plant forestry, there were the extensive and perhaps best preserved archaeological remains of an early Iron Age farm anywhere in Britain located just above Black Burn. For some three hundred or so years either side of the start of the Christian era, there is evidence that a milder climate made it possible to grow a primitive form of barley here. Later, in the medieval period, a bothy or sheiling called Tamshiel Rig was built near the site of the Iron Age farm. This provided shelter for those who tended the cattle that grazed here on the rich upland grasses each summer, part of a local agriculture based on transhumance. And to the east of the Rig, if local names are anything to go by, herds of swine once foraged for acorns in the oak woods and wallowed in the high mires above.

Why remember all this?

Because it tells us that present forms of land use are neither ‘natural’ nor inevitable. They are determined by the concerns of landowners and, as James Hunter indicates, there are always alternatives. That alternatives to the early modern culture of ‘improvement’ are now once again on the political agenda is clear from the Scottish Green Party’s policies.

A Borders cow and her calf (2017)

A Borders pig (2013)

Relevant Scottish Green Party policies: an indicative summary

The Scottish Green Party’s manifesto commits it to working to ensure that Scotland’s land benefits the many and not the few, and that to establishing transparency as to exactly who owns Scotland. It also argues for a radical programme of land reform to transform the social, economic and environmental prospects for communities across Scotland. To achieve this, it is committed to supporting such proposals as providing agricultural tenants with a right to buy their farms in appropriate circumstances, and to ensuring that public subsidy is directed at those in most need of it and to support the expansion of new sustainable forestry. All of which goes against the grain of the modern culture of ‘improvement’.

The Party is also committed to increasing local community control over public land and to working towards greater democratic control of the National Forest Estate and of property currently administered by the Crown Estate Commissioners. It is similarly committed to promoting community agriculture, involving a step change in making land available for smallholdings, with a shift away from high-input agribusiness to low-carbon, organic farming.

This dovetails into its proposal to support farming that provides public benefits, including rural jobs, water management, biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and shorter food chains. It aims to foster links between communities, local farmers and food co-operatives. It also recognises the need to support new farmers from non-farming backgrounds in getting access to the land and finding opportunities to build experience in environmentally and economically sustainable farming. It is committed to supporting large scale ecological restoration projects of native flora and fauna, including the continued restoration of internationally- important peatlands. Again, these policies largely go against the grain of the modern culture of ‘improvement’.

In principle at least, all these policies point to what could be a radical transformation of the Borders region, its agriculture, woodlands and wetlands.

A ‘wild’ speculation

So, what might an alternative Borders landscape look like? What, over and above Green policy, is needed to shift the Borders back to reflect something of the ‘unimproved’ landscape values that James Hunter identifies with a contemporary crofting culture, for example that of the Sleat peninsula of the Isle of Skye? The policies of the Green Party, if put into practice, would open the way for the establishment of a hybrid between traditional small-scale subsistence agriculture, alternative sustainable forestry practices, and the contemporary possibilities of tourism and other forms of income such as I’ve seen at first hand on Mull. However, the implementation of Green Party policies would require a radical political shift that would be resisted tooth and nail by those who own or are dependent on the big Borders estates. This suggests that there is little or no realistic possibility at present of reversing the depopulation of the Borders or of breaking the stranglehold of ‘subsidy junkies’; not just the owners of big farm estates and heavily subsidized grouse moors, but the many absentee landowners whose return on investment in commercial forestry depends on subsidy. However, we do not know what the impact of Brexit will be on the subsidy culture.

If I was asked to identify a point of leverage that might nonetheless help to move this process on, I would argue for the ‘re-wilding’ of the vast forestry monoculture of Kielder forest and points north of the Border. By this I do not mean aping a few wealthy individuals to import beavers or wolves onto their private estates. My sense of re-wilding owes more, as already suggested, to Don McKay’s understanding. Not, then, the re-introduction of a single large mammal but, as a start, small-scale human projects designed to reestablish areas of mixed forest, mire and moorland in the vast monocultural hinterlands of commercial Sitka spruce cultivation. Not, however, as stand-alone projects, but as part of a wider eco-tourism and cultural/environmental education initiative build in consultation with local people, particularly those young people anxious to remain and earn a living from the land.

The artist and environmental activist Cathy Fitzgerald has ably demonstrated, through her Hollywood Project, that it is both ecologically desirable and practically possible for an individual to learn how to gradually convert commercial forest monoculture to fully sustainable mixed woodland. What is needed is, above all, opportunity and a desire for environmental change. Given a multi-stranded approach that, for example, seeks to go beneath and beyond the macho reiving-related culture so heavily promoted across the Borders, it should be possible to start to construct a multi-stranded and locally grounded basis – looking both back to a ‘pre-improvement’ agricultural past and forward to new, technologically-enabled possibilities, a basis equivalent to James Hunter’s vision of renewal on Skye.