I’m often asked why I’m not comfortable with social media. I’ve always found it hard to answer. Today, however, I found that Tara Westover had pretty much said it for me. https://speakola.com/grad/tara-westover-the-uninstagrammable-self-northeastern-2019

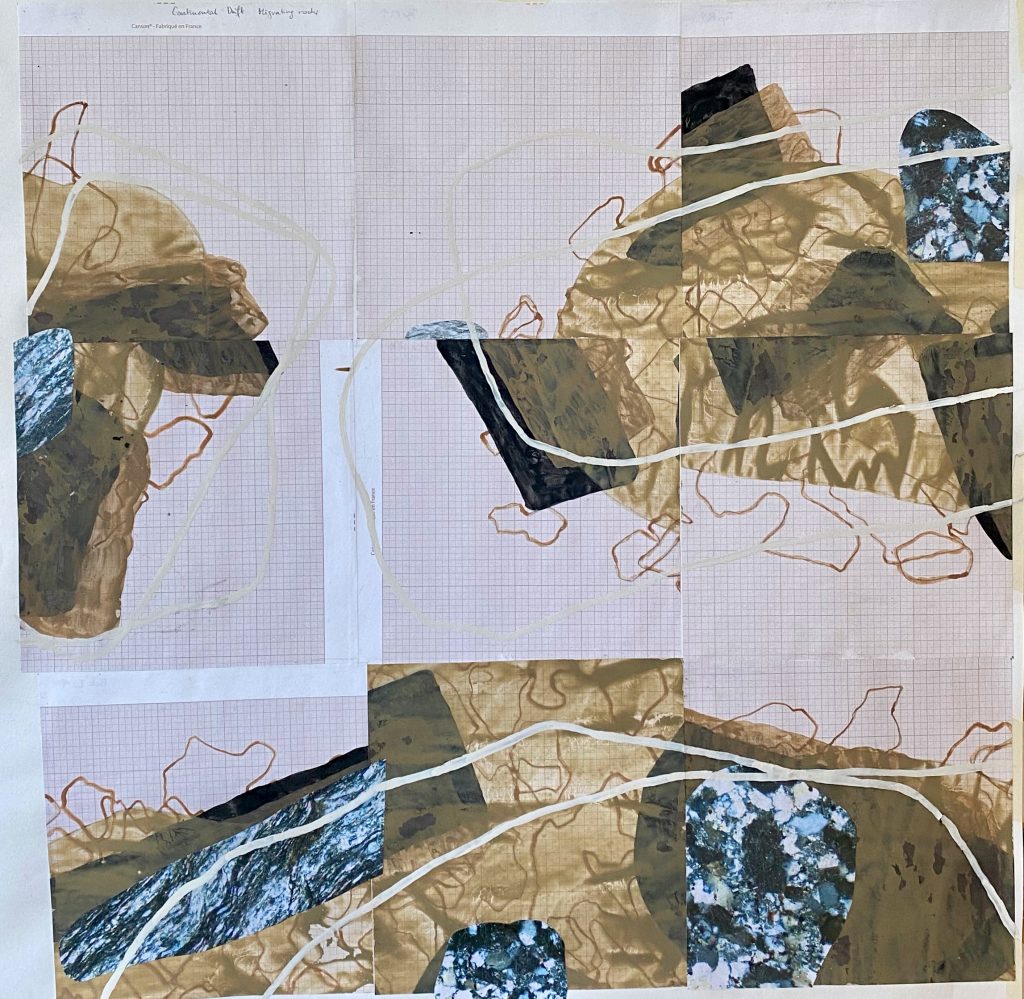

‘Concerning Convergence 1’ – A conversation between Sara Dudman, Mathilde Braddock, and myself.

Mathilde and Sara at work

Iain (S1): I thought possibly a good place to start would be if you say a little bit about Convergence, and then say what similarities and differences you see with Hanien Conradie’s work, and we can take it from there.

Sara (S3): We tend to describe Convergence as the bringing together of two quite different perspectives but with a shared affinity for the land. We come to a place from very different starting points, and what we’re both very interested in is what is our relationship with this land? How might we go about paying some devotion to that relationship, honouring it, articulating it and sharing it? Also hoping to tell a story that other people might resonate with or begin to find their own way of speaking to.

Mathilde: I’d add, for me, it’s an exploration of how to reengage or reconnect with a relationship with the land which maybe has been lost, that I haven’t been taught, or that hasn’t been exemplified for me. Also exploring what paying attention and connecting with the different parts of myself as I engage with the landscape. As a geologist by background, I have a very specific way in which I engage with landscape and with places through the scientific training I’ve had. But working with Sara, an artist, has opened my desire to connect in a more holistic, emotional and creative way with the landscape. And then there’s our joint exploration of what it means to be residents of these places and connected to these landscapes. What conversation arises between our different perspectives? And what is it about our attention to place that can help others, perhaps, to connect in new ways with these landscapes? And in the bigger picture, can it help us reconnect with a healthier relationship with the planet?

Sara: There’s a real focus for both of us, I think, on the value and importance of collecting and foraging from the place and reworking it to reimagine it. And that is very much the core of our artistic process and recognizing the value of that. We can spend time in a place and we can pay attention to it, but what we’re doing is hopefully taking that a step further forward. Our collaborative practice is very much about storytelling through that creative process.

Flat Rocks 05 (Jurassic Limestone)

Iain: I find all this very interesting because I’ve been reading Ursula Le Guin’s non-fictional writing. One piece that particularly struck me is where she talks about different languages, by which she doesn’t mean the difference between English and French, but the difference between the languages we internalise. It links very much to what Mathilde was saying about we’re educated to speak or to think in terms of authoritative discourses, whether that’s geology or even art, because art has its authoritative discourses too. Le Guin refers to that as ‘the father tongue’, because within patriarchy that’s where control and authority gets laid down. And she then talks about two other kinds of language, ‘the mother tongue’, which she sees as being much more down-to-earth, much more to do with people’s immediate experience, much more to do with people’s emotional lives. And then she talks about a third ‘unlearned language’, which she relates to poetry, to what we would relate to the visual arts. An imaginative, exploratory language that never comes to conclusions, because it’s always kind of feeling its way. And I think that, in a sense, you’re juggling those three languages and looking for ways to get them to talk to each other.

Sara: It’s interesting that you refer to the gendering of the different languages because Mathilde and I have spent the last year and a quarter now really evolving Convergence and finding its form, figuring out what convergence is, and its potential. I think we pretty quickly settled on the idea that we’re never seeking to surmount a landscape or to conquer a peak, or to do any of that kind of fairly egotistical sort of relationship with the land, about somehow owning it. I think we decided, for a number of reasons, that we were going to initiate Convergence in a single place, and just sit with, be with, almost fumble about a bit, in one place to find ourselves through being there.

Rock samples and tissue paper casts

Mathilde: We spoke about some of the masculine and feminine dimensions in the works, although I am always hesitant about the use of that binary. Initially, I remember us comparing the rigid scientific approach, in particular the chopping up of rocks and their angularity and hardness of the approach in the lab, with the much more tender, soft, experiential approach of working with the earth and the paints in the studio. We also talked about the hardness of the rock versus the flow of water, because our work is situated on a cliff-lined eroding coastline. That fluidity is ever present on the Severn Estuary, and definitely comes out in the works. And further to what you shared about Ursula Le Guin’s theory of the different languages we internalise, I think that’s a really useful perspective to bring to where we are at with Convergence now. We’ve been exploring an exchange between each of our ‘languages’. What has the juxtaposition or the coming together of these languages revealed to us? And we’re at a stage now where we want to turn that outwards, perhaps towards those spheres where people speak one language louder than another, and see if we can disrupt that a little bit. To ask questions and explore how bringing some of the other languages in can enrich our perspectives? How about, in your scientific practice, bringing in more creativity?

Flat Rock 04 (Old Red Sandstone)

Iain: I think it has to do with attitudes towards the imagination. If we think about imagination in relation to empathy, then our culture has traditionally put a very strong emphasis on care and empathy being things that women do, whereas authoritative, heroic stuff is what men do. And I agree that we have to be very careful with the gender thing. But I do think that it’s useful to understand that underlying all this there are issues of power that, in a sense, you’re pushing against, and we can’t discount that. It’s maybe not something that you would necessarily want to focus on all the time, but I was thinking of, you know, Hanien’s emphasis on where her grandmother farmed, and the fact that there is that family connection with caring for the land. And what kicked off her work in terms of the Raaswater pieces was the drying up of the river that was essential to that place. Her wanting symbolically, to find a way of reanimating, re-watering that land in a way. So there’s a kind of weaving together of strands that I’m kind of groping after in all this.

Sara: In a sense we still live in the Age of Enlightenment, in the age of ‘following the science’. Although our starting points are very different from each other, we were both born into this Western culture of scientific proof and a denial of a lot of other ways of thinking and ways of relating. I think that’s really interesting, Iain, what you said about power constructs that make other things seem subservient and irrelevant, almost. I think we’re trying to find our way back to what it is to be two women living and working and thriving in the southwest of England, where an awful lot of our indigenous relationship with the land has been discarded, and to feel our way into how we articulate that. What is that for us today? What is a healthy relationship with the land? What does that look like? You know, I was walking across a ploughed field yesterday. It was really shocking. We haven’t had any rain here for a month and it just looked bleak, bleak and scarred. Our agricultural methods … we are obviously destroying our habitat and we’re recognising that, despite whatever any scientific modelling gives us. How do we tell that story in a language that makes better sense than the scientific proof version?

Iain: I see the connection as being about a process of decolonisation; that colonisation is not something that happens just to large groups of people, where one constituency gains power over another, enslaves another, exploits another, whatever. I think we are all colonized by the dominant culture, and the dominant culture is not so much scientific as economic, and science is co-opted to serve economics, and economics is controlled by capitalist ideology. So that’s the muddle that I think we’re all in and I understand what you say about not heroically going all over the landscape, but instead finding a particular place, making a relationship with a particular place in order to get back down into the uncertainty of weather and mood and all those other things that that come into the picture when, instead of bracing yourself to get to the top of as many mountains as possible, you just decide that you’re going to be in one place and see what arises.

Working on the shore

Mathilde: I would like to respond to a few threads that have been raised by you both. For me, what is the root of the capitalist ideology you mentioned, and what we’re seeking to question and undermine with our work, is the idea of separation. That we can extract, control, and manipulate the world to our own ends because we are separate from nature, separate from the rest of the world. As Sara says, we’re now seeing that crumbling to pieces all around us. Convergence is about re-weaving ourselves with the land and perhaps engaging in a process of healing that separation. You mentioned the reanimating of the river in Hanien’s work, and of course the animacy of the places we live in has different resonances depending on where we are in the world. What might it mean to engage with the possibility of the whole planet being animate, and that we are animated with it? What might our relationships with the animate world be here, where we are situated? I think Sara was referring to the fact that in the United Kingdom, we’ve been severed from that relationship in a particular way. For me, exploring these questions through being present with the land and then working with foraged materials and creating art that speaks to these themes is part of that reanimation.

Sara: You mentioned Hanien’s Raaswater work and I have to say I find it wonderful and extraordinary, because I think it very simply but very directly says everything that needs to be said about a dry river and re-animating it, re-watering it, re-wetting it. And for me, that’s what working with the earth pigments is all about. It’s re-reworking that land in a really healthy way. It’s reusing the materiality of that place in order to tell its story. It’s really interesting, reflecting, as a visual artist sitting in this conversation, on how much our visual art forms, can speak differently. It’s a different language to the one of words that we have here. It’s more of an emotional language. And for a long time, I’ve held a belief that you know an artwork is successful if it satisfies you emotionally and intellectually at the same time, and brings curiosity and excites both of those different dimensions of experience. And that, for me, is the unique power of working with these earths and bringing that language to the front.

Mathilde: What you said there Sara has prompted a new thought about the foraging aspects of our work. We aim to only remove as much material as we need: a quiet moment on the beach sketching or taking rubbings of the rock faces; a trowel-full of mud from the estuary; a scoop of rock shards from a cliff face, which we then turn into paint in the studio. And how far that goes! A little bit of mud goes a long way towards making many paintings. There’s something there about the subversiveness of minimal extraction that has huge potential, turning our extractive culture on its head a little bit.

Foreshore: at Doniford Beach, Somerset.

Iain: What strikes me listening to you both is that, while I don’t in any way disagree with what Sara says about how the importance of the visual, which is also implicitly tactile, and so on and so forth, is that you both get very animated when you speak about the process, because you’re telling the story of what you do. And I think that’s really important. I was brought into the fine art world at a time when it really wasn’t fashionable to talk about meanings in paintings. You had Untitled 1- 97 and words were almost seen as second-class citizens. And yet when we look at the context of the work that was made under those conditions, it’s the stories that actually make sense. The critics were generating stories about what art should be, and the artists were kind of kicking that backwards and forwards as they made the work. I think there’s always the need to talk around the work. It doesn’t take away from the work, but it puts the work in a richer context. And I think that’s where I see a connection between what you’re doing and what Hanien is doing. Does that make sense?

Studio work

Sara: Yes, totally. And I think this conversation, the words in the conversation sit around the work, but there is no conversation without the work. Mathilde and I have been working in parallel for quite a few years now, about four years or so, and we just decided to take a deep breath and dive into exploring what a direct collaboration might look like. And obviously it draws on both of our rich professional practices, on what we both bring to nourish the collaboration. But something that has arisen quite recently, was Mathilde saying: ‘I’m craving time in the studio. I’m feeling starved’. I think that says so much about the whole process of working directly with, reinterpreting and reimagining, that materiality and the physicality, the viscerality of massaging the earth and making the paints and moving them around and creating layers. It was really interesting when we were looking at some of Hanien’s work on her website, she has quite a strong performative dimension to her work, which takes that a step further and physically embodies everything that she’s wanting to say. I think we feel an affinity with that and I think that for Mathilde, coming to this collaboration as an earth scientist and, within a year of actually being present in the studio and physically contributing to the art-making process, to hear her saying: ‘I’m starved. I need to be back in the studio’. That, for me, makes Convergence worth it all day long. Because I think that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to highlight for people the starvation that has arisen through this scientific data-driven, slave-to-all-that thinking. I think that’s what to me feels a very human, potentially very female sort of caring. An emotional, intuitive relationship with the environment, as opposed to that very separate, very distanced, very hands-off attitude.

Work in progress: “Flat Rocks 1”

Mathilde: To your point about the words that accompany the works, this makes me think of Ursula Le Guin’s third language of poetry, and maybe the language of the visual arts, and that conversations in this language are never finished. They are always open and continuing. When it comes to our Convergence works, each work leads on to the next one and opens up a different type of conversation with the materials, with the land that the materials have come from, and with the themes that arise from engaging with this specific land. The conversations are always echoing back into each other, so the process is never over.

We also often talk about our works as conversation starters, because we don’t presume we’ll come to an answer at the end of Convergence: ‘Okay, we’ve healed our relationship with the earth. This is how we should all relate, and this is how Sara and I are going to make art from now on. There we go. Problem solved’. Absolutely not. It’s about deepening and continuing to explore what that changing relationship is and seeing if anybody else might resonate with our process in how they relate with land. The artworks act as a starting point for that questioning and for that exploration for others. And it might be that the artworks themselves don’t particularly resonate with people, but do they serve as a moment to pause and question: ‘What is your relationship with the land? Where do you feel most connected? How do you enter into that relationship? Sara and I do it this way, what about you?’

Iain: There’s an Irish poet called Paula Meehan, who’s writing I absolutely love. She runs poetry classes for all sorts of people, and every time she runs a class, somebody will say:’ didn’t Auden …hold that poetry makes nothing happen’? She turns it on its head and says:

‘But maybe we might read that “nothing” as a positive thing. If poetry makes nothing happen, maybe it stops something happening, stops time, takes our breath away. Though, strange that taking our breath away, being breathtaking is associated with achievement, accomplishment. Maybe it’s like the negative space in a painting by which what is there is revealed, to be apprehended by human consciousness’.

So maybe that stopping something through art is really important. Maybe it makes a space, makes a space to allow questions to arise. It seems to me that one way of describing what you’re talking about is that it’s like a ritual opening of a space in which that can happen, a kind of a grounding that allows that space to open and again. Paula Meehan also quotes Gary Snyder’s What You Should Know to Be a Poet as saying you need at least one traditional form of magical practice, like the Tarot, as a way of doing ‘nothing’ precisely. So you sit down and you take a pack of cards and you make a layout, and the layout prompts questions. It uses imaginatively designed images to prompt questions. And you shuffle between the images, and you think, what on earth is this all about? And in a sense, that seems to me, parallel to what we do in the studio, and maybe even parallel to what we do in a scientific lab, if we see it in a particular way. Apparently about two thirds of the scientists in the United States are looking to get out and find jobs in Europe. Why? Because they can see what’s coming. For example, Donald Trump, is closing down all the medical work to do with women, because what he wants is to have a white male authoritarian state. Any scientist worth their salt is going to see what’s coming.

Sara: There’s a lot there that’s really interesting, because you were talking about laying out tarot cards and moving things around, which mirrors the artistic process in the studio as well. It makes me think of Mathilde and I being very socially connected. There’s something wonderful about working with the earth pigments and inviting people into that, starting conversations through the process of making, not just through viewing, which is inherently, intrinsically joyful and playful. And I think that ‘play’ is interesting because of the similarities with creativity. It’s like a treasure hunt. It’s about reigniting that awe and wonder which we, because of our systems, constructs and social norms, get beaten the hell out of us. We’re not allowed to have awe and wonder anymore. We have to be very rational. And the minute we invite people to experience awe and wonder through the playful joy of working with the earth paints, I hear them say that it’s like being a child again and making a mud pie. That’s great, because that’s real connection, and that’s opening up the dimension of us which is constantly suppressed. And I think that’s a big part of why the conversations we’ve talked about are not just verbal, they’re emotional and terrible and all those things.

Iain: I find that interesting, with having Ursula Le Guin in the back of my mind at the moment, because she talks about how in America the imagination is seen as childish. Real men don’t read fiction, or if they do, they read fiction about cowboys or bank robbers, tough male stuff, but they don’t read imaginative fiction. It’s in a wonderful chapter called, Why are Americans afraid of Dragons? Basically, our emotional value systems are very powerfully impacted by our education, by gendered expectations, all those things. Playing with mud pies, yes – Le Guin reminds us there’s a child in everybody – and the problems start when that child is denied. So, great to play with mud pies, but also to keep the mud pies connected to all these other things. It’s that business of maintaining the warp and weft. It’s great that all these things can be brought together and kept in conversation in some way. What fascinates me is whether you feel you have an equivalent to Hanien’s thing about getting the people who take on the art as owners having a particular investment in what they’ve taken on, to become champions for it, in a sense champions for the conversation.

Sara: We’re in the process of writing a manifesto that we want to accompany the works, a real statement about our purpose and our hopes and dreams, if you like, for what these works might represent. And we’re at quite an emergent stage with exhibiting and sharing the works. They’ve only been shown in isolation in a couple of places. But I think we’re very keen that if they find their way into a permanent home that’s not with us, that they sit alongside their manifesto, and then we are coming back to the relationship between the words and the artworks again…

Work in progress: “Flat Rocks 2”

Mathilde: … and also as part of any exhibition, we would like to include opportunities for people to interact with the source materials themselves, in the form of a workshop. That process of interaction with earth pigment painting is part of helping to engender a greater connection with the works and opening that exploration of our relationships with the land.

Something else that Sara and I have been exploring is making tissue paper casts of some of the rocks and pebbles that we’ve collected on the beach, and then painting them over with earth pigments, and then removing them from their rock. What we end up with is this ghost of a rock, this rock that’s lighter than air. We’ve had a few people interacting with those in the studio and seen the wonder that that’s provoked so we’d like to include that into any workshop offering as well.

Iain: I love the idea of having a doppelganger for a rock. That’s terrific, and it fits beautifully with some of the old animist traditions where everything had more than one form of being. So that sense that conventional categories are more fluid than we assume, the idea that the rock can have a kind of skin that belongs to it and doesn’t belong to it, is lovely. Our granddaughter was telling me about giants in Bristol recently and I remembering that that the islands in the Severn Estuary are supposed to be there because giants having a throwing competition. Stuff like that is now dismissed as childish, isn’t it? But those stories were presumably originally driven by the same impulse that animates scientific curiosity. People wanted an explanation as to why there were great lump of rocks in the middle of the Bristol Channel. And honoring that spirit of curiosity seems to me to be part and parcel of this, having this rich conversation, as rich a conversation as one can around all these things.

Mathilde: Absolutely, and I’d like to link that to something that you said before about authoritative discourses in science. And not oversimplifying the scientific method by assuming it is exclusively authoritative or unimaginative, stuck in its rigour and processes. Because I think science is inherently curious and imaginative. And, in particular, geology – the science that I know best – is all about imagination. It’s more about imagining what’s in the gaps of the rock record than relying on the geological evidence that we do still have available to us. So it’s an inherently imaginative process.

And I guess my desire would be to highlight and celebrate that creativity, by bringing some of the creative methodology Sara and I have been developing back into these formal scientific settings, to explore it with people whose creativity maybe feels very squeezed and suppressed in their everyday work and practices. Can we offer a bit of breathing space to allow curiosity and the imagination to flow through, and be open to what happens in that process? And can that opening of a space provide a bridge to other perspectives?

Iain: On a different subject, one of the things that struck me about Hanien’s work was that she was also using the burnt plant matter and they’re plants that need fire to generate. And again, there’s that kind of almost alchemical sense of something that has to be destroyed to regenerate. And obviously you’re destroying rocks to generate new things. But I think I was picking up on that at another level. We’re scared of destruction because we live in a culture which likes to encourage us to think that we can live forever and consume more and more, whereas we know perfectly well that everything has to die, change, mutate. I don’t know where that thought is taking me. It’s just that seemed to be a possible parallel, that idea of destruction feeding into the creation of something new.

Mathilde: Yes, maybe the link there is that we destroy rocks. I felt that very strongly when I was working in the lab, how violent and destructive the cutting up and grinding down of rocks was. It’s remarkable how quickly we forget the violence of what we’re doing, what we’re destroying, when it’s for a “scientific goal”. How quickly we forget the extraction from the land in the manipulation of the materials. And how unaware we become of what we’re losing in the process of extracting “useful” data. That data and knowledge might be very valuable and useful, so I’m not saying it’s a bad thing, but a question to ask ourselves might be: what is being lost in that extraction? Can we have a heightened awareness of the destruction necessary for extraction, and more gratitude for what is enabling us to gain more knowledge? In the context of Sara and I producing artworks, we are also inherently impacting our environment and extracting from it. We can’t just live in total isolation and not affect the world around us. But maybe what we are attempting to do is be more sensitive to our destructive impact and how we might mitigate it, where possible, by being more connected and in relationship with the places we extract from, and the materials we use as a result of that extraction.

Iain: It reminds me of tribal cultures where they thank the animal that they kill to eat, and there are rituals that you go through to honor the animal. You and the animal both know that that death and eating are basic, but you respect that. And you know clearly that in extract millions of tons of rock or whatever it may be, there is no respect involved. So, yes, I think that’s absolutely right, that business of acknowledging the violence, admitting that as part of the bigger picture, that the language of violence is also part of the language of creativity.

Sara: I think that the first pair of works we just called ’Flat Rocks I and II’. And we were really interested at that point, in stepping into each other’s worlds. I was accompanying Mathilde up to the lab and looking through the microscopes and witnessing this whole process of creating the thin sections that Mathilde just described. And then welcoming Mathilde here to the studio to handle those earths, that process, in a really mindful and loving way to create the paints. We talked about the total physical difference – the scientific destruction and the harshness of that mechanical process that is gone through with the goggles on and with the distancing – all the safety protection gear and everything else that serves to create more and more distance from the original piece of rock that was first taken back to the lab. By contrast, what occurs in the studio here is a process of getting to know it more and handling it and touching it and caring for it and managing that process of extracting the pigments and sieving. It’s a very physical thing, and we were really conscious of that and, ultimately, we’re both making flat rocks, but the process that we’re going through in order to get there is such a different one. The one in the studio feels anything but destructive, it feels very, very loving and very tender.

Addendum – drafted 02/10/2025

This conversation was recorded on the 28th March 2025 and captures where the Convergence collaboration was at that time.

Shortly after this, Mathilde and Sara experienced a fire in Sara’s studio which was profoundly shocking and necessitated a pause to practically and emotionally process the aftermath. Although none of the Convergence works were directly affected, a break from the collaboration was needed to give space to each of us to recover from what had happened, and explore where we wanted to go next.

The fire had the potential to destroy our collaboration. Our equal commitment, care for ourselves and each other, and the value we place on our work together, means that we now plan to resume Convergence in a reshaped form.

At what point is the State of Israel finally utterly discredited in its use of claims of “anti-semitism” as an excuse for dismissing its critics?

Recent revelations by researchers reported by The Conversation are sickening, not only for their detail but for what they say about the US establishment’s ongoing and unqualified support for the illegal actions of the Sate of Israel. (And not just that of the US).

I have tried to resist the urge to respond on this blog to evidence of the rapidly worsening global situation, both political and environmental. But there are times when that comes to seem like a craven avoidance of a responsibility that any half-decent human being should accept.

An update (of sorts)

I have not been adding to this blog for quite a long while, despite having had plans for various pieces I wanted to write. Up here in the north is normally an ideal place to catch up on projected writing. But neither have I been making the visual work I had provisionally intended to do when we came north at the end of September, retreating from the seemingly endless sound of building work on the house opposite us in the street.

Partly this has been due to my not being entirely well, but if I’m honest I think it has had more to do with the disturbance caused by the books I’ve been reading: bell hooks on place and on the visual politics of art and, more significantly, Naomi Klein’s extraordinary analysis of the digital mirror world, Doppelganger. Terrifying as what she reveals is in so many respects, it’s also clearly the case that it’s better to have a more complete understanding of what is happening in the digital world than not.

It’s not clear to me at present whether it’s better simply to withdraw as far as possible from that world – I have in any case been banned from Facebook for some time, for reasons that are entirely unclear and, as far as I can tell, unfounded – or to continue with this blog. No doubt something will prompt me to go one way or the other.

Fiona Hingston at Andelli Art

Last month I put up a brief post about Fiona’s forthcoming exhibition, “Local Artist”.

Earlier today I took a trip south from Bristol to see what turned out to be Fiona’s really rather wonderful exhibition. Her range of work has expanded considerably and now encompasses pieces that have a sly and disquieting humour I’ve not associated with her work in the past. I knew that Fiona has for many years been inspiration by her connections with the agricultural land around her home village on the edge of the Mendips. however, the catalogue suggests she’s also been inspired by the village itself. The former makes perfect sense but I can’t help wondering if the later applies to what to me is new too her work, her “Hay Dolls”. Given the qualities of these extraordinary pieces, I can’t help wondering about her neighbours or about just what they might make of these pieces in the exhibition?

If anyone reading this can get to see Fiona’s work I would highly recommend you do so. Andelli Art is just outside Wells – Upper Breach, South Horrington Village, Wells BA5 3QG. A perfect setting for a highly unusual body of work. I only wish I could have visited the exhibition with Lois Williams, who of all the artists I know would most appreciate Fiona’s use of materials. Unfortunately Lois lives in North Wales, far too far to travel to see the exhibition.

What particularly struck me, perhaps because I’ve not seen that side of Fiona’s work before, were the various pieces she entitles “Hay Dolls”. These somehow manage – at least for me and for the most part – to be both almost endearingly straightforward and, at one and the same time, somehow decidedly uncanny. They have that wonderful sense of both the immediacy and the imaginative open-ended-ness of, say, Japanese Yōkai spirit figures (as my daughter pointed out at once on seeing the catalogue), or else those strange twilight characters out of old European folk tales. (The “Doll” pieces all sold very quickly which, from my point of view, is just as well because otherwise I’d have been tempted to buy one for my granddaughter. Although she’d have had to wait a few years to have it – both for her sake – too uncanny for a six-year-old – and mine).

The exhibition also includes a variety of other fairly ‘minimal’ sculptural works and includes a number of drawings, of which the two large “Furrow” pieces are particularly impressive. I was also very taken by the two “Quilt” pieces and the five works in the Tithe Series, all of which use recycled cloth, hay, and other abject materials to make objects of considerable quiet presence.

Every Step Of The Way

Thanks, Sally Rooney.

I’m impressed and delighted that the popular Irish author Sally Rooney has publicly declared that she will support and give funds to Palestine Action. This despite the UK Government’s declaring it a “terrorist organisation’ because it has taken direct action to bring pressure on that same Government to make more effort to stop the genocide in Gaza.

For hundreds of years Britain’s governing and propertied elites have chosen to advance their own interests rather than addressing injustices and worse, both at home and in the wider world. We have needed outspoken individuals to draw attention to the situation. Significantly, it has been minority groups like the Quakers, who were continually and often violently persecuted by those in power for rejecting the authority of the Church of England and a “natural” order based on social hierarchy, for being pacifists, and for believing in equality between men and women, to draw attention to the ethical bankruptcy of those elites.

It’s the same tradition of publicly expressing ethical concern that informs the Quaker Huw Lemmey’s recent piece in the London Review of Books, which he concluded by stating that: ‘Resisting the destruction of human life and the perpetuation of a genocide against the Palestinian people is not wrong. It is the law, and this government, that is wrong’ (‘Short Cuts’ London review of Books 24 July 2025 pp. 10-11).

At a time when public opinion in opposition to the Gaza genocide is growing in Israel, despite every attempt by the Israeli Government and mainstream media to hide the appalling death toll and the human suffering being inflicted, it is important that all those opposed to that genocide speak out. We owe a debt of thanks to Sally Rooney for doing so.

Fiona Hingston – “Local Artist”

I’m posting this about an exhibition a friend of mine, Fiona Hingston, is having in what was once The Mendip Hospital Sanatorium. She’s called it “Local Artist”, because that’s what she is, and also as a riposte to someone who said at ‘Make’ – the Hauser and Wirth gallery on Bruton High Street – in a rather derogatory tone, ‘oh, but she’s a local artist’. That information alone would have been enough to take me to the exhibition.

The current genocide of the Palestinian people by the IDF has clearly been sanctioned by the Government of the State of Israel.

We visited a family friend today and he drew my attention to a short piece in today’s The Guardian. It’s by Professor Nick Maynard, a consultant surgeon at Oxford University hospital, who has been travelling regularly to Gaza for 15 years. He is currently volunteering with the charity Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP) at Nasser hospital in Gaza.

If anyone still doubts that the Government of the State of Israel is, through the agency of the IDF, actively engaged in genocide; or that the IDF is carrying out a sadistic policy of deliberately wounding starving Palestinians who are desperately seeking food, they should read Professor Maynard’s article at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jul/22/gaza-israel-deliberate-starvation-ceasefire-aid.

I realise that, given legislation introduced by the present British Government, if I were to put the heading of this post on a placard and enter a public place, I could hypothetically face prosecution, either for anti-semitism or for implicitly supporting a banded terrorist organisation. It is literally appalling that protesting against the actions of a genocidal State, supported by one that has a sexual predator and convicted felon for President, is seen by a supposedly “Labour” Government as a crime. While I agreed that causing deliberate damage to military hardware is not a sensible, let alone productive, form of protest, the British Government’s response to it is craven, disproportionate, and borders on authoritarianism.

If you have been waiting for me to return to my usual art-related topics in this blog, my apologies. Health problems and the state of the world have kept me otherwise preoccupied. Normal service will, I hope and trust, be resumed in the not-too-distant future.

Counterpoints: Walking to change direction

A one-day conference focussing on a cross-disciplinary approach to walking practices, land use, and future-thinking.

Professor Kate Soper, Hamish Fulton, The Stone Club,

Jack Cornish, Dr. Hope Wolf, Professor Harriet Tarlo,

Justin Hopper, Dr. Iain Biggs.

Friday 24 October 2025, 09:30 – 17:30

£50 including buffet lunch

Book online at: westdean.ac.uk/events

Image above: no horizons, a one day 50 mile walk, southern england, early spring 1976 Hamish Fulton