This post is the text of a presentation made at UWE for the Hydro-citizenship research network. Related material can be found elsewhere on this web site. An online broadcast of the talk and following question & answer session can be found at :

http://uwe.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=27652064-70b3-4384-920f-0ed5752aa53d

There’s no single definition of deep mapping. It’s a trajectory, a constellation of shifting impulses – in many ways ultimately educational – rather than a unified set of technical approaches or a creative methodology. However, historically it’s possible to identify two strands within this trajectory as reasonably distinct. So I’ll start with some history, then look at some specific projects, and end by suggesting where I think deep mapping is heading today. I should add that, perhaps because of my background in the visual arts, my approach is partisan rather than academic – hence my title.

Part One – two traditions

Broadly speaking one strand of deep mapping is text-based and the other performative and visual. The first is sometimes seen as a Regionalist genre of place-oriented writing, sometimes called ‘vertical travel writing’, and Americans insist it started in 1955 with Wallace Stegner’sWolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier. But in reality this text-based trajectory goes back much further and also includes books by Tim Robinson, W G Sebald, and psycho-geographers like Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd that don’t fit the US model. The second trajectory is predominantly European and uses various combinations of performance, site-specific multi-media work, and visual arts practice. Of course some individuals, myself included, happily borrow from both trajectories. So ‘deep mapping’ names a hybrid cluster of creative practices that draw on the humanities and/or the social and environmental sciences. It also regularly interbreeds with ‘memorial cartography’, ‘geo-poetics’, ‘haunted archaeology’, ‘psychogeography’, ‘theatre archaeology’, ‘experimental geography’, ‘site writing’, and ‘radical cartography’.

I’m going to refer to a small number of projects, most of which intervene inthe relationship between a physical location and the social processes of remembering and forgetting to reconstruct, relocate, and modify meaning. This intervention relates to Edward S Casey’s distinction – on the slide here – between ‘position’ and ‘place’. Basically, deep mapping challenges identity – of persons and places – as ‘position’ in Casey’s sense.

Mike Pearson, Michal Shanks, and Cliff McLucas cross-referenced their own archaeological, performance, social and architectural interests with William Least Heat-Moon’s 1991 bookPrairyErth (a deep map). This offers an exhaustive exploration of Chase County, Kansas, which is the last remaining expanse of tall-grass prairie in the USA. It weaves together ecological concern, ‘participatory history’, a wonderful chorus of quotations, and archival research, all playfully integrated through homage to Laurence Sterne’s C18th novelTristram Shandy. It’s slow, unstable, polyvocal approach that evokes the approach to deep mapping I most admire.

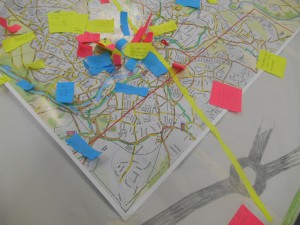

Art world people usually link deep mapping to the Situationists and Psychogeography, but its roots are equally in ‘vernacular mappings’ of the kind taken up by Common Ground. A current example of this vernacular strand is Luci Gorell Barnes’ The Atlas of Human Kindness – a growing collection of maps made by individuals and groups in Bristol, including refugee groups and children with learning difficulties. This shows where and when individuals experienced kindness from people concerned for their rights, feelings, and welfare. It invites debate about how kindness relates to place, exploring how stories, memories and imaginings make or re-make place; and how fragmented personal landscapes can become less fragmented. As such it helps us explore questions about value, connectivity, networks, and community.

In the 1980sMike Pearson, Michael Shanks, Clifford McLucas helped form a ‘theatre/archaeology’ for the radical Welsh performance group Brith Gof. In doing so they initiated the performative and visual trajectories of deep mapping in the UK. Their pioneering performances dealt specifically with place, identity, and the politics of spectral traces as these relate to cultural resistance and community. They creatively tensioned archaeological and architectural understandings of site with a culturally specific understanding of place embedded in the Welsh language. This work relates fairly directly to that of Lucy Lippard, Edward Casey, and Doreen Massey.

Brith Gof disbanded after Cliff McLucas’ untimely death in 2001, but Mike Pearson’s work has continued to inform deep mapping. His close attention to the ghosts, failures, and double meanings that haunt the excavation and archiving of all our places remains exemplary. But of course the dynamics of the performative/visual trajectory have continued to shift in response to psycho-social and environmental needs, as suggested by Alec Findlay and Ken Cockburn’s The Road North, which remaps Scotland through the lens of Basho’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

Part Two: ‘Deep mapping’ in practice

At the time of his death Cliff McLucas was working on a deep mapping project on the Dutch island of Terschelling, but we know far less about this late work than we should. However his work, and particularly the manifesto Ten things I can say about these deep maps, is growing in influence thanks to artist/scholars like Rowan O’Neil at the university of Aberystwyth.

Gini Lee’s Stony Rises deep mapping project is relevant here for two reasons. Firstly, it draws directly on McLucas’ work to develop its own intrinsic qualities – for example it’s use of physical acts of layering and incorporation. This additive approach also allows the project to echo the cumulative layering of sites as a process that has more than a purely material dimension. Just as places are constantly found, collected, disassembled and reassembled in memory, so each manifestation of this mapping writes and over-writes something of the life, events, performance, and ecologies of the Stony Rises region. Much of Gini’s recent work – she’s Professor of Landscape Architect at the University of Melbourne – addresses water-related concerns in relation to the Australian outback and its indigenous people.

Secondly,Stony Rises introduced the architectural writer, teacher and creative interventionist Jane Rendell to deep mapping. As Professor of Architecture and Art at the Bartlett School at University College, London, Jane opened up a hospitable educational space where deep mapping people could present and debate work with peers and graduate students. Genuine intellectual hospitality, vital to deep mapping as an ecosophical and educational praxis, is of course now as rare as hen’s teeth in the UK.

In the past such hospitality enabled productive dialogue between deep mapping and, for example, the urban therapeutics of Rebecca Krinke, a sculptor who teaches in the School of Landscape Studies at the University of Minnesota. We’re fortunate that researchers are now recognising the value of deep mapping and its networks elsewhere, for example at Groningen and Aalto Universities. It’s to be hoped that institutions with some genuine educational vision – for example the new undergraduate degree in Liberal Arts and Science at Groningen – will provide new intellectual spaces for the type of exchange that took place at UWE between Antony Lyons’ NOVA and the PLaCE research centre.

Of course small-scale, wholly independent deep mappings can be made and used to make highly original work – as the Scottish artist Helen Douglas has shown. The US writerand environmental activistRebecca Solnit, who worked with Helen on Unravelling the Ripple, also provides an interesting link to an early arts-led deep mapping in the USA.

Solnit’s writing on Lewis DeSoto’s Tahu-altapa Project – made between 1983 and 1988 – is particularly important in discussing an early US example of deep mapping. DeSoto’s ‘slow mapping’ project produced an installation that, chronologically and methodologically speaking, parallels the emergence of multi-media, performance-based deep mapping in Wales. The project documents and critically evokes the complex cultural and material shifts associated with ‘The Hill of the Ravens’ in the San Bernardino Valley. This later became a site for the production of marble and cement, and was renamed ‘Mount Slover’ by miners. The project traces the mountain’s material and cultural transformation over a substantial period of time and across three cultural and ethnic groups. As a multifaceted installation piece – now on permanent loan to Seattle Art Museum – it maps the destruction of this once-sacred site in ways that intersect with what Cliff McLucas would advocate in his later manifesto.

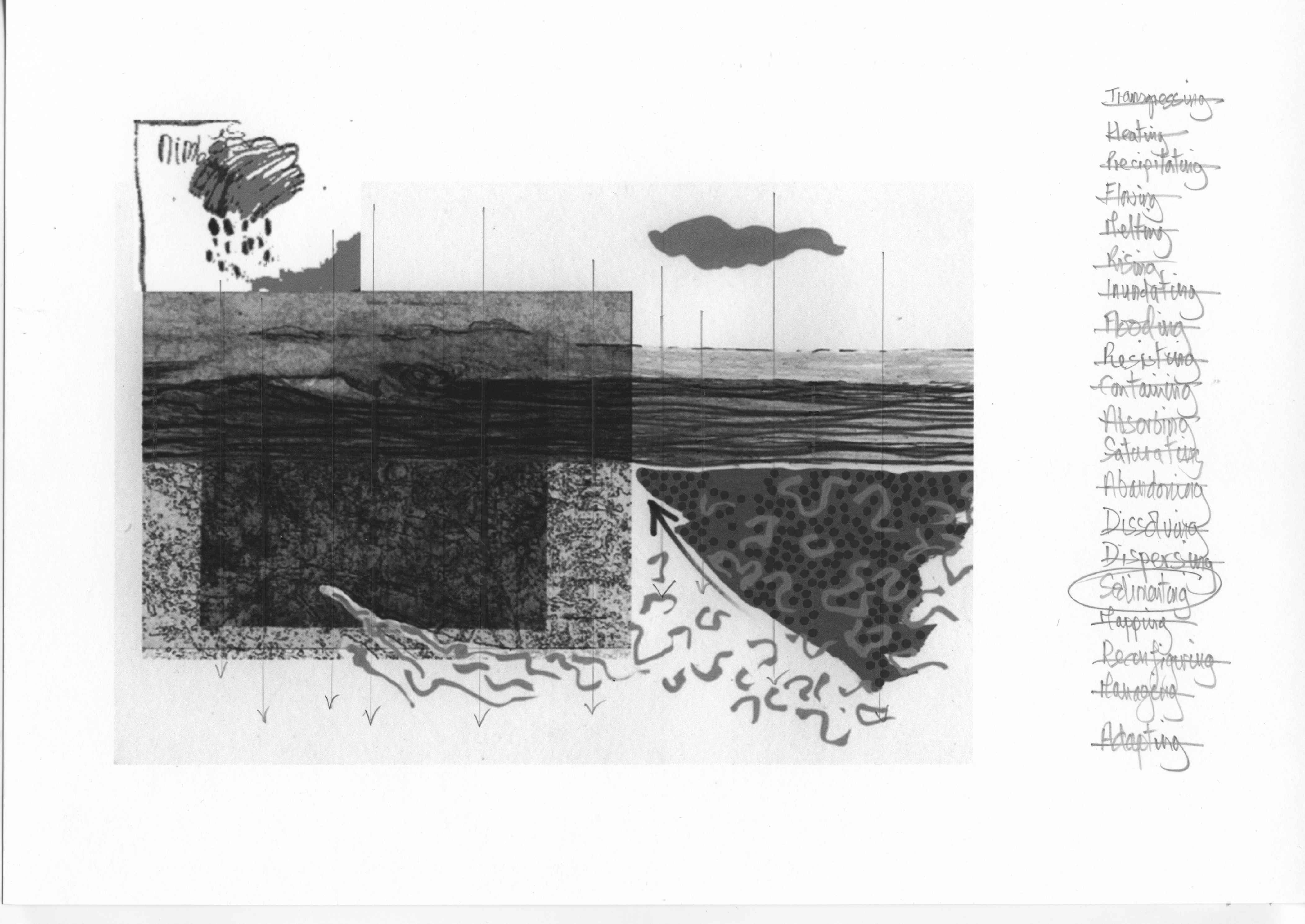

Michael Shanks suggests that deep mapping is about creating a “forced juxtaposition of evidences that have no intrinsic connection” – a process of “metamorphosis or decomposition”. This approach works against the grain of disciplinary exclusivity,re-narrating the world in ways not pre-conditioned by the realpolitik of an epistemological status quo that maintains a culture of possessive individualism. It’s for this reason that deep mapping cuts across the methods of the sciences and arts, playing with their relationship as a means to reconfigure social memory and place-identity. By activating testimonial imagination in response to the recovery of spectral traces of forgotten or untold pasts, deep mappings act educationally, critically bridging otherwise antagonistic positions and stories so as to provoke new understandings.

After fifteen years I‘ve come to see deep mapping as a way of ‘translating’ between distinct, often antagonistic, lifeworlds. It weaves together imaginative and scholarly strands of material and images precisely so as to do such bridging work. In the process it identifies and utilises gaps and frictions that allow us to see others and their place-identity and lifeworld differently. However, its focus on translation requires deep mapping to avoid identifying with any one lifeworld as a ‘world-unto-itself’, with what Casey calls a ‘position’. I refer to this avoidance as ‘disciplinary agnosticism’.

The notion of translation between lifeworlds – between collective narrative identities if you like – prompts questions about the relationship between the visible and invisible, presence and absence, love and loss. These questions are usefully raised in the chapter “Hauntings, Memory, Place” in Karen Till’s book The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place. She asks what it means to say that the spaces of a nation or region are haunted, or that ghosts are evoked through the process of place making? Even to ask such questions is to acknowledge an expanded sense of the present shot through with the past as social memory. Karen argues that we’re engaged in an unending process of mapping understandings of ourselves onto and through place and across time. Deep mapping uses testimonial imagination precisely in this way – to animate the possibility of collective self-understanding across different lifeworlds so as to recount and reconfigure taken-for-granted, forgotten or neglected social connections. In this respect it’s intensely political in the broader sense.

For example,Ffion Jones’ doctoral project is grounded in a complex family ethnography that’s included performing in a sheep byre on her parents’ farm in a remote Mid Wales valley. Her project aims (I quote): “to use ‘insider’ knowledge (lay discourse) as a way of exploring and extrapolating experiences of place within a rural farming family that confirms, contradicts and combines with academic discourses about our farming lives. As a researcher/farmer, I bridge two lifeworlds; my work seeks to look at a farming family’s attachment and experiences of place from the inside-out”. The project bridges lifeworlds usually seen as ‘given worlds-unto-themselves’, acknowledging and working with what’s valuable both in regional traditions and with external ideas and possibilities, creating conditions in which new coping strategies can emerge from inside the community.

I see Ffion’s work within a trajectory that deep maps a polyverse – as flowing from skills and understanding learned as a performer, daughter of farming parents, a scholar, a musician, a tenant upland sheep farmer, mother of a young child, and so on; as a re-imagining of place asa ‘simultaneity of stories-so-far’ in Doreen Massey’s sense. Her approach doesn’t reinforce a given identity or set of skills, a given understanding of community, or a fixed notion of self. Instead it invites us to take up the unending task of negotiating between such given positions.

Another way of thinking about deep mapping as translation is to relate it to Janet Wolff’s argument for a new approach to academic writing. Wolff argues that we need to work across and between three frames of reference, each of which I equate with one of Felix Guattari’s three ecologies as follows: an autobiographical or auto-ethnographic approach that grounds the work in lived contingencies – Guattari’s ecology of self; a commitment to the concrete and particular cultural object or event seen as indicative beyond itself – Guattari’s ecology of the social;and an obligation to challenge theory’s tendency to absolutism and its neglect of sensate, bodily knowledge – a bodily knowing I would link to Guattari’s ecology of the environment. Wolff’s thinking also converges with Ruth Behar’s account of the ethnographic essay as “an act of personal witness”, one that is “at once the inscription of a self and the description of an object” – and as both open-ended and able to desegregate “the boundaries between self and other”.

I’ve tested these and related ideas in a number of different contexts. For example with a project called A Grey and Pleasant Land? An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Connectivity of Older People in Rural Civic Society, funded by the ESRC.A small team of us worked with a farming and quarrying community in North Cornwall that increasingly dominated by urban “incomers”, many of them retired. Our task was to map the connectivity of this uneasy ‘community’ in depth.We focused on making visible the way different groupings within this community located themselves in relation to each other and to external authorities. Here some people struggle to maintain an identity embedded in a traditional taskscape, particularly when faced with the priorities of heritage tourism within the local economy. Despite excellent dialogue and support from groups like the local history society we failed to establish the web based deep map we had hoped to share, in large part because the team as a whole could not grasp that this type of work is not ‘interdisciplinary’ but ‘multi-constituency’ work, in which non-hierarchical ‘translation’ becomes central.

Another test project undertaken by two graduate students working with myself and Mel Shearsmith at the Parlour Showrooms on College Green in Bristol – part of a PLaCE collaborative project called Walking In the City. Both projects helped meto think about two interrelated aspects of deep mapping. The first, obviously, is that it enables us to translate, to intervene in the complex relationship between different social groups and between human and non-human beings – located in place and time – by facilitating the evocation of other images, telling of other stories. However if this was all it did there be little to distinguish it from many site-specific projects using relational aesthetics.

Deep mapping’s more radical function is implicit in Cliff McLucas’ insistence that it: “bring together the amateur and the professional, the artist and the scientist, the official and the unofficial, the national and the local”. Why this is necessary is implicit inBarbara Bender’s observation that [I quote]: “Landscapes refuse to be disciplined. They make a mockery of the oppositions that we create between time [History] and space [Geography], or between nature [Science] and culture [Social Anthropology]”. Both McLucas and Bender point up a growing, and ultimately political, tension between specialist knowledge based on epistemological exclusivity and a more holistic mesh of knowings and doings that recognizes a multiplicity of ways of understanding and acting in a polyverse.

To put this another way, we increasingly need to work in what the geographers Stephan Harrison, Steve Pile and Nigel Thrift call “the curious space between wonder and thought” – a space where, they insist: “there is no single Disciplinary (in an academic sense) voice”. This is one face of the space that deep mapping maps. The feminist philosopher Geraldine Finn calls this space (I quote) the: “space–between representation and reality, language and life, category and experience” – and it’s one that makes it possible to engage in (I quote): “the ethical encounter with others as the other and not more of the same – a space and an encounter that puts me into question, which challenges and changes me, as well as the other and the system that constrains and sustains us”. Its here, in the challenge to our given notions of mono-ideational authority, that deep mapping finds its most radical function and this encounter – unlike an ‘interdisciplinarity’ that remains safely within the control of academic thinking – changes our relationship to the world.

It does so because it puts our position in question – for example by challenging our reliance on disciplinary-based authority and membership of lifeworlds all-too-often taken to be ‘worlds-unto-themselves’. This shift can take place because the spectral traces that deep mapping works with are what Edward Casey calls “unresolved remainders” – ‘reminders’ that are the silences and gaps generated by official processes of remembering and forgetting. Exploring the personal and social resonances of those silences and gaps, and then drawing on those resonances so as to facilitate translation between antagonistic lifeworlds, is what keeps the trajectory called deep mapping vital.