Introduction

Since 1999, when I began concerning myself with what I would come to know as deep mapping, I have been vexed by the question of what role, if any, the first of Felix Guattari’s three ecologies – namely the ecology of the ‘self’ – should play in such work. That question has been deepened by the work of two recent doctoral projects that I helped to supervise: Dr. Ciara Healy-Musson’s Thin Place: An Alternative Approach to Curatorial Practice (2015) and Dr. Davina Kirkpatrick’s Grief and Loss; Living with the Presence of Absence. A Practice-based Study of Personal Grief Narratives and Participatory Projects (2016). Both, in my view, point up the inadequacy of current conceptions of the relationship between ‘self’, society, environment and the past by focusing on different aspects of our relationship to the dead.

In December 2016, I gave a presentation at the Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG) conference in Southampton entitled: ‘Hearing’ heritage: The Kirkyard of St Mary’s of the Lowes, in which I explored the possible relationship between two traditional ‘supernatural’ ballads and that abandoned Kirkyard. It is probably fair to say that it got a mixed reception. No doubt my failure to time the presentation accurately did not help but, more critically, one emphatic commentator insisted that it is simply academically inappropriate to ‘speculate’ where there is no verifiable historical record (e.g. written documentation) to support that speculation. In short, I was told that ballads can only be taken to be suggestive of a mentalité once they have been written down.

Although I don’t accept that assumption, believing with Lizanne Henderson and Edward J. Cowan that “ballads can contain factual truths not found in the often scanty records, and can contain certain emotional truths, the attitudes and reactions of the ballad-sing folk to the world around them” (Scottish Fairy Belief 2001: p. 5), I found this critique of my speculations dispiriting. (It was delivered with all the assurance of one delivering a scientific truth). What follows, however, is a reworking of that original presentation that simply ignores that ‘scientistic’ assumption. It is also made in the light of my subsequent reading of three texts: James Hillman and Sonu Shamdasani’s Lament of the Dead: Psychology after Jung’s Red Book (2013), Claude Lecouteux’s Witches, Werewolves and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages (1992, translated into English 2003) and Richard Firth Green’s Elf Queens and Holy Friars: Fairy Beliefs and the Medieval Church (2016) and attempts to address, in a limited way, the issue of the importance for those engaged in deep mapping and related activity of ‘listening to the dead’.

The updated presentation

In Archaeological Narratives and Other Ways of Telling, Mark Pluciennik argues that a more democratic approach to narrative might offer fresh opportunities to reflect on the roles and possibilities of both narrative and non‐narrative writings of archaeology. I’d want to extend his argument by linking it to Gemma Corradi Fiumara’s call that we return to a listening that attempts to recover the neglected and perhaps deeper roots of thinking. Also to the geographer Karen Till’s argument that acknowledging the historic ‘wounds’ associated with particular sites enables the memory-work needed to create healthy places, citizens and states. This, along with listening to two old Borders ballads, frames my thinking about how the The Kirkyard of St Mary’s of the Lowes might be narrated so as to evoke something of its complexities and paradoxes.

Prof. Arthur Watson – an artist, teacher, author, and the twenty-first President of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture (RSA) – has participated as a singer in the oral tradition of the Scottish Traveler community since he was fifteen. Within this oral tradition old ballads like Tam Lin have been passed down from singer to singer for many hundreds of years. Professor Watson sees that oral tradition as supported by notions of memory and authority that are the antithesis of academic thinking, in my view entirely correctly. I mention this because much of my work connected to deep or narrative mapping over almost twenty years has happened in the creative space between those two notions of what is to be taken as ‘authoritative’.

The Kirkyard of St Mary’s of the Lowes overlooks St Mary’s loch in the Scottish Borders and is situated just off the A708 between Selkirk and Moffat. It sits in the valley of the Yarrow and Ettrick Waters, a location central to a variety of ballads extending from pre-16th century ballads like Tam Lin, through to late Seventeenth Century ballads like The Battle of Philiphaugh. In short, the kirkyard in question is situated in both a physical landscape and a highly charged vernacular songscape.

This site is currently the object of two quite distinct public narratives. The first is the on-line archeological account given by the Borders Archeology Company. Although the author is careful to make it clear that his account is provisional, it tacitly evokes the objective authority of ‘fact’ as underwritten by the academic disciplines of history, archeology and etymology. This narrative begins by citing archival evidence for the existence of the now-vanished chapel in 13th century documents and works its way back in time, citing both archeological and etymological evidence to support its provisional findings. This narrative proposes that the kirk, abandoned in 1640, once stood near an earlier ‘kil’ or cell occupied by a hermit. The name ‘Lowes’ derives from the Cumbric term for a lake. Since the site was also originally located in the Cumbric diocese of Glasgow, the implication is that the cell was Cumbric in origin and may have been established as early as the 6th century. Archeological material in the surrounding landscape also suggests that the site may have had some pre-Christian significance.

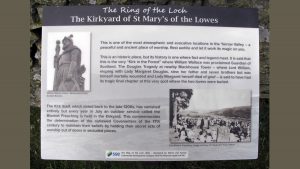

A second narrative, provided by the Etterick and Jarrow Community and Development Company, is found at the site itself. Its wording meets the needs of a Borders heritage industry catering to those people, frequently Americans, visiting the Borders in search of their roots. Archaeology doesn’t feature here. The information board is one of a set distributed around a circular walk that starts and ends at the statue of James Hogg at the head of the loch. The board presents the site as: “a peaceful and ancient place of worship”, encouraging us to “rest awhile and let its magic work on you”. It then invokes two major heritage tropes – Scots nationalism and radical Protestant dissent. In the first case by positing a link between the site and William Wallace, in the second by drawing attention to the annual Blanket Preaching in commemoration of the Covenanters held on the site. This second reference also authenticates the site as one of enacted remembrance. A further reference to a tragic romance connected to the Douglas family – still major regional landowners today – adds local colour. I’ll come back to this reference later.

What interests me is, however, absent from both these narratives.

As already mentioned, this site is situated within a songscape dominated by what are called the “supernatural” ballads, versions of which first enter the written record in the late 14th century. These are old, layered and fractured sung narratives that contain both explicitly Christian and non-Christian folk material. I’m particularly interested in the traces of the non-Christian medieval lifeworld, because they resonate with current theorizations of ‘a sensible materialism’ and of ecological concerns by thinkers such as Isabelle Stengers, Jane Bennett, Donna Haraway, and Bruno Latour. I see these traces as a basis for work with testimonial imagination that might bridge a neglected aspect of the history of the psyche, current high theory, and an emergent attitude present in contemporary popular culture. Something of this emergent attitude is implicit in two verses from the song Resurrection, by the American singer Rita Hosking.

I’ll have no rebirth but I will be in the bark of trees and the breath of air

I’ll not be in a church, but in the cells of leaves and maybe I’ll see you there.

Significantly, Hosking relates her work to the tradition of Appalachian ‘mountain music’ which, among other sources, draws on the old Borders ballads.

The valley in which St. Mary’s kirkyard sits is haunted by two ballads in particular – Dowie Dens of Yarrow and Tam Lin. Before Hogg became the public figure commemorated here, he was the shepherd grandchild of Will O’Phaup, reputedly the last man in Scotland to converse with the fairies. Which is only to say that, as a child he internalized a heterodox ontology, radically at odds with the strict monotheism of Calvinism. The land-owning and professional classes memorialised at St. Mary’s kirkyard had adopted Calvinism a century before Hogg’s birth. But some of the rural laboring class resisted Calvinism, preserving a now banned oral tradition of ballads populated by transgressive women, revenants, prophetic dreamers, and uncanny figures like Thomas the Rhymer, taken by its Queen into fairyland.

I need to clarify something at this point. There is a physical location known as “Tam Lin’s Well” in Carterhaugh Wood on the Etterick, down-stream from St Mary’s loch. Sir Walter Scott indicated, and numerous people still believe, that this is where Janet, Jennet or Lady Margaret met Tam Lin – the young grandson of the Earl of Roxbrugh who’d been abducted by the Queen of Elfland. I’ve no interest in such literalism, but neither do I see the content of the old ballads as picturesque nonsense. I hear these songs as echoing a vernacular lifeworld regarded by the Christian authorities as heretical, marginal, foolish, or otherwise unacceptable; a life-world that, in consequence, is largely absent from both the historical and archeological record. Aspects of that lifeworld are now being recovered by scholars like Emma Wilby, who analysis and contextualize material common to both the supernatural ballads and testimony given by individuals accused of witchcraft, and by students of medieval literature like Claude Lecouteux and Richard Firth Green.

The information board at the kirkyard refers to events narrated in a ballad called The Douglas Tragedy. This tells the story of the elopement of Lady Margaret Douglas, during which her lover kills her father and seven brothers, only to be mortally wounded himself. Margaret then dies of grief. The suggestion is that the lovers may have been buried in St. Mary’s kirkyard. An older ballad, the Dowie Dens of Yarrow, has a broadly similar plot but differs in being both framed and fractured by the devise of a prophetic dream. In this dream a mother and daughter learn that the daughter’s lover – a plowboy – has fought with nine local gentlemen for the right to marry her. The plowboy kills three of these men, three withdraw, and he badly wounds three more. At which point he’s stabbed from behind by the girl’s brother.

The significant qualities distinguish this ballad from The Douglas Tragedy. Characters accurately foresee a future event, class appears to be substituted for generational conflict over inheritance, and the landscape itself is treaded as a participant in the narrative. To what degree this is the case depends on how carefully the original collectors of this ballad listened to what was being sung. If what was hear was the words ‘dowie dens of Yarrow’, this is best rendered in English as ‘dismal narrow wooded valleys’. However, if what in fact was sung were the words ‘downie dens of Yarrow’, the reference is to fairy hills (Henderson & Cowan 2001: p. 9), a reading that would be supported by the remains of pre-historical remains in the area. This would suggest that, rather than the plowboy lover who has defeated nine men being treacherously killed because he comes from the wrong class, that the girl’s brother stabs him from behind because he suspects that the plowboy’s prowess comes from an uncanny source. In short, that he is either a fairy warrior or, like Tam Lin, a mortal associated with the fairies. (Of course, this second possibility does not exclude the issue of class). Both the attributes of ‘dowie’ and ‘downie’ to the landscape are consistent with a mentalité vividly represented by the opening lines of the anonymous C8th Irish ballad, Donal Og. These translate as:

It is late last night the dog was speaking of you

The snipe was speaking of you in her deep marsh

It is you are the lonely bird throughout the woods

And that you may be without a mate until you find me.

However, if we hear ‘downie’ rather than ‘dowie’, then the ballad is firmly located in a liminal landscape in which the boundaries between the day and night world of dream, the human and uncanny worlds, are acknowledged to be porous.

I want to suggest that, in addition to offering an alternative context for narrating this site, the supernatural ballads also point up an alternative approach to narrative. I’ll now elaborate on this suggestion.

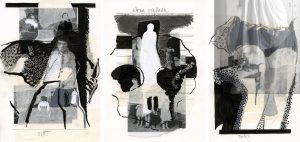

While Dowie (or Downie) Dens of Yarrow and Tam Lin clearly have a beginning, middle and end, they also give a powerful sense of being embedded within an oral tradition in which the strict linear sequence of past, present and future is disrupted by magic or prophesy. From this point of view The Douglas Tragedy and Dowie (or Downie) Dens of Yarrow reflect competing worldviews. Attempts by illustrators to visualize a supernatural ballad like Tam Lin by using a single visual style are always problematic because they are visually ‘monovocal’ in the sense that illustrators conventionally maintain stylistic consistency to evoke a sense of affective or conceptual unity. But the ballads themselves don’t employ a single narrative perspective, voice or affective register.

Instead they deploy a weave of several, sometimes mutually antagonistic, perspectives. In Tam Lin we can hear the Christian orthodoxy of the landowning class rubbing up against the beliefs of a quasi-pagan peasant culture. We hear exchanges between gendered and socially differentiated voices – human and non-human – that warn, defy, expose, mock, promise, and threaten from within a polyverse rather than a universe. This polyvocality unsettles linear narratives that are further unsettled by the fact that a ballad often share lines, or even whole verses, with others, suggesting their embeddedness within a larger mesh of stories. And then, of course, each ballad exists in multiple variations.

All these characteristics allow singers to inflect the meaning of the version they’re singing by hinting at variations that resonate in the listener’s memory. Consequently, the song’s meaning, like that of our own narrative identity, is kept open to question and contestation. Arguably, then, our experience of hearing such a ballad is creatively tensioned between an unstable linear narrative woven from multiple voices and a matrix of other – perhaps antagonistic – variations situated within the space of a larger songscape.

An alternative narrative mapping of the kirkyard of St Mary’s of the Lowes might amplify the provisional archeological information. Through listening to and referencing Tam Lin it might evoke the longevity of elements of a quasi-pagan life-world in the region and to its relationship to Cumbic or Welsh Christian theology. The Dowie (or Downie) Dens of Yarrow raises questions about the relationship between class, land ownership, multiple worlds. It might point us both to the suppression of the tripartite nature of the ‘self’ or ‘soul’ suppressed by the medieval church, and to a dubious history of Scottish nationalism personified by William Wallace. Wallace’s surname derived from the Old English “wullish”, meaning “foreigner” or “Welshman”. Where his family economic migrants from Wales or members of a Cumbric-speaking ethnic minority in Strathclyde? In either case, what does this say about the construction of a Scottish nationalism that takes him as a central figure? (There is a further possibility attached to this Welsh connection, which persisted through the speaking of Welsh in areas of the lowlands as late as the twelfth century. As Henderson and Cowan point out, this means that it is “just possible” that Southern Scots learned of the Welsh tale of Elixir’s journey into fairyland from such people and that it served as one source for Thomas Rhymer’s own journey).

The Covenanter history celebrated at the annual Blanket Preaching sits uncomfortably with the consequences of Sir David Lesly’s 1645 victory at Philiphaugh, on the bank of Ettrick Water. The Ballad of Philiphaugh which celebrates that victory makes no reference to the murder of fifty Irish Royalists who surrendered on being promised safe quarter. Nor to the killing of three hundred camp followers – mainly women and children – who were then thrown into a mass grave. Given that it was his army’s Covenanter ministers who encouraged Sir David Lesly to authorize these sectarian murders, local Covenanter history sits somewhat uneasily with the characterization of St. Mary’s kirkyard as a “peaceful and ancient place of worship”.

Conclusion

In referencing ballads to suggest possibilities for re-narrating or re-mapping this isolated Borders site, I’ve evoking multiple voices of the dead so as to thicken and contest any simply ‘factual’ account – whether archaeological (scientific) or touristic (popular). Roger Strand argues that we need to set aside the increasingly toxic culture authorised by “merely fact-minded sciences”; an authority that, he suggests, privileges the views of “merely fact-minded people” at the expense of values that contribute to “a genuine humanity”. Following Mark Pluciennik, I am suggesting that to evoke a genuinely democratic and humanitarian relationship to an archaeological (or indeed any other) site, we need to interweave multiple stories and images that invite individuals to listen out for and relish the evocation of our multiple heritages and conflicting interpretations. That can only happen if we are willing to both hear and ponder the voices and beliefs of the dead, including and perhaps particularly those ancestors who held very different views of what constituted the ‘self’, society and the environment to those that dominate our current culture.