Introduction / Points of departure

In an earlier draft of this essay[1] I wrote that it is intended for friends and colleagues in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland working on “rural” issues. Revisiting it, I have to acknowledge that this is not entirely true. It is also written to enable me to understand why Feral made me angry, why it seemed an attack on the ecosophical principles I have shared with friends and students for many years. What was it that that lurked just beneath the rhetorical surface of Monbiot’s righteous environmental indignation that smelled like the rankest possessive individualism, the conquest mentality that created the issues it claims to resolve?

The approach adopted draws on Geraldine Finn’s warning against ‘the traditional assumptions of high-altitude thinking, thinking forgetful of its contingent roots in particular persons, places and times’, and on her argument for placing greater emphasis on the task of ‘keeping alive local memory and imagination as a reservoir of meanings, truths, and possibilities for a different future’.(1996:137&141] Consequently I begin by acknowledging the convergence of circumstance and friendship that have animated this essay, an acknowledgement that also constitutes a declaration of interest.

I’m indebted to conversations with Lindsey Colbourne, the coordinator of Utopias Bach, about her tree nurturing activities, her ways of getting to know Dyffryn Peris since moving there in 2005, and about the impact of tourism in upland north Wales.[2] Conversations that were given additional significance by a doctoral candidate who introduced me to the conflict over the future of the Plynlimon in the Cambrian mountains where she lives. A conflict between the Summit to Sea project, supported ideologically by Monbiot’s Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life (2014) and in practice by his charity Rewilding Britain on one hand, and a local community that saw this as threatening its sense of place, its economic future and its Welsh-language cultural identity on the other.

An important circumstance was reading the dedication in my late parents-in-law’s copy of England’s Last Wilderness: A Journey Through the North Pennines (1989). This walking guide, by ecologist David Bellamy and environmental journalist Brenden Quayle is dedicated to ‘Walter, Old Willie, and all the Wild Men’, and was published within a year of the 1988 designation of the North Pennines as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). This area includes Weardale in County Durham, the home of my wife’s maternal ancestors and a place that I’ve visited annually for some forty years. This reference helped contextualise the issues in Wales and the “Wild Men” mentality by linking them to my experience of an upland place that has much common with Plynlimon.

I’m also indebted to my friend Rowan O’Neill, who suggested me as a speaker to a group of Welsh artists and academics. A group setting out to address the issues raised for rural areas like upland communities by post-Brexit change, including interventions like the Summit to Sea initiative, and with which I’ve subsequently worked as a consultant. I was at that time involved in similar work taking place in both the Irish Republic and Scotland and studying with Haumea, an online initiative delivering eco-literacy education set up by the forester, educator, eco-activist and artist Cathy Fitzgerald. I’m also indebted to Ewan Allinson for help with information and for a sharing of interests and concerns.

As the above makes clear, what follows is not “objective” in the usual academic sense. Rather it is informed by, and respects, friendships and loyalties both new and old.

‘It is no extravagance to formulate the problem of the future …in terms of

imagination’.

Paul Ricoeur’s detailed articulation of ‘political imagination’ (in Kearney 1996:3), together with Richard Kearney’s elaboration of its structural dynamics (1991), provide one point of reference for this essay. Felix Guattari’s understanding of the interrelationship of the three ecologies of self, society and environment, another. (Genosko 2008) It is on the basis of the interaction between such ideas and my lived experience that I suggest that Feral is predicated on a flawed amalgam of ungrounded utopian vision, an outdated conception of self, an inflated projection of a personal predilection, and a reductive approach to complex psychosocial and place-based issues.

George Monbiot’s almost obsessive identification with rewilding is shot through with assumptions, both explicit and tacit, about a heroic, risk-taking masculinity he sees as intolerably restricted by the demands of contemporary life. A form of life he sees as no longer able to offer him access to the ‘high, wild note of exaltation’ he craves. [2014:26] An experience of exaltation that is, none the less, very largely dependent on the mediating socio-economic circumstances that provide him with the financial means, leisure time and possibilities of ownership necessary to afford him such experiences as a solitary encounter with a freak wave and eye-to-eye contact with a large bull dolphin in the wild. In short, his wilderness experience is highly mediated by his location within the economics of the culture he desires to escape.

My main concern here is not, however, with the intertwining of a rewilding mentality and the American-inspired Adventure or Risk culture predicated on marketing the experiences of exaltation that preoccupy Monbiot. Rather it is with the psychosocial circumstances necessary to effect ecosophical action. I want to sketch out a basis for a political imagination on which to establish genuinely ecosophical approaches to the changes needed in order to prevent both ecological and social collapse. Nothing in what I write is intended to diminish our need to respond to the deplorable state of the UK’s rural ecologies, or as an argument against the judicious and appropriate reforestation of land in places like Plynlimon and Weardale. My exposition does however require accounting for the flaws Feral exhibits. Flaws that, as I hope events in the Welsh uplands will subsequently show, are counterproductive to its author’s aims and damaging to the need to realise genuinely ecosophical change more generally.

The persistence of wilderness thinking

The publication and reception of Feral indicate that, despite the considerable volume of thinking (e.g. Solnit 1994 & 2001, Cronon 1995, Schama 1995, Jamie 2008, Ray 2017) that unpacks uncritical identification with ‘the sublime and the frontier’, (Cronon 1995:3) or with an Edenic thinking that perpetuates Western civilization’s ‘oldest story’ (Solnit 2001:12), such identifications persist regardless. It is important to acknowledge that they do so in no small part because encounters with wilderness, despite this being a highly particular cultural construct, remind individuals that they are inseparable from the ecological systems that sustain their lives. Experience of what is called wilderness is both a source of genuine wonder and insight and a marketable cultural product eulogised as the habitat of what Kathleen Jamie names ‘the lone enraptured male’. (2008). Analysis of the socially problematic historical, cultural, gendered, and ableist aspects of the wilderness mentality has not diminished it, since it is now the basis for a heavily-marketed international Adventure or Risk industry as a sub-set of global tourism.

What follows will reject the dominant conception of both rewilding and the self to take up a specific view of place and placed-ness linked to an understanding of self-as-community; one that values ‘emotional intimacy, anthropomorphic empathy, aesthetic appreciation and ritual devotion’. (Hillman 2006:335) An approach currently being explored in practice in Wales through the experiments of Utopias Bach.[3] Grounded in a testimonial relationship to place, this is a small-scale utopianism enacted in day-to-day life via the playfully critical spirit of endeavours such as Fluxus. It offers, that is, an adventurous alternative to the inflated, ungrounded utopianism that animates Feral’s case for rewilding. In what follows I have viewed Feral on the basis of Kathleen Jamie’s injunction that: ‘if we read about “nature” or wild places, it pays to wonder, who’s telling me this, who’s manipulating my responses, who’s doing the mediating’? (2008:3).

A failure of eco-ethical imagination

This approach assumes that Feral is intended to have real effects in the world. For example, that its violent attack on upland sheep farming in Wales is intended to prepare the ground for large-scale blanket rewilding through projects such as Summit to Sea.[1] Support presumably intended to counter any public concern about the psychic and socio-cultural consequences of such a project on the small and economically vulnerable upland Welsh community it would effectively displace and dismantle.

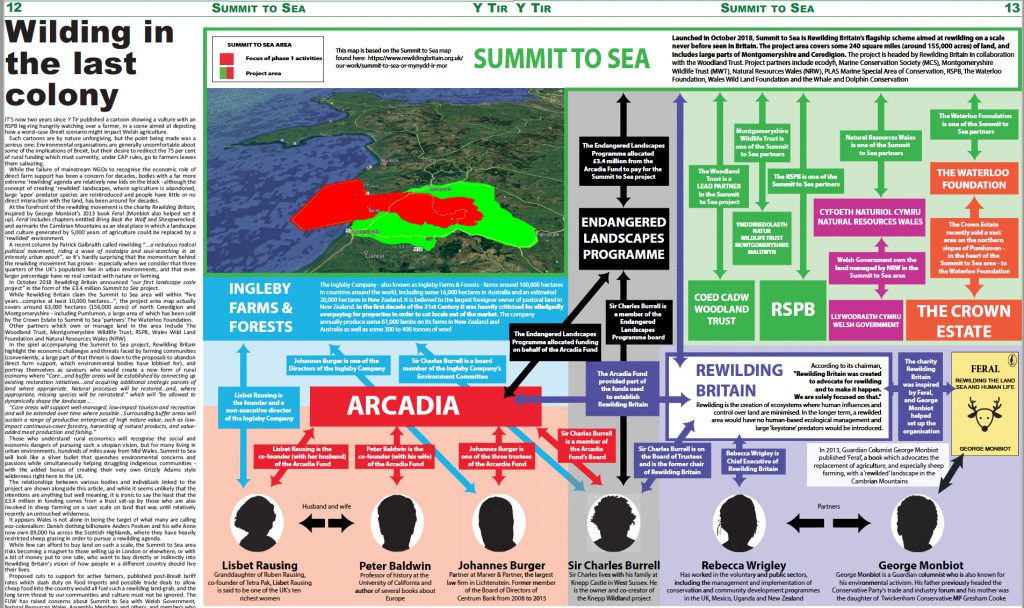

Fig. 1 ‘Wilding the Last Colony’ Y Tir, April 2019

I won’t elaborate on Monbiot’s position when, in its April 2019 edition, Y Tir produced an Illustrated article pointedly entitled ‘Wilding in the Last Colony’. [See Fig. 1 above]. This sets out the network of influence and funding sources behind the first iteration of the Summit to Sea project, which included Monbiot’s Rewilding Britain charity. It is sufficient to say that, given the role the vilification of sheep and upland sheep farming central to his promotion of “rewilding” Monbiot, himself a highly paid investigative journalist, was unwise to join an alliance that received funding from the Ingleby Company, owners of farms in New Zealand and Australia that annually produce over sixty thousand lambs and between three and four hundred tonnes of wool.

Richard Kearney argues that imagination has ‘crucial ethic powers’ in addition to ‘poetic powers’; ethical powers vital to our taking action and that he summarizes as: ‘the utopian; the testimonial; and the empathetic’. (1993:218) He views the testimonial imagination as putting ‘itself in the service of the unforgettable’, as an act of witnessing, (ibid:223), arguing that if the utopian imagination fails to attend to such witnessing it: ‘risks degenerating into empty fantasy’ because ‘it forfeits all purchase on historical experience’. (ibid:220) It is in just this respect that I suggest Monbiot’s ungrounded utopianism is deeply problematic. For reasons I will discuss later, it floats free of the lived historical experience of those his proposals would most immediately effect. Such a version of rewilding implies, as the ecologist John Rodwell points out, a degree of forgetfulness of the past that could be ‘considered a pathology’. (2010: 21) In terms of the political imagination as Ricoeur and Kearney understand it, Monbiot’s selectively citing extensive economic and scientific “facts” in support of rewilding is, in terms of the imagination required by an effective politics, largely beside the point.[5] As the inclusion of the word ‘colony’ in the title of the Y Tir article suggests, Feral’s failure of imagination lies in failing to take account of the deeply felt consequences of the historical experience of those communities it would most directly affect.

How not to initiate ecosophical change

Feral opens by establishing Monbiot’s self-proclaimed status as a “wild man” happy to eat live grubs on the basis of memories of former adventures in the South American jungle. It goes on to tell the reader of his admiration for a man ‘who had abandoned comfort and certainty for a life of violent insecurity’ and who, despite his slim chance of ‘coming out alive, solvent and healthy’ from the dire situation in which he had placed himself may, in Monbiot’s eyes, have made the right choice. (2014:2) In short, it begins by signalling the author’s preoccupation with risk and the ‘high, wild note of exaltation’ obtained in the wild; (ibid) the same preoccupations serviced by a growing Adventure Culture predicated on selling “wilderness”. (Ray in Ray & Sibara 2017:29) We are also told that, having moved to rural Wales, Monbiot felt diminished by the ‘smallness’ of a lacking the uncertainty, fear, courage, and aggression that he believes ‘evolved to see us through our quests and crises’. (2014:6) (A view at odds with a growing scientific view of evolutionary development that stresses the importance of social bonding and cooperative).[6] Consequently, a reader might be forgiven for thinking that statements like: ‘Rewilding, to me, is about resisting the urge to control nature and allowing it to find its own way’ (ibid.:9) are primarily an expression of the author’s own internal conflicts.

For this reader the most disconcerting aspect of Feral is not the implication of the arguably questionable use of scientific “evidence” to support its case. (Scientific data always being dependent on framing and interpretation for its social meaning). Rather it is everything Monbiot fails to address. Feral was published eight years after Kathleen Jamie’s A Lone Enraptured Male, a review of Robert Macfarlane’s The Wild Places, which illuminates the problematic assumptions that run through popular attitudes to “wild” nature. Monbiot’s blithe disregard of the issues Jamie raises is reflected in his failure to acknowledge the influence of class, gender, nationality, and the legacies of colonialism in his notion of wilderness. Furthermore, Feral fails in the terms H. L. Mencken uses to define good journalism, namely that: ‘It should “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted”’.[7] It is hard to avoid seeing Feral as written specifically to confirm the prejudices and ignorance of a particular, comfortably-off, “environmentally conscious” urban readership that regards places like the Welsh uplands as little more than holiday destinations. Its argument is made at the expense of remote upland rural communities it claims survive only because supported by its readers’ taxes. This, and it’s vilification of sheep and those whose identity and precarious economic survival depends on them, is an apt measure of Monbiot’s balancing of “comfort and affliction”.

The significant absences in the grandiosely titled Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life are legion. Given that title, it would not be unreasonable to expect Feral to offer less autobiography and more careful contextualisation. It might be expected to include, in no particular order, most or all of the following points. Consideration of the relative merits of blanket reforesting versus the judicious restoration of bog in upland Wales, given both that the latter is three times more effective in terms of carbon capture than the former and the location of the watersheds of the Severn and Wye rivers. Consideration of issues related to forest farming with regard to the diversification of habitat and the need for a sustainable human economy, both seen in the context of the inevitability of increasing food security issues. A detailed discussion of private and corporate land ownership and of access to existing woodland.[8] A balanced assessment of social benefit between investment in urban greening measures and large-scale rewilding. Of particular importance given that urban greening enhances the quality of life of the large element of the population financially debarred from Adventure tourism and in countering pollution through such strategies as planting green screens around schools. Critical consideration of Government subsidy to the privately-owned grouse shooting industry over a period when the Environment Agency, which serves the public good, has suffered substantive funding cuts. Consideration of the distortion of environmental debate by a media industry geared to an audience without lived experience of the rural working communities it is increasingly encouraged to denigrate, and of the political and economic interests that denigration serves. Particular consideration of the ways in which “rewilding” is entangled in global networks of economic investment in tourism and lucrative Adventure-related industries. Most importantly, however, consideration of the relationship of such specific issues and socio-environmental concerns to long-term infrastructural, energy and social well-being issues.

Feral merely nods to, skirts over, or ignores such issues. Instead we are given the chapter ‘The Beast Within (Or How Not to Rewild)’ that tries to distance Monbiot’s proposals from those of politically authoritarian regimes by insisting that rewilding must not be imposed by Governments. There is no analysis, however, of large-scale rewilding currently being conducted by business interests and wealthy individuals, or of how public rejection of Government intervention would favour such individuals and businesses. All this despite our being told that rewilding should not aim to produce ‘a paradise for the rich’ extracted ‘from the lands of the poor’. (2014:208) Monbiot takes care to reference Simon Schama’s exoneration of modern environmentalism from any kind of historical kinship with totalitarianism. This is particularly disingenuous, since it is used to support Monbiot’s claim that ‘large-scale restoration of … natural processes can take place without harming anyone’s interests’. (ibid.) Perhaps it can. However Monbiot chooses to ignore the racist, elitist and ableist attitudes that informed rewilding in North America and continue to constitute the less savoury aspects of the ‘corporeal unconscious’ of the contemporary Adventure and Risk industries. (Ray 2017). The second half of Rebecca Solnit’s Savage Dreams: a Journey into the Hidden Wars of the American West, focused on Yosemite National Park, demonstrates just how far from the truth Monbiot’s claim about the harmlessness of rewilding is. To read Feral in the light of Solnit’s exposition is to be made aware of a number of uncomfortable parallels between the treatment of Native Americans in the USA and the more insidious, but ultimately no less coercive, forces that Monbiot argues should be applied to Welsh-speaking upland farming communities.[9]

[1] What follows here is an essay in the sense Ruth Behar gives the term, namely: ‘an act of personal witnessing’. (1996:20).

[2] See https://lindseycolbourne.com/fy-milltir-sgwr-my-own-projects-and-interventions

[3] See https://www.utopiasbach.org

[4] See http://www.summit2sea.wales

[5] See Hillman J 2006: 335 for the reasoning behind this assertion.

[6] See, for a recent example of this in magpies:

https://www.sciencealert.com/scientists-attached-tracking-devices-to-magpies-that-s-when-things-got-weird?fbclid=IwAR3KPFTlmTzRiy__5HtKAQK0mKeyWZgLo3ZwRQKyh_76xhJk008ocR1Igxk

[7] Quoted by Will Self, see https://www.vice.com/en/article/kwpvax/will-self-charlie-hebdo-attack-the-west-satire-france-terror-105

[8] See, for example, Fowler 2020, Hayes 2020.

[9] Forces independently discussed in some detail by Monbiot’s critic, Dafydd Morris-Jones, see https://play.acast.com/s/bbccountryfilemagazine/rewildingwiththreatenwelshculture-saysfarmerdafyddmorrisjones

Pingback: Meeting the Land at Found Outdoors – James Aldridge – Art, Ecology and Learning