London

I was excited about being called for interview, but nervous about what would happen if I actually got a place and had to live in London. I wanted to believe my Foundation tutors, who had told me my work, ‘the broken necklace of a teenage troll girl’ as Dad once affectionately described one piece, would get me a place. I knew I had always worked really hard and, much to my own astonishment, also managed to overcome the innumerable logistic problems of attending a Foundation Course. At home I felt I’d earned my cofidence and was prepared for anything. But my old nervousness returned with a vengence when I was faced by the jostling crowds on the Tube and the sophisticated second-year students who directing us to wait to be called to interview and ticking me off on a list. I felt like a heffer in a holding pen.

I’d been waiting about twenty minutes when the only other girl in the room came over and whispered that, since obviously we weren’t going to get interviewed before the coffee break, maybe we should retreat to the loo and take stock? Suzie, who looked vaguely Chinese to me but spoke with an Irish accent, was clearly working as hard to hide her nerves as I was. We reassured each other and then shared her bright red ‘lippy’ to boost our morale. (Later my aunt told me I looked like ‘a tart’, much to my secret delight). With that simple act of sharing Suzie and I became two young women against the male art world. We agree to meet after our interviews and compare notes. Mine went by in an anxious blur and afterwards I found myself laughing about it with my new friend. I’d never met anyone remotely like Suzie. My wry account of the interview made her laugh so much that, as she proceeded to tell half the canteen, she ‘nearly pee-ed herself’. I quickly realised I must be as much a pleasing novelty to her as she was to me. Before she went for her train we promised to stay in touch whatever happened.

To tackle my fear of London I stayed an extra night with Aunt Claire. Armed with an ‘A to Z’ I set out to explore and discovered Foyles and the second-hand bookshops off the Tottenham Court Road. There I found a copy of Hamish Fulton’s‘Pilgrims’ Way’, which I took as an omen that, if I was granted a life here, it would not just be possible but might even be enjoyable, despite all I would have to give up.

Top Road, January (sketch)

Under snow the quality of sound changes up in the high hills. This has less to do with changes to the acoustics of the physical landscape than with the practical conditions regarding clothing imposed on anybody who ventures out in these conditions.

Walking the top road today all the usual early spring sounds are muffled, truncated, by the clothing necessary to function at over three hundred meters above sea level. Today a violent north wind intermittently blew snow horizontally across the land. All the usual taken-for-granted differentiations and qualities by which I navigate were subject to a single overwhelming distinction: in or out of the wind.

I needed two layers of headgear for warmth and dryness and that produced a new soundscape, one dominated by the scratchings and rustlings of woolen cap moving against waterproof hood, the rhythmical thump of boots on wet road that seems to travel up through the body itself; and the squeak and scrunch of wet snow, occasional bird cries, distant vehicles.

All these present themselves as filtered and limited by the degree to which I turn to face, as a satellite dish might, the source of the sound. This baffling or muting of all sound serves to synchronize hearing and line of sight, so that to be able to stand bareheaded out of the wind is to be returned to a three-dimensional world, to once again become the center of a circle of sound.

Mario

Mario, an Italian student at the art college who was some years older than me, befriended me almost as soon as I arrived. By the end of the autumn term I’d rather fallen for him. It wasn’t reciprocated, but it took me months to fully accept that fact. Mario was kind, funny, and knowledgable. He introduced me to his beautiful cousin Desideria, a design student, who in turn introduced me to their wide circle of European friends, most of whom were students studying Social Science subjects. Mario was warm-hearted and tactile in what I came to see was the usual Italian way, something I chose to misintrerpret for desire held in check. When, in due course, it dawned on me that he really wasn’t going to make any attempt to move things on between us, I felt lost and confused. I had long since worked out that my attempt to seduce Hamish had simply scared him off and wasn’t about to make the same mistake again. I became increasingly miserable.

Then, just before start of the the summer term, Mario sent me a rather sweetly-worded invitation to his twenty-fifth birthday party. We met as agreed. He complemented me on my dress as we walked into the club that his friends had hired for the evening and seemed genuinely pleased to have me on his arm. I tried to believe that, after all, this was the night I’d been waiting for. He danced with me to start with, but then increasingly left me at our table while he chatted to old friends or greeted acquaintrances; all with the clear expection that I’d follow his progress and smile when he pointed me out. Suddenly I felt beside myself with anger, fetched my coat, and left.

On Tuesday morning the following week someone told me they’d seen Maro put all his work into a van and leave. On Thursday Desideria met me as I arrived at college. She said Mario had gone to New York, that his uncle had asked to see me to explain, and that I simply must go. Bemused I agreed and taxi was duely sent for me. The meeting was, to say the least, bewildering. The moment I walked into his office Mario’s uncle, a diplomate of some sort, started talking, fast and in rather stilted English. He told me about the standing of Mario’s family; that he thought Mario a talented artist and a fine young man, despite his politics. (Which puzzled me since, unlike most of our circle, Mario showed scant interest in politics.) I was told Mario’s circumstances had changed, that he had moved to New York. I was assured his family were as upset by this as I must be; that they had been very much looking forward to meeting me in the summer. (I grew increasingly astonished. Mario had never talked about his parents to me, let alone about us all meeting.) Then Mario’s uncle got up, thanked me for ‘our conversation’, gave me a little nod, and showed me firmly out. I had had no chance to say much more that ‘hello’.

Desideria was waiting for me when I got back. When I told her how the meeting had gone, she was furious.

‘Basta, they said he’d tell you.’

‘Tell me what?’

Desideria was on the edge of tears but insisted she had promised Mario’s parents to say nothing. It was not her place. Eventually she relented a little, telling me Mario had inherited a lot of money when he turned twenty-five and had used it to go to New York. Pressed, she then admitted he’d apparently told his parents he wanted to get engaged to a beautiful Catholic girl called Flora. They had been to come to London in July to meet me. Later she discovered he’d also told some of his male friends we were sleeping together. I was speechless. The only other response I got to all my other questions was a derisive snort when I asked her about Mario’s politics. About ten days later she came to find me at lunch-time and handed me an envelope. It contained a letter of from Mario’s parents and a cheque for five hundred pounds.

The letter acknowledged that Mario’s behaviour must have been very hurtful to me and my family and asked that I accept the family’s profound apologies. The enclosed cheque was a testament to their regret and distress over what had happened. It was all very formal and felt vaguely threatening. Desideria asking me to sign a receipt to acknowledge that I’d received both letter and cheque. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I said I couldn’t take money from the family of a man who I fancied but didn’t fancy me, who’d told his parents he wanted to marry me and his friends we were sleeping together. It was just crazy.

Desideria managed a nervous laugh, but insisted I sign the receipt. I didn’t understand. It was a question of honour. They were genuinely worried about how my family might react. In Italy to talk about getting engaged was a very serious business. She assured me they were good people who, by their own lights, where trying to do the right thing, and so on.

In the end, I signed.

I swore I’d avoid entanglements with men until I’d graduated. Not knowing to which, or how many, people Mario had spoken about us before vanishing, I saw less of our mutual friends. Then, towards the end of my final year, I started going out with Quentin, a painting tutor, and became part of a crowd of postgraduates and younger staff. This included a beautiful young Irishman who, Suzie told me, was her head of department’s lover. After a while I noticed that he had ‘adopted’ one girl in the group in much the way that Mario had me. It finally dawned on me how naïve I’d been. When I next saw Desideria I asked her straight out if Mario was a homosexual. There was a long pause before she answered ‘yes’. She insisted that she’d not been able to tell me before because, when his family discovered he’d gone to New York with a boyfriend, they had made her solemnly promise to say nothing to anyone about it, particularly not to me. I felt foolish, angry and relieved in equal parts.

Later the money they’d insisted I take would enable me to set up my workshop.

Years later Desideria and I met up again and, over a long morning drinking coffee in the William Morris room of the V&A café, she told me what happened to Mario in New York. (Also about her own complicated personal situation during our student days. But that’s her story). Mario, it seems, had become a rising star of the New York art world before he died of AIDS, abandoned by his former lover and the group of artists he’d been associated with. They had discovered that after he’d left London, a student on the edge of our group had been arrested and deported back to Italy. Press articles had suggested this man had been involved with left-wing extremist groups and had been blackmailing various people to raise money. His friends believed Mario had been implicated in this man’s arrest and broke off all contact.

I simply didn’t know what to say.

In the park (sketch)

I walk between the trees and up the hill early, through green dappled sunlight and shadow and out into the open parkland. The cool air and sun both bath my face. There is a moment of intense closeness to him, but not as something separate from my walking up and out into this space where the grass has started to brown in the summer heat. I breath him in with the cool air and, with it, a sudden understanding that, whatever happens, it will always unite us. And then an overwhelming sense of tenderness followed by desire so sudden I stop and lean my back against a tree.

While he slept, his hair rumpled and his body sprawled across the chaos of the bed, I remembered climbing the orange-red sandstone that dominating everything on that distant childhood day, its colour so much stronger even than the miraculous blues of sky and sea. I remembered its heat on my sides and stomach, chest, neck and face as I twisted and turned, slippery with sweat from the effort of my climbing. The texture of the coarse-grained sandstone under my fingers, its weathered little ridges and shelves, the harder bands sometimes stained with traces of iron. All this texture hospitably available to my fingers and toes. And I had found my way up, much as I had just found my way with his body the previous night, our shared heat filling the feral darkness of his tiny basement flat.

My body held me completely and at no point did I start to think during that whole long climb; a self-contained organism that happily edging its way up until it found a place where heat and cooling breeze met in perfect balance, the summit its own natural climax.

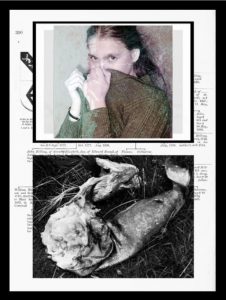

[1]The young woman at the top of this image is Flora and I would guess it was probably taken when she was living in London.