NB – For a review of the conference at which this paper was presented see Locating the Gothic Conference and Festival: a South African Review (17 Nov 2014) by Miss Esthie Hugo.

I have just attended Locating the Gothic http://locatingthegothic.weebly.com, a very rich and wonderful interweaving of a two day academic conference and a wide range of related Gothic events, all taking place in the city of Limerick. This was organised with great flair, warmth, and efficiency by Maria Beville (Mary Immaculate College, UL) and Tracy Fahey (Limerick School of Art and Design, LIT) and allowed me to hear, meet, and talk with, a fascinating variety of very friendly and well-informed ‘Gothically-minded’ people from all over the world. I particularly enjoyed Tabish Khair’s thoughtful and compassionate paper The Significance of the Scream: Otherness in Post-Colonial and Gothic Fiction, my various conversations with Aurora Pineiro (who teaches at the National University of Mexico), and with others far too numerous to mention.

As a result it’s now only too clear to me that the field of the Gothic is much broader, more nuanced, and more deeply engaged in present and everyday issues than, in my ignorance, I had assumed. Before I went to Limerick it would never have crossed my mind that I would learn, for example, about the ways in which the trade in human organs – an increasing part of the economics of the new, post-aparteid South Africa – finds a queasy resonance in a knowing punk video for the ‘Gothic’ rap rave crew ‘Die Antwoord’. (This via Esthie Hugo’s informative and rather wonderfully titled paper ‘Hide and Sick: Gothic Pop Culture in the Contemporary South African Moment’).

I was particularly pleased to be able to chair a panel on Psychogeography and Visual Culture, which consisted of three very interesting talks on their own projects by Irish artist/educators Paul Tarpey, Martina Cleary, and Marilyn Lennon. This also gave me a chance to meet and talk with them about their work. I was at the conference to gave a plenary presentation and I’ve posted the text of this in italic below. It’s pretty much ‘as delivered’ (that’s to say without images, many references, etc.).

Anyone interested in the reasoning that fed into this presentation, or in search of a bibliography that at least in part relates to it, should look at the post Acting Elsewhere and Otherwise.

Mapping Spectral Traces: notes from, and on, a Debatable Land; Or: (Re)Locating the Gothic?

I’d like to begin by thanking Maria and Tracy for inviting me to give this presentation. The Gothic is not my field, so I’m particularly honoured to be speaking here.

Much of my work revolves around ‘deep mapping’, which uses a variety of creative practices to reimagine what might be called ‘the cartographic impulse’ from a perspective not unlike that of Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. My concern with the Gothic is via an interest in spectral traces, particularly as these relate to the re-emergence of animism. Deep mapping has to attend to the spectral element in place. In a paper called Spectral traces: photography, futurity and landscape, the Scottish artist Gina Wall draws on Derrida to note that in the particular, often uncanny, places she photographs (I quote) : “there is a strong sense of overlay of time”, so that the living present is “‘secretly unhinged’ from itself, “allowing other temporalities to leak through”. She reminds us that this challenge to exclusive notions of the present relates to Derrida’s concern with our responsibility towards ghosts. She adds that photographs – and by implication other images – can be both “spectral and futural”. They can, she argues, become “revenant” – “begin by coming back”. Hence my interest in the Gothic.

I see the Gothic as the trace of a psychosocial fault-line – the manifestation of a particular historical episode in the plate tectonics of our culture. Such manifestations inevitably slowly fade when the epicentre of psychosocial tension moves elsewhere. So there’s an implicit question behind this presentation: ‘Have the tensions that brought the Gothic into being now shifted elsewhere’? Or, put this question rather differently: “How does the Gothic relate to the Dark Mountain Project http://dark-mountain.net ; to the US military employing Max Brooks – author of the zombie novel World War Z – to script disaster simulations for military training purposes; or to prints by the Japanese artists Toshio Saeki and Yamamoto Takato? While the Gothic is clearly a major element in contemporary culture, should we understand this as an aftershock? Is the energy that originally animated the Gothic now working elsewhere – perhaps driving the appearance of neo-animism and the lifeworld as polyverse? Or is the Gothic now both spectral and futural?

I’m going to focus on two of the Gothic’s edgelands – one pre-Gothic and one contemporary. The first is vernacular, liminal and part of the material from which the Gothic emerged. I’ve explored it via a deep mapping project called Debatable Lands that drew on micro-histories and ethnographies related to an archaic vernacular, quasi-animistic, Scottish mentality. I came to the second edgeland through contingency and genetic happenstance. I’ll describe these two edgelands later.

What’s useful about the Debateable Lands project in this present context is that it moved back and forth across a fault-line identified by Isabelle Stengers in her 2012 article Reclaiming Animism http://www.e-flux.com/journal/reclaiming-animism/. This, as I understand it, is the divide between the progressive rationality of a modernity rooted in the secularized monotheism of the Enlightenment and, over against that, all it regarded as other. Not just Christian metaphysics but all those lived realities that make polytheism a “distinct mode of thought and of universal organisation”. Seen from Stengers’ perspective, the Gothic appears to me as a Debatable Land. (Historically the Debatable Land was a disputed territory straddling the English/Scottish Border north east of Carlisle. It included an Elizabethan earthwork – Scot’s Dyke – and for some 300 years it was perhaps the most dangerous place in Britain).

The first of my two edgelands is the quasi-pagan Scottish vernacular mentality that left traces in testimony from witch trails and in the old ‘supernatural’ Border ballads so important to James Hogg and Walter Scott. Drawing on authors like Carlo Ginzburg and Emma Wilby, I understand this mentality as inhabiting a polyverse that carried traces of an earlier, Pan-European animism. What’s significant about this mentality is that it acknowledges a messier, darker, less rationalized lifeworld than either late medieval Christianity or modernity. I’m interested in it because I think it evokes and addresses the same messy ambiguities that we find in the best Gothic art, albeit on somewhat different terms.

I have explored spectral traces of this mentality – this and the next slide indicate something of the processes involved – so as to stage a haunting.

I want to haunt the contemporary neo-animist theory of Felix Guattari and the anthropologist Tim Ingold. Like a revenant returning to warn loved ones in an old Border ballad, I want to remind neo-animist theory that loss and pain are central to human identity. So this haunting is intended as a prophylactic against what Barbara Ehrenrich calls our ‘Smile or Die’ culture and draws on my experience of a second edgeland. This is a limbo or non-space created by powerful authority figures who terrorize a vulnerable, marginalized group of people – a situation that I’m going to suggest is a literal enactment of Gothic terror. The people in this group suffer from chronic Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – ME for short.

This presentation is in four stages. I’ll begin with some background. I’ll then focus on my second edgeland, its relationship to the Gothic, and its relevance here. Following that I’ll locate and describe my first, neo-pagan, edgeland – in part to explain my linking Stengers’ thoughts on animism to my sense of the Gothic as a fault-line. Finally, I’ll turn to the question of whether a re-mapping of the Gothic would now be beneficial. What I’m going to say – and the images of my own work I’ll show – flow in large part from my Debateable Lands project. This started as an exploration of the supernatural Borders ballad Tam Lin and of specific locations on the English/Scottish Borders I associate with it. Later it expanded into an examination of site-specific memory, liminality and metamorphosis. I’ll show you some material from this project, but won’t say much about individual works since these are not my focus here.

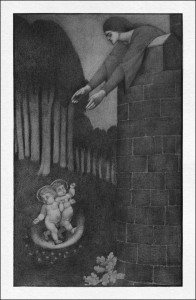

I’ll also show you images by the painter Paula Rego. These I take to be located firmly on one side of Isabelle Stengers’ divide. As a child in Portugal Paula sat under her parents’ kitchen table and absorbed peasant proverbs and folk tales, material with the same ancestry as my Borders edgeland. Refracted through memory and imagination, this material still pervade her work. Unlike Paula I’ve no direct, visceral, access to that ancient vernacular mentality. Instead I came to it by researching Tam Lin and the micro-histories and psycho-geographies that flow through and from it. That in turn took me to studies of Scottish witch trial testimony. But despite differences between Paula Rego’s approach and my own, I see them as complementary, not as opposed.

One issue here is whether it’s possible to learn from the mentality underpinning Tam Lin – its tenacity, dark humour, plain speaking, and canny attention to an uncanny world. And, if so, whether attending to that mentality can help us ground and re-orient contemporary neo-animist theory so as to better understand and live with the uncertainties of our own more-than-human polyverse? Can it help engender the qualities necessary to living with a life-world that is both the object of scientific study and what the phenomenologist and magician David Abram calls (I quote): “a spontaneous, playful, and dangerous mystery in which we participate”.

So my haunting aims to be a reminding of the kind enacted by the three revenant sons in the ballad The Wife Of Usher’s Well. Haunting is the appropriate term here because neo-animist theory moves too quickly over issues of human pain and loss, its forgetfulness a symptom of what Stengers sees as tradition of analytical theorizing that’s contaminated by “a poisoned milieu”. One that, to use her own analogy, assumes it “knows better” than both the witch and the witch hunter, so that its adherents become heir to the particular authority assumed by the witch hunter. The production, consumption, and use of this hyper-analytical discourse remains framed by the now naturalized presuppositions on which that particular authority depends. As such it’s blind to the lifeworld as polyverse.

I see our dilemma as follows. We need neo-animist theory to help deconstruct mono-ideational belief systems – scientism, economic fundamentalism, analytical reductivism, or theological fundamentalisms claiming to be derived from the Religions of the Book. But, as Stengers indicates, such theory is itself ultimately the product of practices and traditions situated on the colonialist’s side of the divide. The side that characterized ‘others’ as animists and is itself characterized by obedience to the moral imperative: ‘thou shalt not regress’. So we remain in thrall to a discursive realpolitik predicated on possessive individualism, on unsustainable notions of techno-economic progress, and on the ancient, pervasive fear of cognitive dissonances inevitable in a lifeworld experienced as polyverse. Historically, Christianity’s ability to displace paganism lay in large part in managing that fear, converting it to an engine of salvation. But as Christianity as an explanatory system started to loose its authority, that fear had to be reframed – an historical process that first initiated the Gothic and may now have run its course, or so Marina Warner suggests.

As I’ve said, I’m interested in the imaginal world of Paula Rego’s work because much of it is located on the ‘wrong’ side of Stengers’ divide. Like any imaginal artist, she is perfectly happy to regress. She understands that ongoing metamorphosis is inseparable from imaginal work. My own approach is embedded in creative in-disciplinary research and is inflected by the assumption that borders, divides, boundaries both separate and join distinct territories. The Debatable Lands project deliberately crosses and re-crosses boundaries as an act of translation or bridging. It moves back and forth, happily schizophrenic – sometimes involving ‘regressive’ imaginal making and sometimes observantly participating in contemporary research and theorizing – all in the hope of translating between – bridging – the two sides of Stengers’ divide.That’s why I see Paula Rego’s approach and my own as complementary – not opposed.

I hope something of the spirit of that bridging activity is evoked by these images.I also hope it’s clear why the project needed a psychosocial framework not aligned to a ‘progressive’, colonizing, scientism – not bent on reducing everything that exists to objective, rational knowledge. That alternative framework is a post-Jungian, ‘polytheistic’ social psychology. An observation by James Hillman from 1992 should indicate the relevance of that approach.

“We do not die alone. We join ancestors, and all the little people, the multiple souls who inhabit our nightworld of dreams, the complexes we speak with, the invisible guests who pass through our lives, bringing the gifts of urges and terrors, tender sighs, sudden ideas – they are with us all along, those angels, those demons”. (“Recovery” (1992 p. 127).

This statement may appear deeply alien in a culture of hyper-individualism but, like this group portrait of five generations of the More family, is entirely consistent with Gina Wall’s reading of Derrida’s “unhinged” and revenant present.

If I think Marina Warner may be right in suggesting that the conditions that gave rise to the Gothic no longer apply, why am I concerned to reconsider the spaces of the Gothic? The simple answer is that my desire to haunt neo-animist theory is therapeutic –animated by questions about how we best inhabit our life-world as polyverse. And my only real justification for speaking here is that I experience the same therapeutic desire in certain contemporary ‘Gothic’ works. I find it in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Diane Settlefield’s The Thirteenth Tale,Margo Lanagan’s Singing My Sister Down; in audio-visual work by Catherine Sullivan; in Davina Kirkpatrick’s collaborative, site-specific, mourning performances; in Cecelia Mandrile’s reworking of the ‘Trouble Dolls’ of her South American childhood; and in songs by Lal Waterson, The Handsome Family, Emily Portman, Alasdair Roberts, and other singer/musicians who draw on the supernatural Borders ballads tradition. It seems to me that, along with specifically Gothic elements, these works vividly acknowledge that our lifeworld is multi-stranded and conflicted; that it always both exceeds and falls short of any categorical mapping predicated on a mono-ideational explanatory system. And that it’s not enough to smile, or to see everything we can’t smile about as an opportunity to build up the resilience of our personal egos. Given the terrible eco-social and intra-psychic damage inflicted by mono-ideational systems, I hope my suggestion that we now need to think of our lifeworlds as polyverses won’t appear too outlandish.

Before I describe my second edgeland I need to ask how you understand Angela Carter’s claim that: “we live in Gothic times”.

I ask this because my second edgeland is, at least to my mind, the product of a literal enactment of the Gothic. It’s a zone marked by the terror imposed by people in authority onto others already rendered helpless by chronic illness. This is the Gothic zone inhabited by people suffering with ME, and by their families and carers. A zone created by the medical and psychiatric Establishments that neglects and abuses them and that is contested by the same therapeutic impulse that I find in aspects of the Gothic.

I think the award-winning film Voices from the Shadows http://voicesfromtheshadowsfilm.co.uk is animated by that same impulse. By the need to give a face to – and so to face – a situation that is almost unbelievably painful or terrifying. In the case of ME this is abuse – by authority figures whose actions exhibit the exact antithesis of the qualities they publically claim to embody – of chronically sick individuals without power. In extreme cases these authority figures threaten patients with forcible hospitalization or with being sectioned and placed in psychiatric units. They threaten this because patients, or their carers, refuse treatments that they know will exacerbate an already chronic illness. And of course individuals have died or taken their own lives when these threats are carried out.

The Gothic nature of the terror here lies in part in a grotesque but deeply institutionalized assumption. Namely that nothing ME sufferers say about their illness can be trusted. Their experience, self-understanding, their entire identity, is regularly dismissed out of hand by those professionally empowered to determine their treatment. Any articulation of their own reality that is at odds with the official view of their illness is, all too often, taken as evidence of a pathological desire to deceive, a willful attempt to ‘stay sick’.

So I want to argue that ME sufferers live not only in Gothic times but also in a Gothic zone. They are trapped in this liminal zone and, as a consequence, constantly threated with ‘zombification’ in the sense of being condemned to a kind of living death. Threatened not simply by the chronic nature of the illness itself – as if that were not bad enough – but also by doctors, social services employees, psychologists, the realpolitik of academic research, and the fiscal policies of politicians. ME sufferers are subject to what is – paraphrasing Robert Miles on the Gothic – a process of violent deracination. They’re dispossessed in their identities, bodies and homes. Many are suspended, perhaps permanently, in a deeply frightening condition of violent personal and social rupture and dislocation – one that’s always, horribly, threatening to get worse.

My contention then is that ME sufferers – and of course innumerable others who suffer similar socially sanctioned abuse and neglect – literally live out, on a daily basis,the horror epitomized by a strand within the Gothic. This strand embodies an element of institutionalised sadism within our social system. Sadism animated by fear of cognitive dissonances that cannot be resolved or controlled by the professional authority of those who enact it. And behind this fear is the refusal to acknowledge a failure to progress, a failure to master disease. Ultimately this is a deeper fear – of regression, of the lifeworld as polyverse and, by implication, that Stengers’ divide is wrongly located, that the line between ‘progress’ and ‘regression’ has been wrongly drawn. So there’s a question here. Does all this need to be remapped, both in the context of polytheism as a distinct mode of thought and universal organisation, and of the presence of spectral and futural in the present as evoked by Derrida.

I want to suggest that paying closer attention to the two edgelands I’ve referred to might assist us to re-negotiate or translate across Stengers’ divide. It might strengthen our impulse to use image, the performative and text – both professionally and in day-to-day life – to move more freely back and forth across that divide. Why? So as to give a face to – to help us face – aspects of human suffering denied articulation and authenticity by our mono-ideational, single-minded concept of social evolution – of absurdities like ‘sustainable development’ – and the all-too-often sadistic psychosocial impulses these produces.

Notwithstanding claims from the progressive side of that divide, our world is still saturated with acute and terrible suffering – suffering that’s often denied articulation, subject to social repression, forgetting, marginalization or denial. Perhaps this suffering – and the cognitive dissonances that it produces – can only be faced, only find a face, in the ambiguous, messy space between fact and fiction, image and data, regression and progression. The liminal fictive worlds that emerge from that space often appear ‘unnatural’. In the case of Toni Morrison’s Beloved this ‘unnaturalness’ includes horrific violence, infanticide, bestiality, and haunting by a being part poltergeist, part revenant, part succubus; yet also and always still, somehow, Beloved. The practical issue here is, then, how to articulate all this through forms of telling or showing that gives horror a knowable form without explaining it away – and as such both allows and requires us to face that horror.

It’s just this need to ‘face’ horror that Nigel Clark calls for in his book Inhuman Nature: Sociable Life on a Dynamic Planet. Suggestively, in the context of my first edgeland, Clarke proposes that: “what goes by the name of ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ may be as much about coping with loss and suffering as it is about transmitting practical advice”. Acknowledging the reality of that horror is central both to our ability to cope and to the space I’m trying to evoke here – a space that borders both the Gothic and the polyverse of Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies – a space that is, psychosocially speaking, the other to our ‘smile or die’ culture.

In Fantastic Metamorphoses, Other Worlds (2001) Marina Warner identified a major shift in contemporary fiction, claiming that: “the Christian supernatural, with its terror of pagan concepts of metamorphosis, no longer obtains”. Instead, she suggests, we are offered: “… the growing fallout from such concepts as the subliminal self, with its connections to spirit voyaging, to revenants, and teleporting souls, to animism and metempsychosis, to a vision of personal survival through dispersed memory, in life and in death, rather than Freud’s unconscious, and its hopes for potential individual integration”. I see this shift as anticipated by the understanding evident in my early quotation from James Hillman. From my perspective what she is identifying is a shift away from the historical tension between the monotheistic presuppositions of the Christian supernatural and all that’s Other to it – the tension that located the Gothic as a Debatable Land. And it seems to me that this shift might require those engaged with the Gothic to reformulate its territory.

I happen to think that Warner’s observation is belated. The new relationships between terror and identity central to our emerging psychosocial situation were already apparent in the 1970s, in Hillman’s work and in novels like Ursula Le Guin’s 1974 double award-winning The Dispossessed. I’ll now suggest a historical context for Warner’s argument, one that relates to my first edgeland.

Pieter Bruegal the Elder’s painting Netherlandish Proverbs is an early example of visual art as proto-ethnography. Itdocuments some one hundred idioms and aphorisms of Flemish peasant life and is sometimes seen as a critical comment on human stupidity and foolishness. If that’s the case, it’s a contribution to the sixteenth century’s systematic creation of intellectual distance between itself and the old vernacular culture that informed my first edgeland – the same process by which Scottish Calvinism violently differentiated itself from an older, quasi-pagan, vernacular culture.

But Bruegal’s late works – including The Corn Harvest of 1565– suggest that he was more ambivalent than such a reading suggests. So it may not be entirely fortuitous that, 435 years after this work was painted, the anthropologist Tim Ingold used it to help him articulate the neo-animist concept of taskscape, a stepping-stone to a mycelial thinking that parallels that of Deleuze and Guattari. Ingold’s neo-animism is implicit in his understanding that physical locations are a complex meshscape: “a polyrhythmic composition of processes whose pulse varies from the erratic flutter of leaves to the measured drift and clash of tectonic plates”; with the result that we are co-constituted by “a tangle of interlaced trails, continually ravelling here and unravelling there”.

His casual use of the word unravelling is, for me, indicative of the forgetfulness of neo-animist theory. Forgetfulness of the human price paid for inhabiting a polyverse – all those messy paradoxes, cognitive dissonances, and painful ‘unravellings’ that inevitably flow from the politics of our eco-social situation – not to mention our mortality. In short, it forgets the lived, existential reality of that word ‘unravelling’ – the reality acknowledged by a character in Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed when he insists that human solidarity “begins in shared pain”. But I’m running ahead of myself.

In 1662 Isobel Gowdie – who lived in the Scottish hamlet of Lochloy some twenty miles east of Inverness – was accused of witchcraft, arrested, and rigorously interrogated. Her extraordinarily detailed testimony provides the basis for Emma Wilby’s book The Visions of Isobel Gowdie: Magic, Witchcraft and Dark Shamanism in Seventeenth Century Scotland. Of all attempts to understand such testimony, this book gives perhaps the most comprehensive sense of the lifeworld of the accused as a polyverse, the same vernacular polyverse that left its trace in the supernatural Border ballads. It seems almost certain that Isobel experienced her lifeworld as perpetually dogged by cognitive dissonances, by inexplicable levels of human violence, by the chronic uncertainties of the natural world and, perhaps most difficult for her to comprehend, by the all-pervasive social fallout of recent and radical metaphysical regime change.

By the 1660s the Scottish land-owning classes had largely internalised a strictly dualistic Calvinism. By and large Isobel and her peasant neighbours had not. Their lifeworld continued to be shaped by a multitude of forces, all interwoven and some antagonistic. This polyverse was tensioned between individual lives and the natural rhythms of the land, the authority of both human and divine law, the power of human desire categorized as demonic temptation; the inexplicable patterning of fate governed by the planets and stars; and the various powers inherent in their local, vernacular, emotional geography. These included wise women and their familiars, revenants, wizards, collective dreaming, sites associated with popular Catholic belief, and of course ‘the good neighbours’ – the elves or fairies ruled over by The Dame of the Fine Green Kirtle or Queen of Elphame. In consequence Isobel’s lifeworld as polyverse was radically at odds with the strictly monotheistic universe of Calvin.

So I want to suggest that, in certain respects, her lifeworld was actually closer to the dense webs of complex interdependences that determine our current ecological, economic, and psycho-cultural conditions than to Calvinism – if only in its structural complexity and the radical uncertainty regarding the exact relationship between particular causes and effects.

Hypothetically of course the Calvinist God sat spider-like right in the centre of Isobel’s polyverse, governing all its aspects. But in practice she and most of her neighbours lived uneasily, and often fearfully, at the convergence of a constellation of fluctuating cultural, natural, and supernatural forces ambiguously related to that God – if related at all. Unsurprisingly then, it took the full dogmatic violence of the Puritan revolution in Scotland to suppress that polyverse and the old ballads that tacitly perpetuated its values. It declared them both illegal and damnable. Yet despite that violent reframing, the supernatural ballads and their offspring – Gothic or otherwise – still haunt us. And I think we need them to do so if we are to find forms of understanding, and of creative praxis, to help us face our emergent polyverse and so our uncertain future.

Isobel’s way of inhabiting her profoundly uncertain polyverse offered her the support of powerful psychosocial beliefs and rituals, strange as these now seem to us. These helped her face and cope with a world that constantly and terrifyingly threatened to unravel before her eyes. My hope is that aspects of the Gothic at its best can still do something similar for neo-animist theorizing, helping it become a thick description of our polyverse by enabling our traveling back and forth across Isabelle Stengers’ divide.

This is why I think we need to revisit the parallels between Isabel Gowdie’s polyverse and our own. Between, for example, the suppression of her vernacular culture and the sadistic terror imposed on powerless contemporary social groups by those who act in the name of a supposedly benign science or of civil society. But we also need to explore less obvious matters. Why, for example, do the animal transformations in Tam Lin still evoke a certain psychic latency that resists the single-minded conceptions of the status quo? Does this relate to the wonder that Jane Bennett identifies with a child’s sense of itself as emerging out of an over-rich field of protean forces and materials, only some of which are tapped by its current, human, form? A sensing she links to Deleuze and Guattari’s interest in the childhood game of becoming-animal, becoming-otherwise. And what human need is served when children, animists, and the imaginally engaged access a polyverse constantly in play? But again I’m digressing.

My concern here is not with Bennett’s celebration of neo-pagan enchantment – however important that may be. It’s with our culture’s growing inability to face, and give value to, unravellings – those painful elements in human life that our ‘Smile or Die’ culture actively distorts or denies. Painful elements that, I want to suggest, may require a re-mapping of the Gothic, one that can support coping strategies that enable us to face, rather than belittle, deny, privatize or otherwise exploit the human pain and suffering that grounds our commonality. This would be in line with James Hillman and David Abram’s insistence that we must address the ‘anesthetized numbness’ basic to our culture – which of course is where Bennett’s neo-pagan enchantment comes in. Perhaps only then can we realistically face powers that exceed all our attempts to control them – along with the grief and suffering they inevitably bring us.

Any such remapping of the Gothic would relate to David Abram’s claim that a new environmental ethics will appear: “not primarily through the logical elucidation of new philosophical principles and legislative strictures, but through a renewed attentiveness”. Attentiveness, that is, to the “perceptual dimension that underlies all our logics, through a rejuvenation of our carnal, sensorial empathy with the living land that sustains us”. I think the Gothic is central here because that carnal, sensorial empathy tends to be experienced in a temporal present that, as Gina Wall reminds us, needs to include traces of spectral “unravelings” – both of the consequences of the wild destructiveness of earthquakes, volcanoes, storm surges, floods, and tsunamis, and of the chronic abuses that cause man-made terror and disaster.

In drawing this presentation to an end I’ll take my cue from Marina Warner and suggest – despite being a trespasser here – that the re-emergence of the lifeworld as polyverse may have implications for how you articulate or map what’s vital in the Gothic, given that its mass-market version is now a ubiquitous aspect of the global culture industry.

So I want to ask whether the psychosocial value of the Gothic has been diluted, even perverted, in the service of mass entertainment? While films like George Romero’s 1978 Dawn of the Dead could once be seen as a biting criticism of consumer culture, is the figure of the zombie now co-opted to feed the pathology of murderous personal entitlement that Elias Canetti so succinctly identified in his discussion of the ‘survivor’ in Crowds and Power?

I would argue that Paula Rego’s response to the failure of the abortion referendum in Portugal enacted in these images evokes an empathy once central to aspects of the Gothic. They refer us to current enactments of a literally Gothic horror in our own backyard. So I want to suggest it’s not enough to note, as Marina Warner has done, that the figure of the zombie thrives today because: “work turns people into zombies; other people turn people into zombies; life does it (so do committees)”.

I’ve tried to suggest ways in which the Gothic may continue to be relevant to our need to find, and continually renew, ways to facing, of coping with, suffering, horror, cruelty, loss, grief and death. Facing these means just that – finding ways to give them a face familiar enough to identify them for what they are without trivializing the fact that they remain on the border of the unspeakable. Of course this doesn’t mean simply accepting the horror that Beloved or Voices from the Shadows show us. What it does mean is that we will need to acknowledge an ethical baseline grounded in “shared pain” if we are to engage fully with our emergent polyverse. Shared pain leads to shared coping strategies – to the sense of common concern denied by Canetti’s survivor on the basis of a pathological, indeed ultimately murderous, sense of personal entitlement.

Speaking personally,I have to accept that I can do relatively little to facilitate a cure for my daughter’s ME, or even to seriously mitigate the difficulties she will inevitably face when my wife and I – her carers – die. While I was putting together this presentation we were getting reports of a young German woman with ME slowly dying as a result of being sectioned. This situation is the direct result of the arrogance and ignorance of the medical establishment and judiciary and of her father’s vindictiveness towards her mother. So I value any image or narrative that helps me cope with the suffering caused by my relative helplessness, my sense of disempowerment, loss and grief. Again, how we determine the balance between coping and the outrage that led our family to make Voices from the Shadows is obviously critical, but not something I can address here.

As experts on the Gothic you’re best placed to say whether it needs re-mapping. I can only suggest why that might be useful. What is clear to me is that neo-animist theory can’t generate the ecosophy Guattari rightly calls for while it forgets that re-thinking our situation is not enough. We also need a heartfelt reframing of human expectations. That reframing must enable us to see that human sufferingis not a ‘problem’ to be ‘solved’. It’s integral to the human sociability that Canetti’s pathological ‘survivor’ refuses to acknowledge. We can cope with suffering through endurance, tenderness, common courage, and kindness, but we can’t abolish it. It’s this hard fact that opens us to what Emanuel Levinas calls ‘being as vulnerability’, and it’s in this context that I ask if the Gothic needs re-mapping.

The ‘survivor mentality’ increasingly pervades our society. Those adopting it act in the belief that their lifestyle is an exclusive right – despite the misery, or indeed the extinction, of vast numbers of human and non-human beings this causes. Even given the heading that goes with this image, it may well seem unreasonable to identify the mass adoption of this mentality as the most disturbing current manifestation of Gothic horror. But consider some recent research undertaken at a prestigious US University. Using MRI scans of students’ brain activity, this shows that many students, particularly the wealthiest, react to photographs of the homeless and drug addicts as if they have stumbled on a pile of trash. In the UK we are now familiar with this mentality from the present Government’s policies on the long-term sick and very poor.

Are these groups the kind of ‘human trash’ that elements within the popular culture industry now visualize as a ‘zombie plague’ to be eliminated? I’m not qualified to answer that question. But I’ll end by suggesting that it’s just such questions that any re-mapping of the Gothic would need to address.

I’d like to acknowledge the coaching on the Gothic I received from my daughter Anna, whose breadth of reading and liveliness of mind were a great asset in helping me put this presentation together.