[N.B. All the images are used with the permission of the person whose work is referred to].

Introduction

At the end of June I went to the west of Ireland to attend a conference – Landscape Values: Place and Praxis – organised by Tim Collins, Gesche Kindermann, Conor Newman and Nessa Cronin for the Centre for Landscape Studies at NUI, Galway. The conference was at NUI Galway because the university is a member of the UNISCAPE network, a Europe-wide group of universities concerned with landscape research, education, and the implementation of the European Landscape Convention. This gave the event its particular flavour and orientation. INSCAPE’s member institutions are drawn from across Europe, although universities in the UK and Germany are conspicuous by their absence. I’ll come back to the significance of all this later.

I have known Nessa for some time, originally through the Mapping Spectral Traces network and through a shared interest in deep mapping, and met Tim and Conor while I was working as a visiting researcher at NUI, Galway. Knowing them, I guessed this was likely to be an interesting and worthwhile event. Their thoughtfulness as individuals – and of Unescape as an organisation – was confirmed early on when all speakers were asked to submit written versions of their papers well ahead of the event itself. These appeared in a beautifully produced paperback book that was in our conference packs when we arrived. This enabling us to choose more productively which sessions we wanted to attend, without all the usual concern about missing altogether something vital by making the wrong choice on the basis of a short abstract.

What follows here is a personal reflection on the event as a whole although, I must admit, one filtered through my own interests in activities such as deep mapping. (Those unfamiliar with this cluster of practices might want to look at the Humanities Special Issue “Deep Mapping”, which can be downloaded for free and includes an article by Silvia Loeffler, whose work is referred to below).

Grounding empathetic imagination

I went to Galway two days early. I wanted to take the opportunity to catch up with my friend and former PhD student Dr Ciara Healy; also to meet with Nessa and Nuala Ni Fhlathuin – a doctoral student with whom we will be working (together with Deirdre O’Mahony). Arriving early also enabled me to unwind a bit before the event started.

Of the various presentations and events on the first day for myself the most memorable by far was the performance related to the Tim Robinson Archive: Artists in the Archive Project initiated by Nessa. This combined live music written by Tim Collins, choreography and dance by Ríonach Ní Néill, text, song, and a film by Deirdre O’Mahony. This performance provided a wonderful sensuously knowledgable counterpoint to the more general governance-oriented and other perspectives offered earlier in the day. As such it grounding my thinking back into the complexities of lived experience, lived traditions, and the tacit paradoxes that haunt the creation of the new Tim Robinson Archive, recently established in the James Hardiman Library at NUI, Galway, following his decision to return to London.

The second day of the conference extended that sense of grounding, with all conference attendees going out into the region on one of four carefully themed and structured field trips. Having an interest in bogs – practically through my friend Christine Baeumler and as archetypal psycho-geographical sites through James Hillman and others, I joined the trip to the turf bog at Lough Boora, which included a visit to Ballinsloe and the Shannon. Direct contact with several active members of the local community there, who are trying to work out a future in the face of the scaling-back of turf cutting, enabled us to get a clearer sense of the difficulties and opportunities that result from the implementation of environmental policy. In a small way it also gave us an opportunity to contribute ideas and information that might be of some use to the community.

The work that has been undertaken at Lough Boora is impressive and the dedication of those trying to construct an alternative future was as inspiring as it was humbling. The EU’s shift to restrict turf cutting on environmental grounds, still highly controversial in Ireland, has led to a great deal of innovative action by the community. My overall impression from our discussions was of their willingness to open themselves to new possibilities and of the pressing need for people in academia and the cultural sector (individuals with specialist knowledge) to listen, and try to try respond appropriately, to the needs of local communities hungry to find ways to save themselves from what is effectively social annihilation by decisions made elsewhere. Often with too little consideration as to how their impact ‘on the ground’ might be mediated and transformed into possibilities rather than what must often seem like a slow death sentence. That Conor Newman, who organised our trip, had clearly gone to some trouble to build a relationship with the group who met us was reflected in the warmth and appreciation they brought to our exchanges.

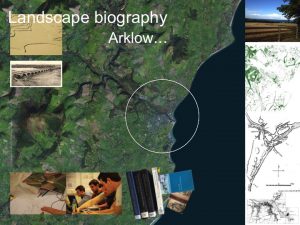

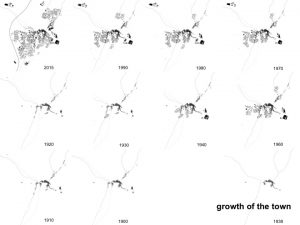

Following our visit three speakers presented in a small church in the afternoon. One was Patrick Devine-Wright (from Exeter University), whose presentation on Varieties of place attachments and community responses to energy infrastructures: a mixed method approach reinforced my earlier impressions and suggested ways in which the kind of alternative mappings that interest me might be deployed in such contexts. This set up interesting suppositions in relation to another of the presentation, by Sophia Meeres, on Infrastructural struggles: the making of modern Arklow, Ireland. This showed how architecture students working in a learning context can make use of deep mapping processes to plot a city as a changing taskscape, where the detailing of its infrastructure struggles over a two-hundred-year period become the basis of an analysis of the decisions that inform the space of a communal lifeworld.

Given the length of the conference and number of parallel sessions that I could (and could not) attend, it will be obvious that I can’t possibly comment even on those presentations I did attend. Consequently, I will concentrate on a few that particularly spoke to me in terms of my own interests – by Jacques Abelman, Aoife Kavanagh, Silvia Loeffler, Sophia Meeres (touched on above), and Eilis Ni Dhuill. (I deliberately did not go to sessions at which my friends Simon Read, Ciara Healy, Geared O hAllmhurrain, Harriet Taro and Judy Tucker and Karen Till and and Gerry Kearns presented, since I wanted to experience ideas from people I didn’t know. However their essays in the conference publication are well worth reading).

Jacques Abelman works as a landscape architect and is currently based in the Netherlands (but will move shortly to teach in the USA). His presentation – Cultivating the City: Infrastructureof Abundance in Urban Brazil – interested me both for its content and because it’s tenor seemed to me to reflect his broad education and experience. This took place in the USA, England and the Netherlands (his first degree is in environmental science with fine arts and philosophy), and he worked as an environmental artist, ecological builder, and garden designer before moving into sustainable design and landscape architecture. The presentation provided a succinct and intriguing introduction to his Urban L.A.C.E. / Renda da Mata project. (L.A.C.E. stands for Local Agroforestry, Collective Engagement, while Renda da Mata means “Forest Lace” in Portuguese), which I won’t try to outline or discuss here since it can be much better explored via his web site. However, what particularly impressed me was the way in which it built on sustained fieldwork on the ground – resulting in an impressive and well-grounded range and depth of knowledge. In a sense this project provides an exemplary model for the type of practically-oriented ‘deep’ approach to researching the basis for a socio-environmentally responsible landscape architecture of which I had a brief and tantalising taste when discussing deep mapping with landscape architect students and their teachers at Virginia Tech some years ago.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Jacques’ presentation raised a number of issues around landscape democracy and questions of de-professionalism (as underwritten by disciplinarily) and given the claim that ‘citizens do not operate within disciplines’. However during the exchange after the presentation I was somewhat rebuked by one audience member for apparently suggesting a ‘bottom up’ rather than ‘top-down’ model in relation to specialist/vernacular collaborations and issues of responsibility for the Commons. This led to a brief but fruitful exchange about the need to set aside supposedly ‘modernist’ and ‘authoritarian’ notions of the professional or specialist (which in my view are not restricted to the modern period but rather embedded in the culture of possessive individualism), towards notions of an ability to make authoritative specialist contributions to debate and action with regard to the Common Good. Here the example of Brexit might be seen as indicative of what happens when populist political views predicated on prejudice and outright lies gain the upper hand. Given Michael Gove’s now notorious execration of ‘experts’ this seemed a point well worth absorbing.

Aoife Kavanagh

Aoife Kavanagh is a professional musician (piano, violin, flute, and viola) and music teacher who is currently undertaking a PhD on music, place-making and artistic practice in the Geography Department at NUI, Maynooth. Her presentation – Making Music and Making Place: Mapping Musical Practice in Smaller Places – is based on the working premise that places, perhaps particularly in Ireland, may have a ‘musical ecology’ that extends well beyond performance by professional musicians and that understanding that ecology spatially, through ‘community deep mappings of of music and place’, can give a ‘voice to people in places to uncover and document that which might otherwise be overlooked’. In certain ways her approach seems to me to resonate quite closely with that employed by Luci Gorell Barns’ Cartographers of compassion: community mapping of human kindness project in Bristol, albeit in a different register. Interesting, she has built on Rebecca Krinke’s (2010) project Mapping of Joy and Pain, with it’s particular emotional focus, while adapting this approach as a way to collectively ‘map’ more nuanced and complicated ‘musical stories’. Of particular interest to me were Aoife’s comments on the challenges involved in this project, since these tend to reinforce my own views. Namely that a combination of positions – those of ‘insider’ (in her case the importance of being a musician/music teacher who understands the passions and limitations of the ‘lifeworld’ in which she is working) and ‘outsider’ (researcher/cartographically-oriented artist) – is a central aspect of this type of work. This first became clear to me in relation to Ffion Jones’ work in mid-Wales, which took her parents’ sheep farm – Cwmrhaiadr – as the focus of her PhD project. One in which this dual role was central to her concern with ‘woollying the boundaries’ between the world of upland sheep farming in Wales and academic understandings of rural life. This seems particularly important when the researcher is also embedded in the lifeworld of a particular community and so must act as a ‘bridge’ between worlds distinguished by emphasis on performativity on one hand and discourse on the other.

Silvia Loeffler

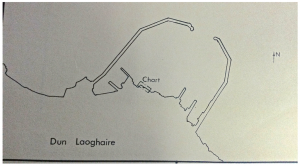

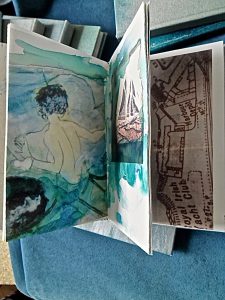

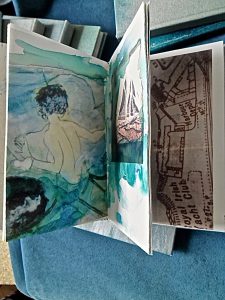

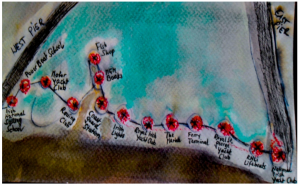

Silvia Loeffler is a post-doctoral researcher at NUI, Maynooth and currently holds an Irish Research Council Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellowship for her project Glas Journal, A Deep Mapping of Dún Laoghaire Harbour, which was the subject of her conference paper. She has also published an illuminating article on the project – Glas Journal: Deep Mappings of a Harbour or the Charting of Fragments, Traces and Possibilities .which I would recommend to readers interested in this area of work.

Taken together, these two texts provide a valuable record of the project and make a useful contribution to on-going discussions about this type of chronotopic mapping work. Although her title for the conference paper – Place Values – Glas Journal: A Deep Mapping of Dun Laoghaire Harbour (2014-2016) – uses the term ‘deep mapping’, she spoke of her work primarily in terms of both ‘liquid’ and ‘tender’ mappings (with the inevitable resonance of Giuliana Bruno’s discussion of Madaleine de Scullery’s Carte du pays de Tendre in her Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film).

This seems entirely appropriate for a ‘collaborative, multidisciplinary cartography project that explores the layered emotional geographies of Dún Laoghaire Harbour, Dublin, that focuses on ‘performatively mapping the intimate rituals and everyday performances of those individuals who live and work in the harbour’. In the abstract to the Humanities article, Silvia refers to the work as ‘a hybrid ethnographic project’ concerned with ‘the cultural mapping of spaces we intimately inhabit’. She adds that by developed the project with the participation of local inhabitants of Dún Laoghaire Harbour, the project is able to explore the maritime environment as a liminal space, one in which the character of buildings and the area’s economic implications ‘determine our relationship to space as much as our daily spatial rhythms and feelings of safety’.

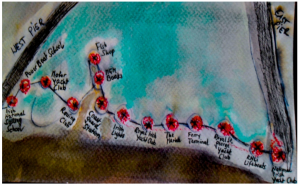

The project is as ambitious as it is complex. Currently Silvia is working with fourteen individuals who live and work in the harbour to produce handmade books that will constitute a record of ‘what the harbour space means to the residents based in the old coastguard station along with individuals involved with a host of other harbour related organisations and clubs. What seems to me particularly valuable about this project is summed up in relation to the richness and complexity of reference and evocation in Glas Journal Border Map (Sept. 2014) and other work illustrated above. She summarises ‘the interactions between human beings and their habitat’ as existing as: ‘a constant flux of appearance, disappearance and reappearance that may be compared to a tidal system regulating liquid states of times and places’. Given the preoccupation throughout the conference with issues of heritage this statement seems to me to evoke a powerful lesson that, in our often over-literal haste to preserve the past, we are still reluctant to take on board.

Sophia Meeres

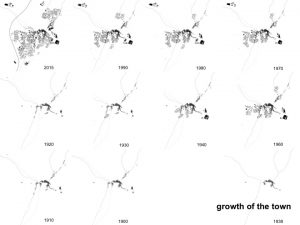

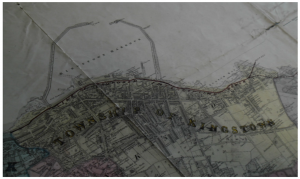

Sophia Meeres has taught in the School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Planning at University College, Dublin since 2004. As mentioned above, she gave a presentation entitled Infrastructural struggles: the making of modern Arklow, Ireland. This described a long-term collaborative project with her Masters students that relates directly to her teaching at UCD, which places an emphasis on ‘resilience, sustainable design and development’ and is taught within a multi-disciplinary context and a an ‘understanding of site-specific processes’ with a focus on research and analysis ‘seen as a creative act’. The overarching concern is ‘to help uncover local opportunities and potential for future directions’, something that spoke directly to the experience of speaking with the various individuals working to create a new understanding of Lough Boora and the communities linked to it. It is indicative that an earlier paper – A Biographical Approach to Understanding the Landscape (a contribution to the Landscape and Imagination. Towards a new baseline for education in a changing world ) – proposes a biographical approach to landscape that: ‘seeks to better understand local cultural conditions, issues and circumstances, disclosed through stake-holder participation and by other means, by linking present conditions to the past physical, social and economic “life” of a place and its people.’

The aim of such an approach is to better understand a place in ways I would see as aligning to both deep mapping and to Kenneth Frampton’s notion of Critical Regionalism in that it’s focus is on gaining: ‘greater and more detailed understanding of a settlement in its milieu’ with a view to articulating ‘development proposals that respond better to place’ Sophia believes – rightly in my view – that this “biographical approach” ‘has potential in terms of practice, research and landscape architectural education’, a belief that clearly animates the work she and her students have undertaken in relation to Arklow.

Eilís Ní Dhúill

Eilís Ní Dhúill is a polymath whose research interests include storytelling, folklore and film. She has a particular interest in the use of film to present Irish-language literature, drama and culture and has published in this area. She gave a presentation entitled: Sounds of the past in west Kerry: Creating, recalling and transmitting cultural values through place-names and associated narratives. I find it hard to give a clear account of this presentation because I became fascinated by resonances in what Eilís was saying as these might relate to my interest in the English/Scottish Borders region. Her focus on the way in which Irish place-names catalyse story-telling in west Kerry led me to ask her whether these stories were in any sense gendered – that is whether men and women told different stories about the same places. It appears that they do, a point I would link to the implications of different categories of Border ballads. That said, the nature of our conversation is probably too particular to my rather idiosyncratic interests in folk lore to be of general concern.

Afterthoughts

Although at one level I found the bulk of the conference very enjoyable and rewarding, I also have a strange feeling that the conference I experienced it was probably not that experienced by the majority of attendees. This may be due to the fact that we tended to fall into rather different categories with interests that, while they undoubtedly overlapped, may have had less in common in terms of framing and orientation than UNISCAPE may assume. My experience may also have be influenced by the fact that I live in a country utterly divided socially and politically, and not just over Europe. A country whose government’s austerity measures and social security reforms have, for example, just been the subject of a United Nation’s Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights report that confirms these are in breach of their obligations to human rights. This gives me continual pause for thought in relation to those whose power and authority is linked to forms of cultural and intellectual capital sanctioned by the status quo – including those who represent their institutions as part of bodies like UNISCAPE.

It is significant that just before the conference opened UNISCAPE held its General Assembly (the institutional equivalent to a business AGM), an fact that no doubt ensured that many attendees were senior academics representing member institutions. In short, UNISCAPE is deeply enmeshed in the realpolitik of a resilient neo-liberal status quo and these senior academics are members of an elite that can expect to engage directly with effecting issues of planning and governance. They also appeared to be for the most part from Social Science disciplines and landscape architecture practices. They and their proteges were also the keynote conference speakers. A second, more diverse contingency was made up of people with a background in the visual arts or music and an interest in ecological and landscape issues, including those related to environmental and heritage governance. A third group crossed between these two categories, many of them landscape architects with a practical interest in the uses of creative fieldwork.

It seems to me that what the first group have in common is a professional interest in landscape research, education, and the implementation of the European Landscape Convention through reform and governance relating to landscape planning and heritage. However, my underlying sense of this interest is that it is heavily framed by a detached/’objective’ thinking about landscape (including place as heritage), rather than direct emersion in specific places as an active constituent of their own particular lifeworld. As such their interests often seemed to lack either the psycho-cultural dimensions of what James Hillman calls the ‘thought of the heart’ or the empathetic imagination that, as Paul Ricoeur reminds us, is necessary to any effective political mediation. (And this at a time when the authority and ‘objectivity’ of science – for example as practiced in the medical field in the UK – has been shown to be utterly degraded, simply a debased ‘post-factual’ science in thrall to our debased ‘post-factual’ politics).

So I sometimes had the sense that individuals in these two different groups were, often without realising it, quite simply talking past each other. There was very little transformative conversation as I understand it. This may, of course, be largely a reflection of my own prejudgements and bias. That said I sensed that, for the first group, the second were in the last analysis an irrelevance, except in so far as they enabled reflection on some aspect of ‘heritage’ as traditionally defined. The engaged arts as a living, socio-political energy is simply not something they can acknowledge. This may be to put the case too strongly but it relates directly to a conversation I had with Teresa Pinto Coreia, from ICAAM – Instituto de Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais Mediterrânicas, Universidade de Évora, after she had given a very interesting presentation called: Landscape values under pressure: tensions in the management of extensive silvo-pastoral systems in Southern Iberia.

I recognised many of the difficult issues she spoke of from my own interest in conflicted rural areas. Whether in terms of the difficulties facing farmers in upland regions in the UK, in rural Ireland in relation to small-scale family turf-cutting, or from what I know of the history of local resistance to the formation the Wadden Sea National Parks in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands and that, in Germany and Denmark, constitute the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Wadden Sea. Put simply, it is the problem of a clash between small-scale largely rural communities in which authority still largely based on specific forms of performativity in a given taskscape, and the worlds of academic research and governance which take as given an understanding of authority predicated on their own methodological and discursive sophistication as underwritten by a logocratic realpolitik. Two radically different ways of understanding and so acting in the world. Her response to my making something of the points outlined above was polite incomprehension and the view that, by working with students in the university, they would find a way forward.

The whole point of people like myself, Simon Read, Ciara Healy and others with an imaginal arts aspect to their compound practice attending the conference might be said, as I tried to explain to Teresa Pinto Coreia, to show that certain types of art practice are ideally placed to mediate between these two radically different ways of understanding and acting in the world. However, if that brief conversation was anything to go by, I certainly failed to do so. Not I believe for any lack of trying on either of our parts but because, as a professional group, those in the arts remain mentally marginalised by academic thinking, located as we are off to one side of the logocratic hierarchy that underwrites its realpolitik. (As a fairly distinct group we presented no keynote to the assembled attendees that could have facilitated such an exchange at the level of intellectual debate). Because of this institutional marginalisation the arts as an informed way of knowing the world – other perhaps than landscape architecture seen as an art – has no real role in UNISCAPE as an alliance of European institutions other than as ‘passive heritage’. This in turn reflects, of course, the marginal place of arts and music education as an alternative mode of understanding in the education system as a whole. The consequences of this fundamental lack in a culture of possessive individualism are now horribly clear in the political and socio-environmental situation of the UK.

It’s not for me to suggest how, as an international organisation, UNISCAPE might address this situation. However, if an initiative to address this were to be launched, it might perhaps be done from Ireland. There ‘cultural heritage’ in the sense of place or landscape may be somewhat less isolated from living forms of imaginative culture and thinking than in many other countries. So, while in some senses I was deeply disappointed by the situation I’ve tried to indicate (perhaps too clumsily) above, I still see Ireland as a site of promise and a source of guarded optimism, particularly now that the UK has turned it’s back on the EU project rather than trying to reform it. I also see UNISCAPE as an important international organisation with an annual conference I was more than glad to attend, if only because it enabled me to see the issues outlined above more clearly.