[This the third of forty-nine narrative sections that make up Convergences: Debatable Lands Volume 3, the concluding work of my Debatable Lands deep mapping project. The complete work is now available on request as a pdf. If you would like a copy, please contact me at: iain19biggs@gmail.com].

Editor’s note. In 2004 I initiated a project that became ‘8 Lost Songs’, an artist’s book that included a CD of music, prints and a map on silk. It was made with two friends, the musician Garry Peters and the book designer Jonathan Ward. The book was produced in a limited edition, but has a second, digital, life. It was the second publication in an ongoing ‘deep mapping’ project, begun in 1999, and was my first attempt at ‘a true story that never happened’. In a note among her papers Flora suggests that, because of what happened to her friend Cat, I return to ‘8 Lost Songs’. What follows is a slightly revised and further annotated version of the original text, but should now be read in the light of Flora’s email to me about Cat’s later life and early death, reproduced above.

‘8 Lost Songs’ – Preface

The circumstances that led to this project require some comment. In 1999 I began work on a book with a scholar and artist who, for reasons of his own, wished to remain anonymous. He was referred to only as A. The book we produced – Between Carterhaugh and Tamshiel Rig: a borderline episode – was published by Wild Conversations Press, and appeared in January 2004. A. had retired from all forms of public life that year, something he had been contemplating for some time. In the autumn of 2003, in preparation for his retirement, he kindly sent me material relating to various ongoing and unfinished projects he thought might interest me. The material that resulted in Eight Lost Songs immediately caught my attention.

The content of this publication has been taken from various sources. A. undertook almost all the original research on which the publication is based, which I then wrote up in the form it appears here. The ‘ethnographic notes’ on the eight lost songs themselves are, apart from a few corrections, reproduced here as cat (as ‘Alison Oliver’) wrote them. My own role has been to edit and assemble the material for publication, to produce the images, to provide some additional contextual material in the form of footnotes, and to invite Gary Peters to respond musically to what we know of the ‘lost’ material.

Introduction: ‘8 Lost Songs’

This project is best described as a celebration but, paradoxically, one that has at its heart several absences. It responds, in words, images and music, to such information as we have about a set of eight lost songs linked, as far as we know, by their connection to the former parish of Southdean. We know nothing about these songs beyond what is set out in Alison Oliver’s notes, reproduced below.

No attempt has been made to ‘reconstruct’ the songs, as individuals like Sir Walter Scott might have done in the past, not least because there is simply not the information available to do so. Instead, we have responded, using what information we have and our imagination, to the enigmatic trace of the various individuals whose lives provided the focus around which the original songs appear to have taken shape.

The background to ‘8 Lost Songs’

On May 6th, 1969, ‘Alison Oliver’ (Catherine Douglas), who claimed to be a Canadian singer of Scottish decent, played a tape to the independent record producer George Canning. On the tape, she had recorded herself playing and singing what she claimed were eight traditional songs. She also played and sang at least two of these songs ‘live’ to Canning. Oliver, an unknown singer working the northern folk club circuit, had spent almost eight months getting an appointment with Canning. When they finally meet, he was clearly impressed both by her singing and playing and by the material itself. He asked to borrow the tape so that he could play it to associates but, unfortunately for us, she refused, saying she’d rather return and play the material ‘live’. After some discussion, he agreed in principle both to help her cut a proper demo and look for a recording contract for her, providing his associates were as impressed with the material as he was. The only note of discord in an otherwise positive meeting came when he asked Oliver why, if these were indeed traditional songs, he had never heard any of them before? Oliver was clearly uncomfortable with this question and launched into a long, convoluted story about how her family had taken an old ballad manuscript to Canada with them when they left Scotland, where the songs had subsequently been forgotten.

As Canning later told Sarah Norton, his personal assistant, he didn’t believe this story and had implied as much to Oliver. At this point she had become defensive and insisted that, while the arrangements were hers, both the tunes and lyrics were traditional. Canning dropped the issue but, although the two parted on good terms, he told Norton to write to Oliver and tell her that, given her insistence that these traditional songs came from a manuscript in her family’s possession, she must bring the original manuscript with her when she next came down to London.

Some days later a fire broke out in the small, isolated cottage Oliver rented. No trace of a body was found in the burnt-out room and to all intents and purposes she disappeared.

That might have been the end of the matter had A. not found a thick envelope of material tucked into the back of a very battered copy of the first volume of Child’s English and Scottish Ballads, which he noticed at a car boot sale. The book had ‘Alison Oliver, 1965’ written inside the front cover and, to judge by the many marginal notes, she had made a close reading of its contents. A. bought the book and became intrigued by the narrative implicit in the collection of documents. He decided to find out what he could about the circumstances surrounding the loss of the eight songs. The documents included a letter confirming Oliver’s appointment with Canning and another from Norton passing on Canning’s request that she bring the manuscript to London. They also included what he took to be the draft ‘sleeve notes’ reproduced below.

Like Canning, A.’s initial assumption was that Oliver had simply ‘faked’ a set of tradition ballads, using Child as a basis, and that the notes were intended to lend an air of authenticity to her forgery. However, after some extensive research A. realized that, although almost certainly faked, the ballads were in many respects highly sophisticated. All the figures referred to in the notes had not only existed, they each had some link to Southdean. In addition, the sleeve notes’ references to other ballads, some of which are not in Child, together with Oliver’s account of local features such as the state of the site at Hilly Linn, appeared to be entirely accurate. This suggested that, at the very least, the lost songs were a deeply researched forgery. His investigations confirmed that the songs were not known locally and all the experts he consulted said it was very unlikely that they were indeed ‘traditional’ songs.

Regardless of the question of the exact provenance of the songs, it seemed to be a little short of tragic that the ‘Sowdun parish blues’, as Norton recalled Oliver laughingly calling them during her meeting with Canning, have not survived. Canning had an ear for strong material. He would hardly have offered to help an unknown singer unless Oliver’s performance, and the quality of the material, were outstanding. The notes suggest that, whatever their origins, these songs represented a rich and varied set of insights and/or imaginings about lives in Southdean parish between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Eight ‘Sowdun’ (Southdean) songs: Alison Oliver’s notes

One: ‘The Crow Child’ or ‘Ranting Jamie and the Witch’s daughter’. Of the eight Sowdun Parish songs, ‘The Crow Child’ is the longest and strangely, the closest in style to the old Borders ballads such as ‘Thomas Rhymer’ and ‘Tam Lin’, with their seamless blending of the mundane and supernatural. However, unlike the almost archetypal characters in the old ballads, the figure of ‘Ranting Jamie’ Courton appears to be based on an historical person. We know from historical records that, in 1670, the radical Covenanter James Courton of Southdean was drowned when the government-owned ‘Pride of London’ sank of Deerness. Courton had been a prisoner on the ship awaiting transportation to the American colonies. Other elements in this song remain, at least in terms of any historical basis, either confused or obscure.

It has been suggested by some ethnologists, however, that the first third of The Crow Child refers to the death, in 1615, of a young Shetland woman condemned as a witch for fostering a fairy child which she hid in Caldback hill. Some have assumed that she had an illegitimate child by a sailor and tried to hide this from the Kirk. Caught nursing her child, she claimed only to have taken pity on a chance-found ‘fairy’ child. However, any association with fairies, however charitable, was liable to be treated as a capital crime and she was subsequently executed. The child is believed to have survived, to have later escaped to Orkney, and subsequently to have become one of the most feared and respected ‘howdies’ (wise women with supernatural powers) in those islands’ history. She, too, is said to have had a daughter at a time when most women were past such things. The reference to the ‘crow child’ comes from an Orkney story that goes as follows.

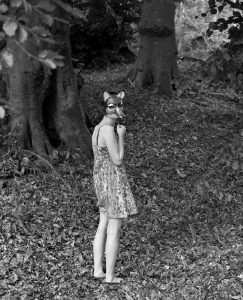

‘The Crowlady’ Ruth Jones (photograph Phil Collins).

A young girl went out to play on the hill above her mother’s house one day with her friends. After a while they became bored with all their usual games and wondered what to do. The girl child, daughter to the ‘howdie’ Mattie Finn, said: ‘I’ll show you something my Mam taught me’. She stood on a great stone, flapped her thin arms, inviting her friends to catch her, turned into a great black crow that flew low over their heads. Astonished but delighted, they ran laughing and calling after the crow until they were tired out. The crow returned to the great stone and began to change back into a little girl. But the children soon realised something was wrong. What hopped and shook on the stone was a young girl with the head of a great black crow. They became frightened and, after whispering together, sent the youngest of the group to find Mattie Finn. Mattie was standing at doorway talking to a sea captain.[1] She gave the poor child a black look when she interrupted them but, when she heard what had happened, ran straight out to the hill. Coming up to her daughter, hopping and crying on the great stone, she called out some words and at once the crow child had her own head again. Mattie took her by the shoulder and gave her daughter a good hard slap, saying: ‘that’s to teach you not to forget what you’ve been taught’.

How the story of Mattie’s daughter and her grandmother’s terrible death became linked to the loss of the ‘Pride of London’ and the death of a Southdean Covenanter is not known. It must be assumed that a singer took a muddle of local island tales of ‘howdies’, fairy lovers and cursed sailors and, sensing in them the abiding thread of conflict between the ‘man of God’ and the woman who follows other paths, gave them a new form and currency through the link to an historical event, the deportation and death of ‘Ranting Jamie’ Courton, a typical example of the ‘migration’ of traditional material.[2]

Two: ‘The Righteous Fugitive’. This song was very probably inspired by the life and deeds of the Rev. William Veitch, an outlawed Covenanter and outdoor preacher, who became well known in the parish of Southdean and surrounding area for his ability to escape capture by ‘the persecuting soldiery of the bigoted Stewarts’. A local account alleges that ‘the staunch Covenanter own his immunity from capture to an underground hiding place on a heather clad knoll, so deftly fashioned and advantageously situated that he could view the landscape and watch the military as they fruitlessly searched the moorlands endeavoring to ‘track the fugitive to his lair’. The description of Veitch’s ‘lair’ in the ballad suggests this may have been the barrow formally known as ‘Carter’s Howe’ that overlooks the Carter Burn and the old road to Otterburn as it runs east across the parish. If this is the case, there is a certain irony in the fact that this most zealous of Covenanters owed his life to the one feature in the local landscape still associated with the pagan (‘fairy’) world remembered in the ‘supernatural’ Borders ballads.

Three: ‘By Katey’s Cross’. The character of ‘Auld Peter’ at the center of this song is said to be Peter Oliver, a Southdean fiddler and supposedly the last person in the parish to see the ‘good neighbours’, as the fairies were euphemistically known. This same sighting was reported by his son, Robbie Oliver, to a local historian at some point early in the nineteenth century. It was described as having taken place somewhere on White Hill, to the north of the old Leatham chapel. The central event of the song resembles later, better known stories, for example that told by Son House of Robert Johnson, in which musicians are said to have sold their souls to the devil to play better. The Queen of Elphane is an appropriate substitute for the devil here, since the Church traditionally linked them, claiming that she paid him a human tithe every seven years. (The original basis for this tradition can perhaps be traced back to elements of pagan ritual associated with the sacrifice of the king to the triple Goddess, who became in turn the Queen of Elphane and featured prominently in Scottish witch trials).

The exact location of the cross roads where Auld Peter meets the queen, once the site of a local market, is now lost. Circumstantial evidence suggests, however, that it may have been located at the point where the old drove road running up from Leatham crosses the main Otterburn road before fording the Carter Burn.

Four: ‘Wandering Jamie’. ‘Wandering Jamie’ would appear to record the adventures of a certain James Hume Turnbull ‘of Hyndlee’, who was born 1842 and, like many of his generation, left the parish twenty-six years later to seek his fortune in the New World. It has been suggested that, having fallen foul of the law in Scotland, the historical James did indeed cross to the New World. (An undated warrant for the arrest of a James Hume Turnbull, a suspected ‘Resurrection Man’ working in Edinburgh, can be found in the Edinburgh Records Office. Apart from the name, however, there is no evidence to link these two men and it is likely that the warrant predates the birth of Turnbull of Hyndlee. From the notes, it appears that this song may have been not dissimilar to the traditional ballad known as ‘Lord Franklin’). He is said to have travelled deep into the northwest of Canada where he died of his wounds out on the frozen sea following a mortal battle with a great white bear. Beyond the reference to ‘Hilly Linn above the Jed’ that sits oddly in the second verse and may be a later addition, there is nothing to link the song directly to Southdean. It none-the-less accurately reflects a major facet of the parish’s history – the exodus from the hill ‘farmtouns’ to find employment either in the big cities or in the New World. The former farmstead of Hilly Linn is now no more than a name on the map and a few moss-covered stones beside a young rowan tree in an area of rough ground between rows of recently planted forestry.

Five: ‘Bold Helen’. Some circumstantial details in ‘Bold Helen’ suggest that it may be based, if only in part, on events in the life of Helen Gerdin of Dykraw ‘in Jedburg Forest’ who, on the third of June 1675, was fined for forestalling the market at Jedburgh by selling meat before ‘the ringing of markitt bell’. While the song may also refer to other actual events in Helen’s life, it probably draws for the most part on much earlier material, now lost, celebrating the wit and cunning of independently minded countrywomen in their dealings with husbands, neighbours, lovers and the authorities. The vivid account of Helen’s erotic adventure in verses eleven to thirteen, highly unusual in a ballad of this kind, is not unlike the erotic encounter of the Waggoner and Jenny in the English ballad ‘Ge Ho, Dobin’. Both songs make evocative use of parallels between the sexual act and the characteristic motions of a form of transport – the bumping wagon in ‘Ge Ho, Dobin’ and the actions of the vigorous oarsman in ‘Bold Helen’.

The ‘mill race’ where Helen half drowns her husband lies to the southeast of the site of the old Sowdun church and its course is still just visible in the field behind Sowdun farm. ‘Tam’s Rig’, where Helen hides from the Sheriff’s men, is almost certainly Tamshiel Rig, where the remains of the shielding can still be seen near the site of an Early Iron Age settlement and fort now destroyed by modern forestry planting.

Six: ‘The Death of the Rev. Thomas Thomson’. The account in the parish record states that the death, in 1716, of the Rev. Thomas Thomson after a two-day illness was the result of ‘supernatural intervention’. (The exact nature of which is not recorded, although the song itself suggests that it was the result of a ‘fairy’ curse). Like other ‘Sowdun’ songs collected here, this one hints at an underlying and deeply felt conflict between the ‘rational’ Christianity of men like Thomas Thomson and an earlier, ultimately pagan, world view that retained much of its power in the remote upland farms into the early nineteenth century. Given her sudden appearance and disappearance in the snow-covered landscape ‘beside the Carter Burn’ on a day when a wind is blowing from the north, we can reasonably assume that the ‘fair hunting lady’ who ‘looked at Thomas with a cold eye’ after he had scorned the ‘poor tinker’ is no ordinary woman. She resembles the ‘Queen of Elphane’ in the ‘supernatural ballads’ and as she is discussed by Robert Graves in The White Goddess.

Thomas Thomson’s son James (1700-1748) was born in Southdean and became one of Britain’s most influential poets of the period, inspiring Turner, Wordsworth and Coleridge. Perhaps the ‘fair lady’ felt she owed him some recompense for what she had done to his father.

Seven: ‘Black-eyed Border Maid’. Oddly, the ‘black-eyed heroine of this relatively recent song remains anonymous, despite herself making it clear that she is a descendent of ‘Black Jannet’. This is the ‘Black’ Jannet Grieve‘ of Suddonrig’ who married in 1762, one of the many formidable women in a family well represented in the parish. She in turn is probably the granddaughter of the ‘bonny Jannet Grieve’ who hid ‘Bold Helen’ in the song of the same name. While it will appear singularly odd to a modern listener that reference to a ‘green mantle’ should give rise to such consternation in the Grieve family, the reasons for this become obvious when we know that ‘greens’ is an ‘archaic’ expression for sexual intercourse, and that a ‘green mantle’ refers to ‘a roll in the grass sometimes, but not always, associated with loss of virginity’.[3]

Eight: ‘Margaret and Isobell’. It is a matter of historical record that Margaret Chisholm, the wife of a traveler named Thomas Olipher (or Oliver) was fined in 1640 for wounding a certain Isobel Leidance in the face. Like the Rev. William Veitch, Thomas and Margaret appear to have used a local barrow for either shelter or, perhaps more likely, storage of dubious goods, which would explain Isobel’s ambiguous taunt about abusing the hospitality of the ‘Elphane Queen’. (Tempting as it might be to suggest that this barrow is the same ‘Veitch’s lair’, otherwise known as Carter’s Howe, linked with ‘The Righteous Fugitive’, there is no evidence for this). However, it can be noted that there are a series of long, twisting ‘banks o’ gravel grey’ clearly marked on the first ever Ordinance Survey map as lying along the edge of the ‘haughs’ that border the Black Burn, just as they do in the song. Whether these were the location of the epic fight between the two women, or indeed whether that fight inspired the song’s account of the protracted and increasingly surreal battle recorded in the song, hardly matters. Whatever the case, it is a perfectly example of the peculiar, black humour found in certain ballads.

Alison Oliver.

[1] On the islands the ‘howdies’ or ‘Finns’, said to gain their power from the fairy folk, were believed to be able to summon up fair or foul winds and could be persuaded to sell a fair wind for good silver.

[2] Alison Oliver’s notes resonate with Rebecca Solnit’s observations about country music. Solnit observes that: ‘the old Scots and Irish ballads were as gory and gloomy, but they are generally heirlooms now, and country and western music is their immigrant bastard grandchild, something that came into its own only half a century ago and hasn’t died out yet […] For me country’s definitive song might be ‘Long Black Veil’, whose way with time is straight out of the Bronties. A dead man sings ten years after his hanging for a crime he didn’t commit, but his only alibi is unutterable: ‘I’d been in the arms of my best friend’s wife”, who when he died “stood in the crowd and said not a word”. Now she wanders the hills in a long black veil and, well, visits his grave where the night winds wail. Hills and night winds are still there, are reliable, are what you have in the end’. See Rebecca Solnit ‘Diary – An account of driving in the Serra Nevada / New Mexico driving east’ in the London Review of Books, 9th October 2003. I would argue, however, that the approach to time she refers to is less that of the Bronties than of traditional Scots and Borders ballads that deal with the dead and with revenant beings, for example ‘The Unquiet Grave’, ‘Clerk Sanders’ and ‘Sweet William’s Ghost’.

[1] This expression crossed the Atlantic with the old ballads. In 1972, Ron ‘Pig Pen’ McKernan would introduce the aside: ‘I don’t want to miss my greens’ into his rendering of Clark and Resnick’s ‘Good Loving’. The concluding lines of ‘A Ballad of Andrew and Maudlin’ makes explicit the reason for the family’s consternation:

They laid the Girls down, and gave each a green mantle

While their Breasts and their Bellies when Pintle a Pantle.