Like any university teacher, I learned early on to exploit the performative aspects of lecturing so as to hold the attention of students. In 2007 I worked with a type of performative intervention as part of visits to particular sites, including Temple Meads station in Bristol and the military training ground at Mynydd Epynt. This involved the placing and photographing of small images and, at Mynydd Epyn, of three small lead objects at various points. These photographs were then used in various contexts – primarily books works and performed presentations.

In 2008 I began to extend this interest into performative presentations at conferences, where I would arrange for someone in the audience to speak part of the prepared text. In 2011 I worked with Mel Shearsmith, herself an experienced performer, to create the performance presentation All that keeps your memory from turning to ash in my mouth is… for Mapping Spectral Traces IV event, held in Maynooth and Dublin. This piece, which takes the Avon river as it flows through Bristol as its starting point, showed me new ways of thinking about and evoking material relating to the ecologies of environment, society and self. Mel and I continue to work on this piece in various ways, and we hope to perform an extended version of it again in the future.

MYNYDD EPYNT / SENNYBRIDGE

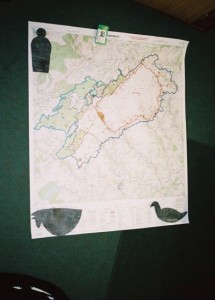

This section is based on work done as part of an AHRC-funded funded workshop, led by Mike Pearson and undertaken by members of the Living in a material world: A cross-disciplinary location-based enquiry into the performativity of emptiness network. My own work consisted of two parts. During the period of time we were at Mynydd Epynt I carried out a discrete intervention, material from which fed into various talks (including the one from which the side above is taken) and publications. After the event I used a map, photographs and notes to construct a work – Hidden Wars – that reflection both on the emptiness I had found at the site and on other forms of exile and emptiness.

Find a ‘way of telling’ about it which has personal and communal currency” (Mike Pearson 1998: 41)

It is not down on any map, true places never are.’ (Herman Melville, Moby Dick)

Now the site of a Ministry of Defence training site (SENTA), until 1940 this area was occupied by a community of farmers and their families. To create SENTA 54 homes were vacated and 219 people were obliged to leave. At the same time a primary school, a church, and the Drovers Arms inn were closed. See Herbert Hughes (1998). An Uprooted Community: A History of Epynt, Cardiff: Gomer Press.

Posted at May 02/2007 01:41PM: Angela Peccini: Jo and I have been talking about your practice in the way that the object pulls in attention – foregrounds the relationship between you and site – the performative act of marking, of placing the image – how that populates the frame while at the same time signals its previous emptiness. Rather than the ready-made, it’s the always making?

MYNYDDN EPYNT

First thoughts towards “telling” a story in words and images.

14/06/07 – Introduction.

In preparation for entering the “exclusion zone” that has re-placed “Mynydd Epynt” as once was, I felt I needed to take with me something that related to a world that had been slipping away long before it was excluded from that zone in 1940 – markers of an already fragile past and some kind of catalysts for memory and reflection. Although I did not know it at the time, what I wanted to mark was the mentality which named this upland area “the place of the horses”.

I did not know what to expect of our visit to the site, and I certainly had no wish to impose some superficial interpretation of my own on what is clearly a recent and painful episode in Welsh history. (I did, however, grow up around guns and the kind of men who like handling guns, and remember only too well a rifle fired directly over my head so that I would “know what it sounded like”). Having recently spent some time visiting and drawing in the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford, I made some small “catalytic” objects cut from sheet lead – a metal with an obvious and particular resonance in the environment that I was about to enter. These crude objects – made to be mounted on sticks that could double up as legs – were free adaptations of talismanic charms against evil that come from a number of different European folk cultures which share a common “Celtic” pre-history with Wales. They were also a way of acknowledging that, as an outsider and, at least in part, English, I felt uncomfortable about engaging with the specifics of the recent past in Wales, yet also sympathetic to the painful ambiguities and complex resonances of that place for those for whom that place has powerful and difficult cultural resonance.

There are three objects/markers, designed in part to echo the targets I anticipated might be found on the site, which I took there intending both that they might act prompts when I came to “tell” the place to others and, however odd this may seem, as “gifts” that could be left there. A secular offering to the official forgotten “spirit of place” that is clearly present both in the Welsh language and, in the form of the horses themselves, to what remains “near” to, but removed from, this now “emptied” site.

The images below are some of those that, for me, serve that function in relation to my own attempt to “tell” this place.

“Where in any other village there might be lawns or vegitable plots, there were areas of grass without any real sense of edge – none of those markers that allow the performance of semi-domestic outside space – grass that was well-trodden as if by hurrying children taking a short-cut to school. There are, of course, no children in this village, only young men and their older, more experienced officers. A school of sorts”.

“There were no fires in the fireplaces in the village, and no kitchens in which to cook food. There were only rooms as containers of so much space to be negotiated, lost or won”. (Mars leaves no place for Hestia).

“Elsewhere, beyond the village, there were the bullet-riddled remains of targets that had once sprang up out of the ground to challenge the advancing solders, to put them through their paces. Now the quasi-bodies of the defeated enemy are left to rot in the rain ….”

“… and the baby bunkers, the underground safe-havens where the targets had once been hidden ready to challenge the soldiers, are now empty”

“The rotting, riddled targets, left alongside these little grave-like bunkers from which they had once sprung, made me think of the impossibility of any kind of passive hiding out in this landscape. I begin to feel that here the only real possibility of safety lay in adopting the particular drive to fight every inch of the ground so as to preserve yourself, to ensure your own survival. That’s what the soldiers go there to learn. (I have a taste of that atavistic and compelling drive from going out to cull deer with my father as a child). I learned at Epynt that safety for the soldier is derived from subjecting his body to the absolute demands of the land as a sheltering means of survival when under fire – adapting to performing a warscape where your only chance is to keep low, keep moving, watch your step, watch your back, act quickly, instinctively and without any distracting thought that might take your attention from the task in hand. To use the land to take maximum advantage of the cover provided and keep maximum vigilance against what it may hide. It is to attack, with the maximum of effective force, whatever is put in your path and to push through it. Only such an instictive sense of the doubleness of the land – as shelter from and for your enemy – will ensure there is a way out alive. All this seems to depend on internalizing the supposition that your every move has the potential to give you away, to subject you to a deadly gaze, so that your every step must be determined by an instinctive logic that, when this warscape is performed in earnest, is the highly mobile, deadly, equivalent to the way in which hill sheep survive by becoming ‘hefted to the hill'”.

“And yet perhaps the strangest, most uncanny aspect of the whole military exclusion zone is that what is normally the most lethal area within it is, when we visit, seemingly the most empty, the least obviously disturbed by what is performed there”.

“Perhaps, in the last analysis, what is most powerful in that place is the sense of an apparent emptiness shaped to the will of an invisible power, one that has in turn rendered invisible the animate qualities from which this place originally derived its name”.

Afterthought

Perhaps all travellers’ tales, to be worthwhile, have in some way to be performed on a number of levels? Childhood memories and their landscapes had primed me in advance, almost without my conscious knowledge, to concoct the means to create a little ritual. I had a plan to smuggle in my crude markers of otherness as “protection” against what I had intuited would be, on a personal level and perhaps on other levels as well, something of a toxic resonances in this military place. Arguably a certain toxic emptiness resonant with the sixty years of lead pumped into the Impact Zone. If that somewhat childish “protective ritual” had to have accompanying words, they would go something like: ‘lead for lead, dust to dust, ashes to ashes’. That is, they would try to evoke another sort of emptying out. One that might make it possible to let go of the memories and fears that this militant, single-minded, indeed almost fundamentalist, place (as it is now) brings to mind – fears that have a real, contemporary, and political dimension (one resonant in every newspaper, in every news cast, and to which the historical dimension of Welsh eviction adds considerable weight), as well as being childhood ghosts – make possible another emptiness in which I can wholeheartedly and simply hear the skylarks. The desire that animates that wish to listen to the natural life of the place is not, at least in my view, nostalgia or some kind of “escape” into nature. it is one way back, against the grain of time, towards a necessarily limited empathy with what has been lost by others. I speak no Welsh, and I most certainly cannot speak with the dead, but that does not prevent me hearing, in the emptiness of the Welsh sky, the song of Welsh skylarks. And I can believe, without pretention, that I hear those skylarks as former inhabitants of these hills and valleys would once have heard them. And, indeed, as a soldier, pausing between exercises today, may still catch their sound. Any evocation, even a secular one, is after all an attempt to perform a little necessary magic in the world!

“Hidden Wars”

1). Mynydd Epynt / Sennybridge

Dear Anna I was staying in Mynydd Epynt between 25-27 May 2007, working with a diverse group of people (mostly academics) to prepare to give an account of the various kinds of “emptiness” that the site manifests. One of the greatest ironies of that place is that, since the military acquired it on 30 June 1940, it’s been untouched by development or agricultural improvement. Nothing has happened other than the creation of a fake “village” in which soldiers are trained in street and house combat and the gradual accumulation of the inevitable detritus of war – spent mortar shells, burnt out military vehicles,vast quantities of metal buried in the Impact area, and so on. So the Bronze Age boundary banks and deep-cut medieval tracks are much as they would have been for the original Welsh (and Welsh-speaking) community expelled from the mountain in the early stages of the Second World War.

All of this – along with a whole lot of stuff in my own past re-activated by being in a landscape devoted to disciplining the hunted/hunting body in particular ways – totally preoccupied me when I was at the site and for some months afterwards. Only as I worked on developing the documentation of the project of “witnessing” I had carried out, using little lead signs which now remain as close to the heart of the Impact Area as I could safely take them (lead signs of witnessing to join “lead” as euphemism for death – did another layer of absence start to appear to me.

That absence begins in the loss of the indigenous Welsh community from that mountain, from a landscape in many ways so like that in Weardale in which you used to play and around which we still drive together when you’re well enough to get out. It began that way but then opened into my own sense of loss – my loss of your presence in the active landscape of my life, the loss of being able to actively share in all the sights and sounds that are so familiar in Weardale and so present by their absence at Mynydd Epynt. Thinking about the children in the old school and the horses of Mynydd Epynt (‘place of the horses’) took me back to before you were ill, to your half-joking, half serious cry of “Want a pony”!

So I made a list of all the things I’d have liked to see and hear there with you – in “the place of the horses” – but can’t. I made a list and I placed them in spirit back into that world as mapped both before and after the war came. It goes as follows:

1. Large pile of stones

2. Sudden rain

3. Sound of running water

4. Deep cut track

5. Smell of wood smoke

6. Small birds fly away

7. Child’s woollen hat hung on a branch

8. Beer cans 9. Stray cow

10. Boy with a large stick

11. Moth caught in a spider’s web

12. North wind

13. Old shoe

14. Man and woman in parked van

15. Sound of distant chain saw

16. Sweet rappers pushed into a hole in a rock

17. Cold, wet Sunday afternoon

18. Small girl with a large sheepdog

19. Roe doe

20. Burnt wood from an old fire

21. Two women walking and laughing

22. Waves of grass catching the light

23. Man out running in the rain

24. Dead sheep

25. Children’s voices in a wood

26. Fag-ends in a puddle

27. Owl in a tree

28. Sound of a generator

29. Woman on a horse

30. Cloud over the sun

31. Man singing while he works

32. Wind in the trees

33. Black dog alone on the road

Like you, the horses are still in exile, are not in their proper place.

With all my love,

Dad

2. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – a hidden war.

On the 16th June 2006 Eileen Marshall and Margaret Williams published a detailed report – (http://www.ahummingbirdsguide.com/wmarwillinquest.htm) – in which they reflect on the Brighton Coroner’s inquest into the death of 32 year-old Sophia Mirza. Ms Mirza, although seriously ill with medically diagnosed Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), had been wrongly sectioned under the mental Health Act before she died.

The circumstances leading to Ms Mirza’s death were recorded by her mother Criona Wilson as follows:

“In July, the professionals returned – as promised by the psychiatrist. The police smashed down the door and Sophia was taken to a locked room within a locked ward of the local mental hospital. Despite the fact that she was bed-bound, she reported that she did not receive even basic nursing care, her temperature, pulse and blood pressure (which had been 80/60), were never taken. Sophia told me that her bed was never made, that she was never washed, her pressure areas were never attended to and her room and bathroom were not cleaned.”

As the Coroner’s report makes absolutely clear, Sophia Mirza died because she was suffering from ME. To be more specific, her death from ME/CFS was in part caused by her illness, in part by the fact that she was denied medical intervention and in part, no doubt, by the fact that she forcibly removed from her home and locked up in a psychiatric ward did not help her physical and mental wellbeing. This death might appear to be a tragic accident due, say, to a wrong diagnosis or a genuine misunderstanding. In fact nothing could be further from the true. Sophie Mirza died because of the calculated actions of official bodies acting in open defiance of World Health Organisation’s formally classification of ME as an organic disease of the central nervous system in 1969 with the code G.93.3 and the 1978 symposium of the Royal Society of Medicine at which ME was accepted as a distinct entity.

ME patients and those that care for them are increasingly resisting the official policy being developed to address ME – a policy directly executed in Sophie Mirza’s case – and based on attempts to reclassify a medical condition as a psychiatric problem. As Marshall and Williams testify, this policy has and is resulting in the psychiatric abuse of ME patients, aided and abetted by what they rightly refer to as “medical arrogance and ignorance”. The result of this policy is that ME patients are being ’treated’ by people who are happy to submit their patients to extremes of physical and mental anguish in order to further their own careers. This is possible because it is “financially and politically convenient and profitable” to act in this way “on behalf of a number of extremely powerful corporations and government departments”. (See http://www.ahummingbirdsguide.com/whatisme.htm).

It is against these corporations and government departments that those who care for ME/CFS patients are fighting. In the UK they are effectively faced with a systematic, state-condoned, campaign of abuse and cruelty towards those who suffer with ME. I know this because my daughter Anna has been suffering from ME for the last 18 years.

Bristol October 2007