In January this year I had an invitation from Michaele Cutaya, Katherine Waugh and Connor McGrady to participate in a two-day symposium PROPOSITION: AN ART OF ETHICS. This was to take place at the Burren College of Arts, supported by Clare County Council and the College, from Friday 11- Saturday 12 March 2016. They proposed to bring together around 10 artists, theorists and curators from Ireland and abroad to engage with the notion of Ethics and Art and to keep the form of the symposium as well as individual contribution quite open and responsive.

Michaele wrote to me that what had “prompted this event was on the one hand the feeling that ‘business as usual’ in art and art events organization is rightly challenged, and on the other a growing wariness with the way ethics is imported into the arts with its apparatus of prescriptive norms and judgments. In this context we thought that the immanent ethics of Spinoza might be an interesting proposition to explore: that is an ethics arising through practice and not preceding it. Or as Deleuze put it more eloquently: “Spinoza’s ethics has nothing to do with a morality; he conceives it as an ethology, that is, as a composition of fast and slow speeds, of capacities for affecting and being affected on this plane of immanence. That is why Spinoza calls out to us in the way he does: you do not know beforehand what good or bad you are capable of; you do not know before-hand what a body or a mind can do, in a given encounter, a given arrangement, a given combination.” (Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy p. 125)

“This not a philosophy symposium but one aimed at art practices, and an invitation to think through some of the difficulties encountered when one is dealing with both ethical and aesthetic considerations”.

Despite the fact that I have only a fairly hazy notion of Spinoza’s ethics (and indeed of most philosophical debate more generally,(not to mention a perverse tendency to regard Deleuze as that bloke who was Felix Guattari’s sidekick for a while), I happily accepted.

When I arrived in the Burren on Thursday evening this week I discovered that the three organisers had assembled a fascinating collection of participants. These included Maria Kerin (with whom I had corresponded in the past but not met), Suzanne Walsh, Aislinn O’Donnell, Vivienne Dick, Glenn Loughran, Seamus McGuinness, Ciaran Smyth (whose partner Ailbhe Murphy I have met previously in both Dublin and Galway) , Susan Stenger, Connor McGrady, Glen Loughran, and David Burrows. This lively mixing of people and concerns ensured that we had viewpoints evoked from a spectrum of interests across philosophy and theory, music, performance, film, curation, socially-engaged visual art, education, poetry and other forms of writing. The attendants at the event appear to have been either staff and students from the college or a range of interested individuals from the west of Ireland more generally who had travelled the distance to join us.

Having freed us from the constraints of the academic conference and invited us to adopt whatever form of presentation or provocation seems to us appropriate, the organizers generously fed and housed us. They then set us in motion to find our way through our allotted task with the minimum of overt guidance.

A long and sympathetic conversation with the musician, singer, performer and artist Suzanne Walsh, along with a number of others on the Thursday evening, started to open up some interesting shared concerns and possibilities. After I had introduced Suzanne to the lyrics and music of the Borders ballad Tam Lin – neither of us could quite reconstruct the trajectory of the conversation in retrospect – she generously offered to sing some verses as an introduction to my presentation on listening on the Saturday. This despite the fact that it would mean her having to get to grips with an entirely new tune and set of lyrics in a period of little more than what already looked like being a very busy twenty-four hours.

On the Saturday morning, when Suzanne had ‘opened’ for me in this way by singing her chosen verses beautifully, accompanied by a drone from her accordion, I read the following text:

Listening

There’s a form of listening that enables us to translate across categories, disciplines, hierarchies, boundaries and modes of being. It also allows me to use the art of conversation to navigate the volatile space between various practices – art, activism, teaching, maintaining communities of interest, researching, writing, and so on.

A long monologue about listening and conversation would be self-defeating. Instead I’ll try to evoke, using four related sequences, some difficult conversations with texts and people I respect, hoping that these will seed new conversations.

One

Paul O’Neill suggests there’s a fundamental relationship between art and a certain type of conversation. A conversation that waits for what’s unforeseen, enabling ideas to converse with time itself unrestricted by any fixed or predetermined end. A second curator – Monica Szewczyk – pinpoints the value of this:

“If, as an art, conversation is the creation of worlds, we could say that to choose to have a conversation with someone is to admit them into the field where worlds are constructed. And this ultimately runs the risk of redefining not only the ‘other’ but us as well”.

That risk – or hope – of mutual redefinition might be linked to socially engaged art but it also raises questions about the identity ‘artist’.

The practice of conversation as an art relates closely to Gemma Corradi Fiumara’s work on listening as an attempt to recover: “the neglected and perhaps deeper roots of what we call thinking”. Necessary work because we have internalised a mentality that: ‘knows how to speak but not to listen’ that, in turn, feeds a culture of ‘competing monologues’, of possessive individualism.

This conditions our relationship to others, but also to ourselves. If we don’t listen to our own ‘several-ness’, our different personas, how can we recognise them as the internalization of community constituted by our multiple attachments, connections and relationships? So listening in Fiumara’s sense is both political and ethical. It challenges possessive individualism’s silencing of our communal constitution, our multiplicity, our porosity, our sharing the contingencies and connectivities that animate the ‘us’ that we are.

Two

A David Napier writes that what is extraordinary is not how radical artists can be, but that their sense of their persona as ‘artist’ can be so conservative – a persona that, because of its assumptions about unique personal creativity, tends to exclude all other activities that define a person’s connectedness and ontological status. This presumption of monolithic singularity and uniqueness is used to model creativity by possessive individualism. This not only permeates our culture, politics, and social organisations, it informs the more fundamental complex of assumptions we make about personhood, nature and society.

Having examined the relationship between art and science, the Czech poet and immunologist Miroslav Holub argues that to focus on their differences is to distort social reality. Both modes of creativity receive only a tiny percentage of their practitioner’s time. The bulk of that time is actually spent on numerous other tasks, many of them mundane and unrelated to their specialisms yet, despite that, rarely wholly uncreative. Any conversation is necessarily enmeshed in, and partly determined by, all the synergies and tensions of our multiple tasks. This state of affairs is perfectly captured in Geraldine Finn’s observation that: “we are always both more and less than the categories that name and divide us”.

Pauline O’Connell once characterised her practice to me, in a memorably ironic tone of voice, as that of a ‘compound cur’. (We had been talking earlier about attitudes to working dogs in rural Ireland). That conversation gave me an image of the spectrum of artist’s ambition – from those who compete to be “best of breed” to those who –perhaps sometimes reluctantly – can celebrate the values of the “compound cur”. I share this image with you because it relates to Yuriko Saito’s challenge to ‘the aesthetics of exclusion’, to her argument that ‘everyday aesthetics’ informs and supports the emergent ethics of civic environmentalism.

Three

For years I’ve work with doctoral students, usually artists interested in questions about links between memory, place and identity. I have two main tasks. To help them navigate the Byzantine world of academic research protocols, and to act as a critical and solicitous fellow traveller. Both tasks involve numerous conversations to translate between our different values, skills, concerns and framings. There seem to be similarities here with the work of socially engaged artists like Jay Koh and Petra Johnson, who use conversation, focused by listening, to act on particular intersections of social, political, and ethical space.

That said, I’m often uncomfortable with the discourse of socially engaged art. For example, Grant Kester begins Conversation Pieces by setting aside object makers as content providers, to focus instead on the performative, process-based approach of context providers. I find this unnecessarily reductive. The work I do sometimes generates objects that focus or conclude some aspect of an on-going, performative, process. Those objects may be exhibited, published or performed. But it remains the case that their production also renews or extends contexts for on-going conversational work.

I wonder if these discriminations within art discourse aren’t sometimes a way of avoiding more controversial issues like the hierarchical distinctions between art and other modes of creativity? Claire Bishop, for example, reluctantly accepts teaching as an artistic medium, although she worries about the resulting epistemological problems. But, faced with the possibility of art as a medium for teaching, she falls silent. That silence returns me to a very brief conversation I had with Joseph Beuys in 1972. It ended with him saying: “always remember, education is more important than art”.

Four

As I understand them ‘art’, ‘education’, ‘ethics’, and ‘conversation’ share a common precondition – listening as active noticing. For Mary Watkins this is: “a careful, noticing attention that is sustained, patient, subtly attuned to images and metaphor”, and “able to track both hidden meanings and surface presentations”. It has a subversive dimension because it resists the mania for hyperactivity, including the frantic pursuit of cultural novelty, that possessive individualism needs to perpetuate itself. Instead it allows us to participate, slowly and observantly, in the specific particularities of our life-worlds as these happen to manifest themselves. It’s inclusive, open to the materiality of the world and to modes of non-human being. So the poet Kathleen Jamie, asked by a neighbour if she had prayed for her partner while he was dangerously ill in hospital, replied that she hadn’t. She writes, however, that she:

“… had noticed, more than noticed, the cobwebs, and the shoaling light, and the way the doctor listened, and the flecked tweed of her skirt, and the speckled bird and the sickle-cell man’s slim feet. Isn’t that a kind of prayer? The care and maintenance of the web of our noticing, the paying heed?”

I’ve very grateful to Michaele, Katherine and Connor for organising this fascinating event. It not only allowed me to test out some thoughts in public, and to meet up with old friends like Pauline O’Connell, but also to make a whole host of new friends with whom I look forward to working in one way or another with in future.

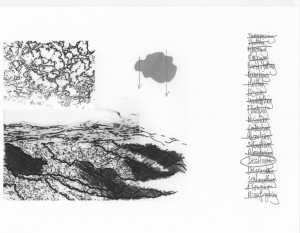

Which leaves only the vexed question of the relationship between art and ethics. I’m not sure I have anything much to add here to what I said on Saturday morning, despite a fascinating three days of exchange, powerful impressions and debate. I was moved by the slow intensity of the movement piece performed by Maria Kerin and her movement partner, as I was by Seamus McGuinness’ work with the families of young suicides. I found plenty to interest and provoke me. including papers by both Glenn Loughran and Aislinn O’Donnell – each challenging and encouraging in their rather different ways. I was both intrigued and moved by the film by Vivienne Dick and by the musician Susan Stenger’s extraordinary musical journey, which has recently led her to make Sound Strata of Coastal Northumberland which I can only call a sonic deep mapping of the Northumbrian coast. That said, I’m uncertain as to what it all adds up too.

This is absolutely not in any sense to suggest that we “didn’t get anywhere”. Only, perhaps, that the “where” in this case is best understood as a highly specific form of localised and particularly constellated relationally; one that, in addition to a willingness to listen, was (and maybe still is) contingent on degrees of openness, goodwill, modest aspirations in terms of what can reasonably be expected to be done, and the necessary attributes of human kindness and consideration that make living possible in a world without any hope of redemption but not, for that reason, without enchantment or certain forms of joy. Samuel Becket’s words will serve as a suitable coda here.

Fail, fail again, fail better.