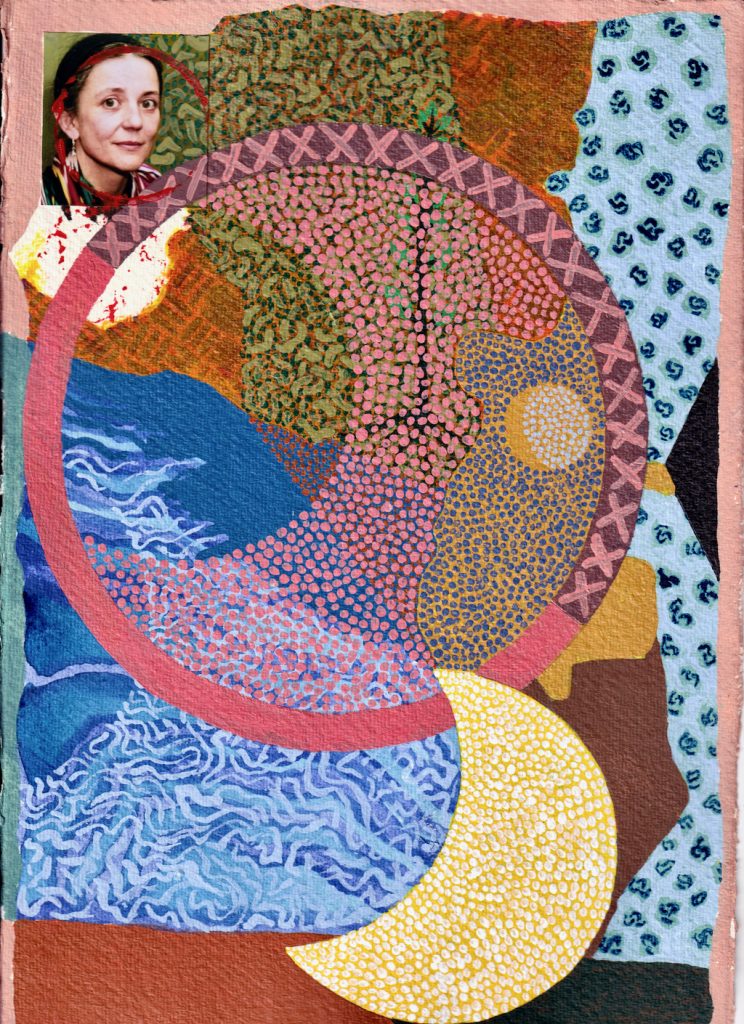

Moon, starts and sea (for Paula Meehan)

‘How does art change the world? You have to believe in these encounters having some kind of meaning’.

UB

A poem too can be a landscape.

Paula Meehan offers two understandings of what a poem “does”. She inverts Auden’s claim that poetry “makes nothing happen”, suggests that in doing nothing a poem may stop ‘something happening’, stop time, take our breath away. Like the negative space of a drawing, it allows the world to be apprehended, revealed, sets us wondering. Poetry can also evoke fellow-feeling, solidarity. Meehan writes of opening a poetry reading in Canada with a poem by the indigenous Micmac poet Rita Joe to honour both her people and the place. She did so in part because she overheard someone dismiss ‘an aging woman writing a poetry of direct experience out of her own experience’, echoing something she was ‘well used to hearing and decoding, and resisting, at home in Ireland’. (Paula Meehan (2016) Imaginary Bonnets With Real Bees In Them p. 49). Poetry then as a caring through solidarity.

The Irish-language poet Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill’s poem An Obair / My Care meditates on time and on peoples’ inhumanity, grief and care. It refers to a woman friend dying in hospital, atrocities in Algiers and Serbia, her husband’s six-day coma, and the unconcern of the tides and ongoing spring. Despite this, it’s strangely positive, speaks of a walling of the heart as firmly as the castle it names, so that the poet can answer a friend’s ‘tired question’ about her children: ‘How’s the care’? It ends:

‘… This is the task.

This is the work that is not easy’.

(Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill ‘My Care’ (trans. Bernard O’Donoghue) Northern Lights pp. 85-87).

I feel that the “hinterland” is a prime subject for poets, being the “place” that appears when we pay attention to the flowing-together of a here-and-now and an elsewhere. A place of awareness that may flair up when a skein of geese lifts and calls from the upper field above the farm before circling and wheeled north-west into the wind. When the faintly grained orange of a carrot is seen beneath the blade of the peeler. When the scent of grass newly-cut in the steep field but one above the cottage comes down on the wind that ripples the still uncut grass until it’s a sinuous green-gold sea. When we first see this year’s purple orchids lurking beside the river path, then find them again in the lea of a weathered spruce plantation high above the rough grazing land. When the mind falls silent as I write and I turn to see the dying chestnut trees across the road, the white butterfly passing beneath them, and the blue-shirted man with the small dog who appear through the gap in the wall. When their passing provokes Magnus, failed trainee guide-dog and now family pet, to exuberant barking. When glimpsing a roe doe grazing in the ragged margin between the wood and the road, or when evening sounds fade to the silence surrounding one bird singing. All of which takes place, as the news and the daily toll of roadkill remind me, under the undiscriminating eye of ever-present death. In the poem My Grandmother in the Stars Naomi Shihab Nye reminds us that:

Where we live in the world

Is never one place.

Naomi Shihab Nye (Tinder Spot: Selected Poems p. 115).

That flowing-together seems to happen when we attend, in the the here-and-now, both to that present-ness and to what haunts us – an image, a dream, a fragment of a text, or maybe a living sense of the past flickering just beneath the surface of the carefully neutral language of an archaeological report. That awareness is where Denise Levertov’s poem September 1961 takes place. Where we catch the scent of the sea on the night wind while travelling the road ‘the old great ones’ have left us to find our own way. (Denise Levertov New Selected Poems pp. 34-35). It’s where we can hope to disentangle what animated Morris Graves’ art as ‘a key to and a measure of the spiritual and the divine’, from the reductive (and embarrassed) ways what those terms refer to are taken by those who don’t see that his work is ‘open to all metaphysical systems and approaches’. (Theodore Wolff in Morris Graves: Vision of the Inner Eye p. 13).