[This the first of forty-nine narrative sections that make up Convergences: Debatable Lands Volume 3, the concluding work of my Debatable Lands deep mapping project. The complete work is now available on request as a pdf. If you would like a copy, please contact me at: iain19biggs@gmail.com].

After the service

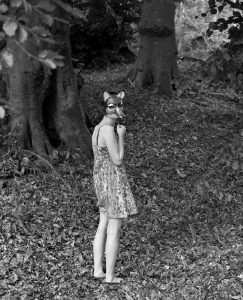

I was probably the only person of Flora’s generation at her funeral who had not known her since childhood, had never called her ‘Faun’, short for ‘Fauna’. (As a precocious ten-year-old, James Aitcheson had insisted that, as a vet’s daughter, ‘Flora’ should have been christened ‘Fauna’. Shortened to ‘Faun’, this became a lifelong nickname). So, over the best part of a life-time she had been ‘Flora’ and ‘Faun’ both. I had come to known her much later, as a correspondent who became a good friend.

Chew Green

After the funeral, I turned abruptly left outside the old kirkyard, unable to face the obvious curiosity of the people gathered in the car park, and let a steep track take me up to a plantation above the village. Although the breeze was too light to disturb the trees, the late sunshine now occasionally broke through the cloud to warm the new-turned earth over her body. Chance turned me up a narrow ride into the scented darkness where, ahead, the thin grass, struggling up between the tire ruts, strained towards the light. Grass a shade of green that recalled Flora, not sick in hospital as I had last seen her, but at our only previous meeting. Sitting across from me in the Baltic’s café on a cold spring morning, she had cradled a large mug of just such a green as if warming her strong narrow hands.

The plantation drowsed fitfully in the late afternoon light and a childish fear spurred me on. Here, as in a dream, you might meet a black wolf the height of a man, or else one of the ‘good neighbours’. The churned ride took me steeply up hill, then out into a clearing. As I emerged the wind finally returned, so that the high trees murmured like the sea. I passed a half tumbled stell, its floor now a patch-work of yellow grey, deep pink, and strangely mottled emerald sphagnums, protected by the stell’s crumbling walls from the encroaching trees. Walking over a second rise I found myself in a sudden wasteland created by acres of clear felling. Rutted soil, trapped water glinting like splintered glass, Sitka stumps at crazy angles, brambles and rosebay willow-herb forcing themselves through the irregular heaps of rough trimmings. I knew that in time grass, balsam, and mosses would slowly heal the scars and hollows, cover the bare bones of the land but, hollowed out by grief, I could take no comfort in that knowing.

The light had almost gone by the time I returned to my car and, when a pair of little owls called to each other softly down the valley, I cried.

Some weeks after the funeral I received a bulky package from Flora’s solicitor. It contained thick foolscap notebooks and a memory stick, the patchwork she’d stitched together during her last years in and out of hospital. The accompanying letter read:

Dear Iain

Rilke’s Torso of Apollo notwithstanding, it’s too late to ‘change your life’, even if you really want to. As I’m sure you realise, your circumstances preclude that as an option. You just have to stay with the trouble, follow such threads as you can, and wait attentively on the flow of your Borders work, rather than letting all that go. Perhaps you also need to ask yourself what really lies behind all the ‘deep mapping’ you’ve done up here? I’ve enjoyed our exchanges and recent attempt to develop work together. (Maybe, I know, so as not to speak of other things). So, what you’ve got here is possible material for you to work with, perhaps to finish what you started in terms of your Borders work, as well as something of what we’d only just begun together?

I’ll explain what lies behind what I’m sending you.

Long ago I read Joan Didion’s ‘On Keeping a Notebook’ and it stayed with me. She’s not very flattering about people who, like herself, keep private notebooks, but I’ve done it anyway. She sees us as a breed apart, lonely re-arrangers of events, somehow always anxious and dissatisfied, maybe with longstanding resentments or a sense of loss. She rightly says that keeping such notebooks is not about having an accurate record of what you’ve been doing or thinking, not about ‘the facts’. It’s about our knowing in our hearts that we all too quickly forget things we want to believe we’ll always remember. The places where we had experiences that mattered deeply. The people who loved us and those who betrayed us. The secrets we whispered to the first and the insults we wanted to hurl at the second. We keep notebooks because we’re frightened that we’ll forget the sub-text to our own stories; what we once were and, along with that, the thickness and richness of the world. My notebooks are a prophylactic, a way of combating my fear of this illness emptying me out, leaving me rootless and adrift in a shrinking present; fear of sailing without the proper ballast that our past provides.

Nobody wants to sail that last voyage without that ballast.

When she wrote that essay, Joan Didion knew she had already lost touch with some of the people she used to be. With her teenage self and her early transgressions. (She could remember the scenes, but could not see herself as part of them, or reconstruct the conversations.) Also with an older, more troubling self, one full of complaints and stories she did not want to hear again, someone who both saddened and angered her, a ghost who kept returning in a troubling and unfocused way precisely because she wanted to forget her.

My keeping notebooks was, like hers, a way to stay in touch with the life that always exceeds what we can call ‘mine’, with a world and all that is intimately bound into it, all the kith and kin. To stay in touch ‘unto death’.

Apologies for my hand-writing and the rambling nature of it all. That’s in part the consequence of the material involved, of a mind with a tendency to wander and lately, no doubt, of the drugs they’ve had me on. What I’m sending you is also, perhaps, a useful counterpoint to all that scholarly plundering and sifting you did for your books. My ‘heart work’ to your ‘head work’, if you like.

I am of course the least reliable witness possible to all these lives inseparable from my own, but I hope you’ll find time to make something of all this. For your sake, not mine. And I hope that if I (we?) haunt you, it will be in the kindest of ways.

With my love, as always

Flora.

Towards the head of the Jedwater.

Years before, Flora had initiated our friendship with the following email

Dear Dr. Biggs,

Please excuse my contacting you out of the blue like this. It’s about ‘Alison Oliver’ in your ‘8 Lost Songs’. We were very close as children and I feel you should know what really happened to her.

When I knew her, she wasn’t Alison Oliver but ‘Cat’ (Margaret Catherine) Douglas. She only became ‘Alison Oliver’ when she returned from France to work as a singer and fiddler. Nor was she ‘Canadian of Scottish decent’. Her father, Alistair, was an accountant born near Jedburgh, her mother Maria was half French, half Polish. (Her Polish diplomat grandfather married the daughter of impoverished French aristocrats and Cat’s mother never let her forget that blue blood). Nor did she simply disappear into thin air after the fire. She died a few years later in very sad circumstances.

When she dropped out of university in France Cat broke off contact with her parents and, unbeknownst to any of her childhood friends, came back here to the Borders. She supplemented her tiny income from playing and singing by waitressing and, after the fire, started living with a music promoter who was eventually jailed for dealing heroin. She died of a heroin overdose.

She was reported missing by a waitress she worked with when she didn’t turn up for work three days in a row. Then a walker found a body below the cliff path on the Northumbrian coast, just up the coast from Rumbling Kern. She’d taken a bus north, then walked to the sea. She was two months pregnant. I discovered all this because the waitress friend remembered Cat talking about me and the police then found my address in an old diary among her things.

Cat was well able to invent those songs. She knew all the old ballads inside out and had studied ethnomusicology for two years at university. She had walked all over the Southdean area too and knew a lot about its history. She used to visit cousins and they’d go on long hikes with an older family friend, a local historian and amateur archaeologist.

As you can probably imagine, it was horribly odd coming across ‘8 Lost Songs’. Anyway, I feel you should know about ‘Alison’.

Yours sincerely,

Flora Buchan.

I didn’t know how to respond to this email, which threw a different light on the work A. and I had undertaken together. I sent Flora a polite reply with my condolences for the loss of her friend. I also apologised for what might well seem to her the rather cavalier approach we had unknowingly adopted, given what turned out to be a far more tragic series of events than we had supposed. A week or so later she sent me a kind and insightful reply. That in turn prompted an irregular correspondence that, with time, became the friendship that underwrites this book.

Sarah Aitcheson wearing the Flora / Faun / Laura mask