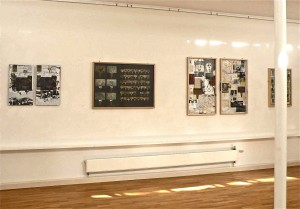

Terra Incognita: (all grass is flesh) – with (and for) Anna Boulton Biggs (2010)

This project is in one sense almost a ‘by-product’ of ongoing Debatable Lands work and its imagery shares a number of overlaps with that used in Between. In particular, the images enamelled onto copper plant labels.However, there is a particular emphasis on material gathered by my daughter Anna in the highly restricted area of Weardale and the dales local to it that she has been able to access over the last thirty plus years. As such, it engages directly with Anna’s endurance in the face of her illness.

In this respect the work relates quite closely to my earlier Hidden Wars piece, as reflected on in Debatable lands Volume II. The particular form of the piece – notably the use of enamel – was also in part determined by my on-going dialogue with the international enamel artist Elizabeth Turrell and with other artist involved in the travelling Drawing, Permanence and Place exhibition.

Drawing, Permanence and Place: some introductory thoughts

This text is the Introduction to the catalogue Drawing, Permanence, and Place – Beate Gegenwart (ed) 2011, Wild Conversations Press – for the travelling exhibition of the same name. This included work by: Beate Gegenwart Dail Behennah, Elizabeth Turrell, Emma Moxey, Helen Carnac, Iain Biggs, Jessica Turrell, Jilly Morris, Roger Conlon and Susan Cross.

It must have been easy to overlook the resonances of mundane enamel objects that, for example, signed the Passages couverts de Paris of the Walter Benjamin’s famous Passagenwerk or Arcades Project, just as it is easy to forget the power of the type of vernacular back-of-envelop drawing that Marlene Creates’ exemplary 1988 project: The Distance Between Two Points is Measured in Memories, Labrador provides to signify relationships between memory, place and belonging. This thematic exhibition provides a group of artists – linked only be a shared interest in drawing and enamel – with an opportunity to reflect on a topic centre to the PLaCE Research Centre’s concerns – namely the increasingly vexed understanding of relationships between notions of permanence (whether physical or in memory) and of place.

In this context drawing is taken as central – an activity that usually leads to a more or less permanent trace – an etching, a map, a topographical sketch, another, more elaborated, work of art. Like a whole category of vernacular enamel objects – street name signs, house numbers, commemorative public plaques, permanent notices and labels (everything from garden plant markers and industrial workshop safety labels to the small enamel signs designed to be hung on decanters and storage jars) – drawing too has implications for how we identity, differentiate and regulate our sense of place and the routes between places, thus of belonging and understandings of regularity and permanence. Consequently to employ the practices of drawing and enameling together is almost inevitably to raises questions about the relationship of action and trace in relation to belonging, memory and identity – whether these are bound up with mundane, almost subliminal, information or with the more subtle discriminations present in drawing.

Both drawings and vernacular enamel objects may “speak” of how we are expected to perform in, and respond to, all types of spaces in use on a daily basis. Both can make a significant contribution to the conceptual “mapping” and “naming” (in the widest sense) of the various spaces and places in which our human identities are formed and reformed and in which we encounter, accept or resist complex networks of social expectation and control. Their relative permanence (and the signs of their passage through time) is central to their social function, a powerful reminder both of the inscription of power in cultural objects and, equally, of our desire for some degree of stability and permanence based on shared and consensual social or domestic authority, however compromised this may be in the living.

The idea for this exhibition initially arose from a shared interest in drawing and the enameled object, but then became more specifically concerned with place and permanence. We accepted from the start that creative processes do not readily conform to pre-existing agendas, and that the intentions indicated here where only the starting-point for a visual conversation between bodies of work, one into which we hope to draw the viewer.

‘Terra Incognita’ (all grass is flesh) – with (and for) Anna Boulton Biggs (2010)

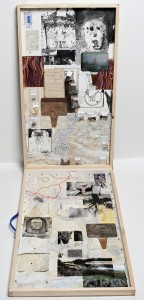

Since 1999 I have increasingly been involved in various forms of deep mapping – that is in “a blurred genre … or a science/fiction, a mixture of narration and scientific practices, an integrated approach” (Pearson & Shanks 2001) – that, in my case, engages with the intersection of memory, place and identity. These ‘slow art’ projects usually take a number of years and result in artist’s bookworks, often in series, or in time- based work. However I was originally educated as a painter and printmaker and periodically feel a need to return to making simpler, wall and/or floor-based work. Returning to my roots in the crafts of making allows me to ground my thinking in the down-to-earth alchemy of directly manipulating physical materials. (The basic processes involved, walking, gathering, sorting, cutting, sticking, coating, cooking, constructing and so on are, after all, also part of the store of common skills that still underpin our lives – no matter how digitally inflected these may now be – and the material culture that sustains them).

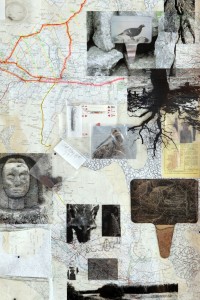

Terra Incognita (all grass is flesh) is an extended five-part ‘drawing’, the first half a projected deep mapping of my daughter’s life-world and made with her help. Her physical environment is restricted to two small but intensely known places, since she has suffered from the seriously debilitating physical illness Myalgic Encephalitis for over twenty years. However her restricted sense of physical place is constantly extended by a deep curiosity, often pursued through her interests in family history, photography and ornithology. These, together with my own reflections and the places to which they relate, formed the starting-point for this work.

It happens that the place with which the work is concerned is one that I “married into”, home territory to my wife’s maternal ancestors over many generations and a place we have returned regularly throughout our life together but which my daughter will shortly no longer be able to visit due to her illness. This situation provoked reflection on notions of place, permanence and what those terms might mean now that we must find an ecological ethics “after monotheism”. (My reversal of the Biblical phrase ‘all flesh is grass’ can be taken in this context).

It may seem odd to refer to this work as a ‘drawing’. However the term is accurate enough if taken as a verb. The act of drawing can imply a ‘drawing up or down’ of material into the peripheries of space or vision, a ‘drawing out’ of meanings or resonances otherwise too compressed to register, a ‘drawing together’ of apparently disparate elements into a particular constellation, a ‘drawing through’ as of a thread in weaving, and so on.

Drawing as act in these senses is the basis of my larger practice as a teacher/artist/researcher. One particularly appropriate to anyone interested in the methodologies of deep mapping as these can imaginatively serve to give us a better understanding of the complex reciprocities that, ecologically and socially, govern our lives. Reciprocities that, when properly recognized, require that we cultivate a rigorous disciplinary agnosticism if we wish to remain open to the multiple networks of connectivity of which we are a part.

This work reflects a long process through which an engagement with a place results in my making particular physical artefacts that are then taken back into that place and photographed in various ways. The whole conglomeration of resulting material is then assembled, edited and reassembled in various ways. I like to use a wide variety of processes as much for their various resonances as part of the material life of our day-to-day vernacular culture as for their particularities as craft practices.

I use the process of enamelling for a variety of reasons. Primarily because it involves the chance happenstances of firing, can be applied to everyday objects, and allows for a degree of erasure through the process of stoning back. Also because I like to sidestep demarcations between the “visual” and “applied” arts, frequently used to reinforce forms of exclusivity that have far more to do with reinforcing the cult of possessive individualism than with conceptual or aesthetic value. Finally, because I have been very fortunate in being able to work under the tutorage of Elizabeth Turrell, an internationally renowned enamel artist, who has been a constant source of encouragement and inspiration in suggesting ways in which this process might feed into my wider practice and concerns.