This text is from a presentation given to students on the Arts and Humanities Masters programme at Duncan of Jordanstone School of Art and Design, University of Dundee on 20/11/2018.

Since I’m going to offer you a provocation about un-disciplining art practices, I need to start by clarifying what I mean by this. My concern is with un-disciplining the framing of creative practices, freeing them from disciplinary authority so as to open up other, more relational conversations between creative practices and the world. I’ll begin with the general crisis in disciplinary thinking, move on to more specific disciplinary issues relating to creative practices, and then share some examples of undisciplined practices.

Why does the university system assume that, although I know nothing about you or your work, I will have something useful to say to you? That assumption rests on our being categorised by discipline – and on the belief that disciplinarity is the best basis for transmitting knowledge. But to say that Andrea Fraser and Jeff Koons share a discipline actually tells us nothing of real value. So, might there be another reason why we’re all here together in this room?

Jane Bennett, reflecting on Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming-animal’, observes that this childhood game: “suggests that children have a sense of themselves as emerging out of a field of protean forces and materials, only some of which are tapped into by a child’s current, human, form”. This sense of protean possibility – linked to empathetic imagination – usually fades as children internalizesocial norms. However Bennett’s claim might be extended to those adults who have a real desire to stay in touch with protean forces and materials, including those who feel a need to make art.

Increasingly, the assumptions that underwrite disciplinarity are being questioned. Isabelle Stengers is a Belgian professor of philosophy. She trained as a chemist and has won international acclaim for her work in the philosophy of science. Starhawk is an American writer, teacher, activist and leading exponent offeminist neopaganism and ecofeminism – or, as she might say, a witch. From the perspective of disciplinarity, these two women are separated by an unbridgeable divide. Yet in Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell, Stengers and her co-author present Starhawk as somebody reclaiming an art of participation that deals directly with pragmatic concerns about effects and consequences. That’s to say, they identify her as somebody able to tap into, and work with, Bennett’s sense of protean forces. Somebody involved in: ”the dangerous art of animating in order to be animated”; in transforming our capacity to affect and be affected. That capacity is, of course, what many people claim for art, so it’s no surprise that Stengers sees Starhawk as having what Felix Guattari would call an ‘ethico-aesthetic practice’.

The disciplinary system is in crisis because it can’t engage with the Earth as a complex adaptive whole – a nested system of ecologies, all dynamically interacting and continuously forming new structures and patterns of relationships that aren’t easily isolated or predicted. Un-disciplining art practices is a response to this failure. It involves rethinking the relationship between imaginative activity and the disciplinary discourse that positions art in terms of possessive individualism. A discourse that, to maintain its own exclusivity, needs to isolate art from the kinds of fluid, shared, more-than-human, energies sensed inthe game of ‘becoming-animal’.

So, maybe we’re not in this room just because of disciplinarity.

Stengers and Starhawk both want to counter the deadening effects that disciplinarity enacts through its overwhelming compulsion to separate, categorize and judge. They want us to remember that we are always both more and less than the categories that name and divide us.The disciplinary compulsion to separate, categorise and judge divides the world into ever-smaller fragments that are supposed to increase our knowledge. But, because we live in a multi-layered, dynamically interacting, and continuously forming multiverse, it actually does the opposite. What we now desperately need are relational understandings– ways of thinking that acknowledge that all phenomena are ultimately inter-related and inter-dependent. However, for the moment the disciplinary mentality is still dominant. It judges all forms of knowledge and value claims according to its own hierarchical criteria. That’s why, when artists get doctorates, they’re made Doctors of Philosophy, not Doctors of Art. In the disciplinary system, philosophy is the ‘queen of the sciences’, while art isn’t considered capable of producing proper knowledge at all.

We can’t step just away from the disciplinary system, but we can be agnostic towards its claims, neither accepting or dismissing them. We can acknowledge the values of disciplinary education in relation to practical skills and insights, while questioning how these are framed and used by institutions. It’s unwise to reject disciplinarity outright. Firstly, because that tends to encourage political and religious fundamentalisms. Secondly, because the dualistic thinking that reduces everything to an either/or choice belongs to the same binary thinking that’s embedded in disciplinarity itself. So we need to work in another space. One which the feminist thinker Geraldine Finn describes as: “the space between experience and expression, reality and representation, existence and essence: the concrete, fertile, pre-thematic and anarchic space where we actually live”.

As students on an Arts and Humanities Masters programme, you’re no doubt already navigating that space-between. So, I’m now going to touch on some of its paradoxes and possibilities.

In Anthropology and/as Education, Tim Ingold argues that there’s more to education than teaching and learning, and more to anthropology than making studies of other people’s lives. Instead, he sees both activities as ways of leading a life of study with others; that is, of attending to the world so as to open up paths of growth and discovery. I read this to be a variation on Isabelle Stengers’: “dangerous art of animating in order to be animated”. (I’ll come back to the danger involved later). Ingold goes on to argue for an education that’s direct, practical, an observational engagement, rather than the top-down transmission of knowledge by disciplinary experts.

That’s fine in principle, but the core issue for artists is that disciplinary art discourse doesn’t just determine what is recognised as art.

More fundamentally, it also assumes that imagination and creativity is exclusive to, and owned by, specialist groups or individuals – an assumption enshrined in copyright and patent law. This same assumption is part of the underpinning of the Western culture of possessive individualism – a culture and society that places the sovereign individual before the community. And its particular notions of personhood, nature and society have proved toxic. It’s vital, then, that we now acknowledge alternative understandings. For example, back in 1989 the psychologist Edward Sampson pointed out that: “there are no subjects who can be apart from the world; persons are constituted in and through their attachments, connections and relationships”. More recently, the physicist-philosopher Karen Barad has again reminded us that our existence is not an individual affair, since neither individuals nor ideas pre-exist their interactions. These understandings contradict the most fundamental presuppositions of both disciplinarity and possessive individualism.

So, if personhood, ideas and imagination emerge through our entangled intra-relatedness, we need to think in terms of how people, practices, ideas and materials interact as mutually co-constituting entities. I going to suggest the notion of “ensemble practices” as providing one way for artists to start thinking about this.

The term ensemble is usually applied to groups of musicians whose music-making depends on the relationship between individual skill and collective interaction. But each musician is themselves also an ensemble, a being who must attend to and coordinate what is remembered or read as sheet music, sensed, and physically played. That coordination requires attention– a combination of sympathetic curiosity, sensitivity, and openness. Attention is central to all creative work – whether we’re performing music, having a conversation, or making a banner – and we learn it through practical interactions in all sorts of ways and contexts, as Ingold suggests. The agnosticism towards disciplinary discourse I’m proposing allows us to maintain a necessary creative tension. Between this vital attention and the ways in which the results of art practices are conceptualised by specialist discourse.

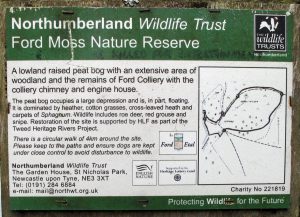

This brings me to a fundamental paradox. It’s disciplinary art discourse that’s brought you to this MA. But in the process that same discourse has gradually reframed your imaginative and affective relationships with the world. Disciplinary education requires both that you learn skills and that you internalise values via a specialist discursive language. Through the process hinted at in this slide, a relational animation– in this example evoked by a sand-painting ritual – is subjected to rationalisation and re-conceptualised as ‘making art’. In this way our initial desire for emersion in protean forces and materials is formalised into a highly specific disciplinary practice that, in Western culture, is subject to the specialist analysis and judgement that isolate art as a specific, discrete discipline.

The process of art education is, then, double-edged. It allows us to develop and maintain a creative practice, but it’s also a process of indoctrination into disciplinary values. If we simply internalize those disciplinary values, rather than remaining agnostic towards them, we risk conforming to a reductive orthodoxy. We risk that orthodoxy starting to dictate both what we feel able to make and what we feel able to say about what we make. When that happens, our sense of ourselves as open beings – as always being both more and less than the categories that name and define us – is repressed or lost. We then subject ourselves to the requirements of the disciplinary category “art” rather than engage creatively with the multiple relationalities of our worlds. This process of enculturation eventually results in art that simply illustrates some current aspect of art discourse.

A report published in 2015 – Humanities for the Environment: A Manifesto for Research and Action– can help clarify what’s needed. The report makes it very clear that the understandings our society now needs involve employing multiple, even contradictory,perspectives, something that’s alien to the logic of disciplinary thinking. Additionally, it stresses that we need to move beyond models that assume that knowledge is produced exclusively within the academy. It argues that we must find alternative understandings that exceed disciplinarily thinking.

The academy’s reply to this type of criticism has been to promote the notion of trans- disciplinarity.

But the term “trans-disciplinarity” still assumes that the discipline is foundational. And at the level of institutionally-managed practices – of what actually happens on the ground – that’s exactly the problem. Trans-disciplinary projects still remain subject to the authority of a discipline-based system of funding, evaluation, governance and dissemination. So they are all-too-often a face-saving exercise for disciplinarity as the final arbiter of “real knowledge”. This prevents us from hearing what other forms of knowledge – in the case of the knowledge embodied in this dance, one that reaches back to before the last Ice Age – might say to us.

In a chapter called Rethinking the Conversation in Re-mapping Archaeology: Critical Perspectives, Alternative Mappings, Erin Kavanagh provides a helpful insight into the underlying problems of trans-disciplinarity. She sees it as a tricky exchange that’s usually heavily distorted by different discourses and the unequal status of the participants. As a poet, artist and mytho-archaeologist working on the margins of academia, she writes from experience . She knows, for example, that the potential of trans- disciplinary work is restricted by the fear most specialists experience when faced with an unfamiliar disciplinary discourse. A fear that comes from disciplines and professions treating their fields of expertise as exclusive domains – each with its own distinct culture, linguistic habits, and traditions – all to be jealouslydefended against outsiders. A fear that’s considerably reduced if we are agnostic to the territorial claims of all disciplines, including our own.

Erin points out that, if we want to be taken seriously by members of another discipline, we have to learn to speak their language well enough to understand how they think. For genuine conversations across disciplines to take place, both parties must not only become conceptually bi- or multi- lingual, they must be sympathetically curious about, and sensitive to, the other disciplines’ concerns. This is why genuine trans-disciplinary exchange is rare. But it’s also why genuine conversationscan un-discipline our practices.

The curator and art writer Monica Szewczyk argues that entering into a conversation, properly understood, makes the creation of worlds possible. When we take part in a genuine conversation we enter a space-between different worlds. But – and this is the crux of the matter – in doing that we also run a certain risk or, in Isabelle Stengers’ terms, face a certain danger. We risk our own subjective world being destabilised, perhaps even redefined, by fully engaging with someone else’s world.The danger is that we will be transformed. That’s to say, we risk becoming both more and less than whatever disciplinary category we identify with – for example, the category ‘artist’. However, as I’ve said, these transformative conversations are fairly rare.

What does what all this mean in practice? It means that it’s not possible to discuss Ffion Jones’ imaginative work productively as something distinct from, say, her living and working in a Welsh-language speaking hill farming community, as well as working as a performance artist, academic and researcher.Her work, like her life, is a complex conversation between different, sometimes antagonistic, worlds. To navigate those worlds requires sympathy, commitment, curiosity, and an underlying attention that’s oriented by trust rather than competition. And these conditions are rare in contemporary professional life – certainly in universities and the art world – where most professional exchanges are instrumental, strategic, or competitive.

People do, of course, learn to be conceptually bi- or multi- lingual, to make productive border crossings between disciplinary territories. But such crossings are demanding and generate a certain level of discomfort – of cognitive dissonance, paradox, and ambiguity. Most people prefer to embed themselves in a familiar disciplinary world, a profession, or a given identity. Some however choose, or come to accept, to become outliers, to work out on the edge of different disciplinary territories or professions and to regularly cross their borders. As a result, they develop undisciplined practices.

I’m now going to suggest why doing this is important.

In Artificial Hells: participatory art and the politics of spectatorship, Claire Bishop writes about what she calls ‘pedagogic art projects’. In the process she reveals the tension between Joseph Beuys’ undisciplined practice and her own disciplinary critique. During the 1970s, Beuys’ work became increasingly conversational, a relational exchange with others art, education, politics and environmental activism. However, Bishop chooses to frame this work as a prompt to: “examine our assumptions about both fields of operation – art and education – and to ponder the productive overlaps and incompatibilities that might arise from their experimental conjunction, with the consequence of perpetually reinventing both”. This re-framing is highly reductive. It reduces Beuys’ work to providing the critic with an opportunity for analyse of the categories of ‘art’, and ‘education’ and their relationship. Bishop thus treats Beuys’ work not as an open act of social engagement, but as simply another opportunity to exercise her own disciplinary skills. This disciplinary reductivism is indicative of a fundamental problem for creative practitioners.

Earlier this year Darby English, writing in the catalogue for the exhibition Outliers and American Vanguard Art, highlighted one of the basic presuppositionsof critical art discourse. He writes: “The often brutal character of modernist criticism is shown in its insistence on the primacy of external judges, which is another way to describe its tendency not to think of makers as the primary seers and knowers of their work. Vanguard criticism displaces the maker’s vision and knowledge in favour of its own rigorously cultivated awareness of how Art operates…”.

Such acts of displacement remain the stock-in-trade of critical art discourse.

Critical discourse frames the work of Eamon Colman through genre – as landscape painting – and through technique – as the product of a colourist who grinds his own pigments. Categorised as ‘landscape paintings’, these works are assumed to lack ‘engagement’, as current art criticism understands that term. However, Colman does not describe himself as a landscape painter but as someone whose work responds to “listening to other people’s stories and interpreting their dreams”.Hewalks. He thenreconstructs what he encounters from memory, before adding carefully-considered, evocative titles. He has also said that his work responses to the earth as: “a living being like you or I … an organism that breaths and communicates”. I suggest it would be more relevant and productive to explore his work in these terms than reduce it to normative categories like ‘landscape painting’ and ‘colourist’. But because current critical discourse presupposes that landscape painting is incapable of ‘engagement’, it neutralises Colman’s work in terms of larger cultural conversations. If you want to find thinking open to the contribution Colman’s art might make to such conversations, you need to turn to the writing of a sociologist, Ben Pitcher, rather than to disciplinary art discourse.

The disciplinary process of displacement I’ve indicated makes it hard for artists to present their work as constituted in and through their own particular attachments, connections and relationships. As a result, they’re increasingly creating their own framing narratives.

Raaswater belongs to a narrative set in motion by the South African painter, researcher and performer Hanien Conradie.The work shares its name with a now-abandoned farm that, in the 1940s and 1950s, grew grapes for export. Her mother grew up there. The farm was named after the raging waters of the Hartebees River, which ran through the property. As a child, Hanien loved her mother’s stories about Raaswater which, growing up as a child of suburbia, sounded like an earthy paradise. As an adult she took her mother to visit the farm, which her grandparents had been forced to sell, and which Hanien herself had never seen. When they got there, the river was silent and all the indigenous vegetation had gone. European farming methods have so radically destabilized the water ecology that the river is now dry for much of the year.

Shocked by this situation, Hanien salvaged some of the clay that had featured in her mother’s stories of playing by the river as a child. She took it into her studio and created a simple ritual that allowed the river’s water to re-sound, to run wild again. From that she gradually evoked a new story about Raaswater. The river became a space made up of what the geographer Doreen Massey refers to as “a simultaneity-of-stories-so-far”. Hanien’s story is about land ownership, loss of indigenous habitat, and the importance of mourning at the intersection of personal history and environmental irresponsibility. That story, along with the paintings and other works it accompanies, is part of Hanien’s MFA project, Spore. It evidences the way her conversation with an ancestral place transformed her art practice into an ensemble practice. One in which a range of arts skills interact with material from botany, ecology, law, psychology and philosophy,generating a complex, open-ended, multi-dimensional relationship of materials and narrative that is more than the sum of its parts. A telling relationship that’s irreducible to any one category or discipline.

There’s an important convergence between Doreen Massey’s understanding of space as a simultaneity of ‘stories-so-far’”, and notions of a relational self as an ongoing conversation. Gulammohammed Sheikh evokes this convergence in his major project: Kaavad: Travelling Shrine: Home. Sheikh is from a Muslim family in Gujarat, a state subject to extreme anti-Muslim violence over many years. He has long been committed to staging visual conversations between different, sometimes contradictory, stories-so-far across both space and time. This draws in part on his childhood in pre-Partition India, when the belief systems of different religious groups interacted peacefully within a heterogeneous popular culture. Consequently, much of his work can be said to counter attempts by an increasingly virulent Hindu nationalism to suppress cultural exchange in contemporary India.

In Kaavad Sheikh provides a new, expanded context for the richness of the popular heterogeneous culture of his childhood. A kaavad is a portable, folding, wooden shrine used by nomadic storytellers to reveal images of different gods, goddesses, saints, local heroes, and patrons as their narrative unfolds. For Sheikh, however, it serves as a secular device, as: ‘…a site for atonement for innocent victims of the senseless violence of our times… a motif of remembrance, of memory”. Through it he enfolds figures from radically different backgrounds and spiritual traditions – his mother, medieval Hindu and Sufi saints, an anonymous sweeper, the Chinese Buddhist scholar Shoriken, St. Francis, Gandhi, and the prophet Mohammed – all within a complex, multifaceted, conversational space.

Sheikh imagines conversations between stories-so-far as a non-believer, but one deeply concerned about the failure of liberal, humanist cultural education in a fractious post-secular world. The results are complex relocations of old narrative themes within a new, cosmopolitan, multiverse, with the work’s many enfolding panels evoking a ‘safe space’ for debate.

Sheikh spent many years helping to create, and then defend, a secular educational space for Indian art students. However, in 1992 he was expelled from his academic post due to political pressure. I see Sheikh as having an ensemble practice that draws on, and works out of, a variety of distinct skills and understandings –those associated withhis roles as painter, poet, secular participant in Muslim culture, educator, activist, editor and cultural observer. Activities that then feed into his polyvocal conversation about heterogeneity and tolerance.

In 2007 Deirdre O’Mahony initiated the X-PO project. Her aim was to convert the decommissioned Kilnaboy post office in County Clareinto a centre for artistic and community activity in that small rural community in the west of Ireland. Local people embraced the project through its first exhibition: a tribute to the last postmaster, Mattie Rynne. This was followed by exhibitions, talks and presentations dealing with changes in the environment, in farm life, and in rural social circumstances – all mirroring events and concerns across the west of Ireland. Local interest groups later took ownership of X-PO through local history and mapping projects, using digital resources to create a community archive, and through using it as a meeting place. However, it continues to feed into O’Mahony’s SPUD project.

SPUD draws on education, activism, research, art practice and agronomy. It stages a conversation between elements of traditional local agricultural knowledge, self-sufficiency practices, and the relationships between agriculture and identity, by re-imagining Land Art as ‘Useful-Art’. It has involved collaborations withthe community of Kilnaboy,a South American research institute focused on developing disease resistant potatoes, and the Loy Association – a nationwide Irish group dedicated to preserving viable traditional farming practices. Originally concerned to present a more nuanced understand of the potato’s role in Irish culture, SPUD developed into a public conversation about sustainability, food security, and vernacular cultivation knowledge. Its potato lazy-beds – at the bottom of this slide – are here displayed outside the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

SPUD requires O’Mahony and her co-workers to identify, acknowledge, and work with the possibilities and limitations of different discourses and understandings. It employs multiple, sometimes contradictory, perspectives to find ways of working productively both with and across differences. Concluding her chapter in the recent book Rurality Re-imagined, O’Mahony identifies SPUD as a micro-political process, one: “necessary to remind us that the skills of both head and hand are needed if we are to actively respond to the challenges facing humanity today”.

Luci Gorell Barnes’ ensemble practice highlights other aspects of un-disciplined practice. Her Cartographers of Compassion: community mapping of human kindness might be taken as a typical example of socially-engaged art practice. But to take it in isolation is to miss the complexity and richness of her practice. This draws onskills, interests and an ethics located at the intersections of education, participatory and personal arts practice, academic research, and community engagement. It’s also particularly involved – often through narrative mapping – with the specifics of the place where she lives.

Central to her ensemble practice is a concern with learning and a commitment to people who find themselves on the margins; particularly young children with learning difficulties and migrant and refugee women. The overarching aim of her work is: “to develop flexible and responsive processes that allow us to think imaginatively with each other”. She earns part of her living as a long-term artist-in-residence in a Nursery School and Children’s Centre; work that includes the Companion Planting project on an allotment linked to the school. However, her approach is not simply that of the conventional, discipline-based, local artist. Rather, she is an informed and plural subject playing many different creative roles in many different contexts.

In The Power of the Ooze Simon Read – who lives on a barge on the River Deben – suggests that our eco-social problems require: “a particular kind of strategy that our culture has yet to develop and promote”. This requirescontinuous improvisation, without a desire for perfection or a fear of failure. Read works as an artist, teaches at Middlesex University, and serves as an environmental designer, community mediator, and ecological activist. He’s been involved in various projects on and around the River Deben since 1997.

His numerous large map drawings are always a response to issues relating to management strategies for fluid and shifting environments. They both delineate specific and recognisable possible future landscapes, and act as tools for active meditation in debates about changing environmental conditions. He retrieves, cross-references, and synthesizes material from many different official sources to equip himself to join the complex environmental planning debates around environmental management. However, his ability to imagine a synthesis of the material he collects is very much a product of his art training.

Read’s work on the Falkenham Saltmarsh project – an exploration of the conditions and potential for salt marsh stabilisation – led to him planning and creating barriers designed to prevent its erosion. These manage tidal flow and encourage the controlled deposition of silt. The practical yet sculptural barriers are “soft engineered” from timber, brushwood, straw bales, and coir – a natural fibre extracted from the husk of coconuts. They’re specifically designed to degrade back into the marsh over time. Simon’s response to the challenges of environmental change includes publicly acknowledging our need to find nuanced and complex solutions. Solutions that necessarily acknowledge the cultural implications and dimensions of change involved in re-framing our collective understanding of land, ownership, responsibility, ‘home’, and belonging.

Most of the people I’ve referenced would conventionally be categorized as artists and have no quarrel with this. But if you talk to them about what they do, you quickly recognise that their work can’t be usefully categorised through a disciplinary or trans-disciplinary discourse. Each individual is an informed and plural subject who productively adopts different roles in different contexts; subjects who understand that both they and their practices are constituted in and through their multiple attachments, connections and relationships.

There’s nothing particularly new in what I’ve been saying. In Australia, the Anthropocene Transitions Project is working to increase understanding both of the Earth as a single socio-ecological system and of the cultural drivers that threaten it. It’s co-ordinator, Kenneth McLeod, insists that we can only meet that threat if: “we climb out of our disciplinary and professional silos, take off our institutional blinkers, and start exploring genuinely transformative change; … ask ourselves how can we step into the “space between” disciplines and cultures where new thinking and ways of knowing and acting in the world are possible; where new ways of understanding and valuing the Earth can emerge”.

For those who experience creative involvements as something more than a disciplined category of work, meeting McLeod’s challenge requires a conscious un-disciplining – perhaps the cultivation of an ensemble practice along the lines I’ve indicated.

Indicative bibliography

Karen Barad Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning.

Jane Bennett The Enchantment of Modern Life: attachments, crossings and ethics.

Claire Bishop Artificial Hells: participatory art and the politics of spectatorship.

Darby English ‘Modernism’s War on Terror’ in Lynne Cooke (ed.) Outliers and American Vanguard Art.

Geraldine Finn Why Althusser Killed His Wife: Essays on Discourse and Violence.

Tim Ingold Anthropology and/as Education.

Erin Kavanagh‘Rethinking the Conversation’ in Re-mapping Archaeology: Critical Perspectives, Alternative Mappings.

Humanities for the Environment: A Manifesto for Research and Action.

Kenneth McLeod, Learning to Think Like a Planet – http://www.ageoftransition.org/

Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell.

Monica Szewczyk ‘Art of Conversation, Part 1’ e-flux journal no 3.