Last night I worked for the first time in about three months. With my friend Luci Gorell Barnes I run a workshop that responded to the artists John Wood and Paul Harrison’s Erdkunde – itself a new video work responding to Bristol City Museum’s collections. (These were not, it has to be said, much in direct evidence in the film, but so be it). After meeting at the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery to watch the Erdkunde film we walked up to the RWA (where Luci and I had already spent a frustrating half hour struggling to get PowerPoint up and working) and assembled in the small upstairs studio. I started us off by linking some of the key features of a deep map to what we’d just seen. What I said is pretty much as follows.

The word “Erdkunde” can be literally translated as ‘physical geography’ – but in German ‘Erde’ can mean ‘world’, ‘ground’ or ‘earth’, so it’s a very inclusive term. That makes it a perfect title for John Wood and Paul Harrison’s work. Their interest in collecting, cataloguing, and displaying various kinds of information – through notes, sketches, photographs, thoughts, ideas – questions how we look at things, identify them, talk about them. To do all that we use given systems of classification, even though our actual experience is always somehow both more and less than the systems and categories we use to tidy up the world. Deep mapping asks questions about the official categories we apply to space when we start to think about our experience of place.

So ‘deep mapping’, like the Erdkunde exhibition, is a way of questioning the relationship between official classifications of what is or is not important and our own immediate experience. Of course all places are shared to some extent, so our sense of place is always a combination of lived experience, given information, and various kinds of memory. Any deep mapping exercise begins by asking: “what needs to go onto a map of this particular place” and, because a place is always changing, being re-shaped, deep mapping is in turn always as much about time as it is about space.

I can identify each of these four snapshots taken in Bristol in terms of a particular place, but they are also evocations of different times – the slow change and decay of architecture periods over against the span of a human life or the growth of a sunflower.

We make sense of places through sharing stories, which are like crossroads where what’s important to us personally meets shared histories and social values. Here’s a story about a place in Bristol that’s no longer there. This was a medieval church dedicated to Saint Leonard – patron saint of prisoners – down on the Westgate, one of the original entrances to the medieval city, which became known as St Leonard’s Gate. This medieval church was in the way of ‘improvements’ to this area of the city that, in the C18th, needed to rework itself as a port in order to accommodate its expanding trade. So the civic authorities destroyed an ancient religious building dedicated to a saint who, according to legend, had the right to liberate prisoners and, having done so, to gave them land to live off. Ironically, they did this in order to facilitate the slave trade. I’m telling you this because one of the things deep mapping does is try to make visible the tensions between what’s remembered and what’s forgotten in constructing a sense of place. In doing so it inevitably asks questions about our values.

So deep mapping is a way of visualising the mesh of social tensions – both productive and unproductive – inherent in the processes of remembering and forgetting. Since these processes happen at the point where the personal and the public meet, deep mapping is always in some way collaborative. This slide shows a project by Rebecca Krinke called Seen / Unseen – the mapping of joy and pain where she and her students took a plywood relief map of Minneapolis / St Paul into the park and asked people to map where they had experienced joy and pain in their city. It’s purpose, however, was really as much to make an intimate public space for people to share their experiences and the stories that make Minneapolis / St Paul not just a city on a map but a lifeworld held in common as it was to make a specific art work.

Luci then talked about her Atlas of Human Kindness and opened up the parameter of the evening’s thinking by referring to ‘narrative mapping’ rather than ‘deep mapping’.

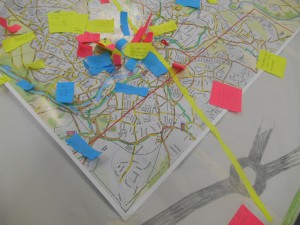

We then asked the participants to plot particular locations that mattered to them onto a big map of Bristol, using PostIts colour-coded according to three general types of experience, so as to create a high-speed pro-deep map of Bristol. Here are three photographs Luci took:

It seems to have been a good evening for the participants and it was certainly good for me to be ‘back in the saddle’ in terms of doing something educational, having been wholly emersed in family matters and the new house for so long.

So what has any of this to do with ‘autumn in suburbia’? Perhaps nothing, literally speaking, but I find it increasingly hard to take things entirely literally these days or, indeed, to keep the separate elements and levels of my life from seeping into each other across the usual boundaries we erect. At sixty-five and recovering from six weeks illness in a house that’s been half building site, I am tending to feel a bit autumnal myself, so very much in tune with the current season of ‘mellow fruitfulness’ and decay. And to find myself living in suburbia is, for me, to be living in a space that is neither truly urban – I got something of a buzz from being out on Queen’s Road at seven at night yesterday, the familiar feeling of the street on Friday night just starting to get busy – nor (despite the plentiful evidence of foxes, owls, etc.) rural in any meaningful way.

The world in which I now live is characterised by reticence – there’s little sense of neighbourly communication – on one hand and excess on the other. (Oddly, John Wood and Paul Harrison’s reticence in their film seemed to me to resonate oddly with the suburban world, their piece a kind of absurdist ‘Janet and John’ exercise directly at the culturally sophisticated). Excess out here, on the other hand, has seemed to me to be personified by the plethora of vast 4x4s – often two to a house – that I see driven by small, determined women in a hurry with little sense of how to manage the mechanical beast they’re in charge of. (Yesterday I watched as one such women took three goes at backing into her own drive, reversing clearly being something of a problem). Their husbands, large, corporate types, tend to have a better grasp of the beast, but seem to regard speed limits as some kind of personal affront.

I could go on but there’s no point in airing my prejudices – unnecessary consumption and similar forms of selfishness and excess are hardly the prerogative of the Bristol suburbanite!