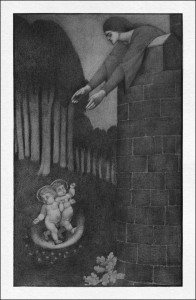

The Cruel Mother from Ballads Weird and Wonderful. Illustrator Vernon Hill.

(This is one of Vernon Hill’s many evocative visualisations of key moments in old ballads. These are some of the best visual responses to the ballads that I know of and can be found at http://spiritoftheages.com/Ballads%20Weird%20and%20Wonderful%20(1912).htm )

On Friday evening last week I attended a concert of Gothic music in Limerick called Blood and Bone. This was performed by Sionna – www.sionnasingers.com – that consists of Hannah Fehey, Femke van der Kooij, Emma Langford, Niamh O Brien and on this occasion two guests, Fr Columba McCann on organ and percussionist Dale Halvey. This was a powerful and moving performance in its own right, containing as it did pieces by Hildegard of Bingen (one of the greatest, and also most practical, of medieval visionaries) and a range of other composers from the C12th through to the C17th century (along with a fine contemporary organ improvisation for good measure). However, two of the fragments of text included in the programme also prompt me to return to a point I indirectly touched on in my presentation for the Locating the Gothic conference, namely possible inflections of the relationship between the Gothic and environmental issues, particularly as these are perceived by a group like the Dark Mountain Project.

The key link here is, I suggest, the revised 1986 edition of Peter Marris’ book Loss and Change in which notions of ‘bereavement’, ‘conservatism’, and ‘incoherence’ play a key role in relation to change. (I would disagree with Marris over what I see as his – understandable for the time – failure to recognise the importance of testimonial imagination in relation what he calls ‘the conservative in innovation’, but that’s another issue).

The first of the fragments that speak to me from Sionna’s Programme Notes is from Responsory For The Innocent by Hildegard of Bingen. The text reads: ‘Receiving blood sacrifice from earth “Angels sound harmoniously, and in praise together, but the clouds weep for their shed blood”’. This highlighting of the contrasting responses of the Angelic Powers – ‘high’ representatives of the ‘arboreally-structured’ authority of The Great Chain Of Being that reaches up to the Divinity and the ‘rhizomic’ processes of the natural world (the clouds), seems to me to pre-figure our contemporary environmental dilemma in ways that bring a Gothic colouring to environmental issues. This colouring was taken up in the penultimate piece Fuweles In The Frith.

The programme note for this reads: ‘The profound last phrase, “for best of bon and blood”, brings to mind that we as humans are like all other creatures of bone and blood, while also calling to attention the fragility of our mortal state’.

‘Birds in the wood,

The fishes in the flood

And I must go mad

Much sorrow I walk with

For beast of bone and blood’.

This sentiment reminded me at once of the wonderful quasi-pagan version of the old ballad The Cruel Mother recorded by Alasdair Roberts on his CD of traditional songs No Earthly Man. The lyrics of this version are as follows:

She leaned her back up against the thorn

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

Then she has a bonny babe born

And the lion shall be lord of all

She layed him beneath some marble stone

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

Thinking to go a maiden home

And the lion shall be lord of all

As she looked over her father’s wall

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

She saw that pretty babe playing a ball

And the lion shall be lord of all

Oh bonny babe if you were mine

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

I’d dress you in that silk so fine

And the lion shall be lord of all

Oh mother mine when I was thine

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

I didn’t see any of your silk so fine

And the lion shall be lord of all

Oh bonny babe pray tell to me

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

The sort of death I shall have to die

And the lion shall be lord of all

Seven years of fish, fish in the flood

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

Seven years of bird in the wood

And the lion shall be lord of all

Seven years of tongue to the warning bell

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

Seven years in the flames of hell

And the lion shall be lord of all

Welcome, welcome fish in the flood

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

Welcome, welcome bird in the wood

And the lion shall be lord of all

And welcome tongue to the warning bell

The sun shines down on Carlisle Wall

But God keep me from the flames of hell

And the lion shall be lord of all

What so moves me here is the protagonist of the song’’s deep empathy and identification with the worlds of natural and human danger – her willingness to accept, indeed welcome, a punishment that involves spending seven years as ‘a fish in the flood’, a ‘bird in the wood’ and a ‘tongue to the warning bell’ respectively – if this will only keep her from banishment to an unknown metaphysical realm ‘elsewhere’, will keep her ‘from the flames of hell’ central to Christian metaphysics. The resonances here with what I hope for in our contemporary Neo-animisms – which in my Limerick presentation I argued must not only insist on our need to return to just such an empathy with our given, fleshly world, but also with all its sufferings and dangers – seems to me exemplary.