[This is the slightly amended text of a presentation given for a postgraduate conference organised by doctoral students at Cardiff University – Breaking Boundaries – given on May 11th, 2021.]

I’ll start with an observation by Stephen Sterling, Emeritus Professor of Sustainable Learning at the University of Plymouth. He points out that our education system can’t address the Climate Emergency because it’s based on, and helps maintain, the mentality that created that Emergency. This morning I want to look at elements of this situation. As the anthropologist and archaeologist Barbara Bender indicates, the landscapes I study make no sense from a single disciplinary perspective. To explore them I need to draw on many different areas of knowledge. I also needed to walk, listen, read parish records, study old field maps, notice weather patterns, and pay attention to a whole lot of other stuff too odd or ordinary for most academics to consider. So Barbara Bender is right, but her observation also has another, more significant, implication.

If landscapes refuse to be disciplined, if they make a mockery of oppositions between time [History] and space [Geography], or between nature [Science] and culture [Social Anthropology], then this must apply even more acutely to the psychosocial and more-than-human ecologies of which landscapes are just one part. Which suggests that the Climate Emergency requires us to think carefully about the limits of the disciplinarity education system. Not because there’s a problem with disciplinary knowledge as such, but because of the social effects of an education system that creates separate, specialist groups that competefor intellectual prestige and economic advantage. My concern is with those negative social effects, and how we might minimize them.

Many of us are angry because the authorities don’t act on the Climate Emergency. But recent research says that what particularly angers young people is that they also dismiss, criminalise, pathologize and patronisetheir feelings and voices. This Mexican retablo – it’s text reads: The girl Rocenda talks with the forest animals. Cure her, Virgin – suggests that’s always happened. But the situation’s gets worse when members of the current Government try to classify Climate Extinction as a terrorist group and propose a ban on teachers talking about climate change in class.

Late last year a friend asked me whether I thought she should discuss Jem Bendell’s paper – Deep Adaptation: A Map For Navigating Climate Tragedy – with students on this course. A course she set up because she feels Irish art education leaves students eco-illiterate. She accepted Bendell’s analysis that we face (I quote): “the potential, probable, or inevitable collapse of industrial consumer societies due to the direct and indirect impacts of human-caused climate change and environmental degradation”. But, as a tutor to a virtual course, she also knew she couldn’t provide the pastoral support that discussing those possibilities might require. Arguably, we all share something of her dilemma. We can ignore Jem Bendell’s analysis, along with the 500 plus scholars and scientists globally who agree with it. That’s the approach of Jair Bolsonaro, Donald Trump, and those who Bruno Latour calls “out-of-this-world” fantasists. Or we can collectively discuss Bendell’s analysis. But that would require those who would need to initiate that conversation to show care and respect for others, something they all-too-often lack. Even the first step, to genuinely listen to the concerns of others seems too much for them. But, odd as it may seem, our education system actually encourages them not to listen.

It assumes that those with power and authority are entitled to speak, and that those without it should listen. As Gemma Corradi Fiumara points out, it’s a system that binds us into a particular hierarchy. One based on the assumption that those who speak authoritatively do so because they already possess all the necessary knowledge. And, for that reason, they have no obligation to listen to others. It’s a hierarchy that avoids genuine dialogue and, instead, tends to create competing monologues. It doesn’t help that educators have been given less and less time to listen by those who manage them. There’s a bitter irony in the fact that this erosion of time to listen in education has coincided with an ethical turn in the philosophy of science; a shift from focusing on “matters of fact”, to “matters of concern” and, more recently, to “matters of care”.

A second bitter irony is the contrast between society’s fetishization of consumption, marketed through notions of unlimited choice, and it’s education system’s limiting of choice by insisting on specialization.Specialisation that denies individuals a broad education and, as a result, limits their understanding by reducing their ability to connect and discriminate across many different types of ideas and practices. No wonder we find it so hard to understand psycho-social and socio-environmental processes and relationships. In short, our education system is structured by the same fractured, exclusionary mentality that has helped create the Climate Emergency. One way we can counter this is by cultivating mutual accompaniment and ensemble practices. But before I talk about them, I need to ground what I’ve just said in particular examples.

These people are climbing a protective dyke in the province of Groningen in the Netherlands. It protects the province from the sea, but is itself threatened by the increasing number of earthquakes there, caused by years of natural gas extraction. These people had come from three continents to share their experience at a workshop called Resilience, Just Do It, organised by six doctoral students who’d been listening very carefully to people in the region. I was there to talk about artists working with local communities but, because of our different experiences and practices, I started by talking about language.

I showed this photograph to illustrate how the meaning of words shifts. A photograph of the Bullingdon Clubevokes perhaps the most resilient element in British society – that is, a wealthy elite that does all it can to resist any change that might threaten it’s power. If I use resilience in the context of human society, it quite properly suggests resistance to fundamental political change; a resistance that may not coincide with the wellbeing of our civil society as a whole. But this meaning can be disguised because ‘resilience’ as a term in the ecological sciences is value neutral. It simply refers to an single eco-system’s ability to fend off ormanage threats that might otherwise undermine it. Our society is not, of course, a single eco-system.

Groningen university is unusual in acting rather more like an eco-system. All its Faculties must contribute to one or more areas of collective concern – Healthy Ageing, Energy, and Sustainable Society. This limits the power and autonomy of those academics whose approach to disciplinarity is in terms of territories that allow them to gain personal power and influence, rather than to contribute knowledge to the collective understanding. It also encourages staff to remember that their research must take account of those people who will bear the consequences of the researchers’ decisions. All this contrasts with a criticism of UK universities made by a former Principal and Vice-chancellor of Aberdeen University. He argues that the UK’s universities are perhaps the most conservative of its major institutions. A situation created and maintained by a realpolitik – that is, the way power and influence actually operates in and through persons and institutions – that’s deeply embedded in the hierarchies that mange the production of disciplinary knowledge. In his view, this makes British universities increasingly unfit for purpose.

I’m going to give you an example of the relationship between disciplinary realpolitik and political control. While I’m doing that, please keep in mind the UK Government’s recent dismissal – as “barely believable” and “a political stunt” – of the UN’s report on poverty in Britain. A report that finds that (I quote): “much of the glue that has held British society together since the Second World War has been deliberately removed and replaced with a harsh and uncaring ethos”.

Some years ago, a research team from a major UK university received over five million pounds for a project. This included, for the first time ever, money provided directly by the Department of Work and Pensions. In time the researchers submitted their findings to a leading medical journal. These were peer reviewed, accepted, and published. The most senior British academic in the researchers’ field described the research as “a thing of beauty”. The DWP prepared to use them to help justify cuts to disability spending. Insurance companies prepared to use them to justify paying out less money to claimants with certain disabilities. Then a problem occurred. The research findings directly contradicted the experience of many of the patients suffering the illness the study claimed to research. They alerted other researchers, who asked for access to the team’s data and methodology – access that’s a condition of publication in that journal. The researchers and journal refused. The case eventually went to court and, despite the university spending over two hundred and forty-five thousand pounds, its researchers were ordered to release their data and methodology. External scrutiny then showed conclusively that their findings had been fundamentally distorted by a methodological slight-of-hand. As a result, some universities now use the project to show how not to do such research.

So why didn’t the peer reviewers spot the problem and why, when asked, wouldn’t the editor and researchers share the data and methodology? Why did a very senior academic publicly praise such flawed work? Why has the journal still not retracted this discredited article? And why did a university go to court, at very considerable expense, to try to hide scientific research from legitimate external scrutiny? Perhaps because of undeclared conflicts of interest, since it later came to light that members of the research team had close links with both the DWP and the insurance companies. Another answer would be: “that’s disciplinary realpolitik for you”.

Many academics would describe the workshop illustrated here as interdisciplinarity. I see it as an example of mutual accompaniment. What’s the difference? Interdisciplinary thinking still tacitly privileges disciplinarity as the way of structuring knowledge. But at Groningen the organisers made sure that disciplinary knowledge was not privileged over that of farmers, parents, the elderly, community workers, children, local political representatives, or the voluntary maintenance team at the local auxiliary pumping station. They took a non-hierarchical approach to different types of knowledge and understanding. One that’s central to exploring, through genuine and respectful dialogue, the possibilities for practical, situated, and mutually enacted socio-environmental care. I stress this because we need to question the assumption that disciplinary knowledge – including its ‘inter-‘, ‘trans-‘, and other variations – is the only authoritative basis for understanding and action. If we don’t question that we risk contributing to the devaluing, trivialising, dismissing, or excluding of other forms of knowing and understanding. And that, in turn, leads to the dismissal, criminalising, pathologizing and patronising of the feelings and thoughts that animate dissident voices, including those of people who want action on the Climate Emergency.

In case there’s any doubt in your minds, I’ll repeat what I said earlier. I am not questioning the value of disciplinary thinking. What I’m questioning is the mentality that isolates specialist knowledge so as to create exclusive institutional domains; groups more concerned to concentrate their own power than to serve collective needs – a mentality that has very real social consequences. In a recent report, a senior neuroscientist makes it clear that it’s that mentality that has set Alzheimer’s research back by 10 to 15 years; while another says that millions of people may have died needlessly as a result.

Mary Watkins begins her book Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons with a quote from an Aboriginal Activist Group that explicitly challenges the exclusionary, hierarchical and patronising assumptions built into the disciplinary system. It goes: “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together”.It’s a request for mutual respect across boundaries that’s central to decolonising knowledge. It’s necessary because of the long-standing entanglement of the effects of colonialization, environmental abuse, social othering, and the disciplinary education system. I’d need a very much more complex diagram than this to visualise that legacy which is, in any case, far too complex a topic to deal with here. Instead I’m going to flip that entanglement over. I want to share, instead, an example of mutual accompaniment that shows how the legacy of that entanglement can be acknowledged and some of its effects healed, if only at an individual level.

Back in March a young South African artist emailed me, part of an ongoing exchange we’d been having about a possible PhD project. I’ll share part of it with you in an edited form.

“Recently I gave a talk to some local Motswana artists. I also discussed my struggle to belong in Africa with them. And they shared their struggles to find their traditions in the shards left after colonialism. Not that Botswana was ever colonized, but their indigenous culture suffered tremendous loss because of European influence. The artist-in-residence here is looking to de-colonize and re-claim, as a Tswana, the practice that European anthropologists categorised as ‘rain making’. That’s a miss-translation – ‘rain asking‘ would be more accurate. Our shared interests mean we’ve continued our conversation on-line, along with a few other Motswana writers and artists. It’s been very enlightening. Being accepted by this group has been very moving for me as an Afrikaner – an undesirable because associated with apartheid. This is the start of a very interesting, unofficial, PhD for me!”

That email suggests why mutual accompaniment in the process of decolonialising thinking helps confront a situation that sociologists of knowledge describe as follows:

“To the extent that a particular way of producing knowledge is dominant, all other claims will be judged with reference to it. In the extreme case, nothing recognisable as knowledge can be produced outside of the socially dominant form”.

That socially dominant form of producing knowledge currently allows the appropriation and ghettoization of knowledge – for example about Alzheimer’s disease – by disciplinary power groups that claim to speak authoritatively but don’t listen. As Amitav Ghosh so clearly demonstrates in his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, our education system makes it extraordinarily difficult for us to grasp the extent and impact of climate change. It teaches us to assume that only the socially dominant form of knowledge production delivers the “right” views and answers. So our education suggests that alternative views and answers are, almost literally, unthinkable.

Our education system rarely refers to the limits and bias built into our categorically-based knowledge system. But, as the feminist philosopher Geraldine Finn wrote back in 1990:

“…the contingent and changing concrete world always exceeds the ideal categories of thought within which we attempt to express and contain it. And the same is true of people. We are always both more and less than the categories that name and divide us”.

The system’s emphasis on fixed categories and division-through-naming has reinforced a mentality with terrible consequences. It’s naturalised the process of “categorical othering”. The year before Finn’s paper, the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman published a book called Modernity and the Holocaust. In it he argues that the lethal “othering” of Holocaust victims as less than human was not a unique expression of Nazi ideology, but an extreme expression of a foundational presupposition within modernity itself. In particular, of the negative social consequences of modernity’s over-emphasis on an attitude of mind – on the ethically neutral or “objective” detachment which has also made modern techno-industrial progress possible. The ethical neutrality and detachment that erodes what Hannah Arendt calls: “the animal pity by which all normal men are affected in the presence of physical suffering”, and that has fatally distanced the modern world from its relationship to, and dependency on, all other-than-human life.

I now want to bring all this closer to your immediate context as post-graduate students. Here’s an account sent me by a recently graduated doctoral student. I’ll call her X. In early 2019, X took part in a major international conference where she showed one of her films and talked about how she activates communities towards climate change engagement. She was subsequently invited to submit a paper to a special issue of an environmental science journal. However, following peer review and three rounds of major amendments, her paper was rejected. X knew this is not uncommon and actually got a lot out of the process. What frustrates her is that the peer reviewers and editor acknowledged that her approach to community activation is exactly what their field needs. They also admitted that it can only be done by arts practitioners like herself. Despite moving her manuscript much nearer to the structured format they required, it was still rejected as insufficiently scientific. When X explained to the editor that this was because she’s an artist, she received a very illuminating reply.

Firstly, the editor expressed sincere disappointment at not being able to include X’s work in the journal, conceding that sustainability scientists like to think they work with artists, but instead convert their work into something more acceptably scientific. X was then congratulated for sticking to her position as an artist, and thanked for prompting the editor to consider how the refereeing process undermines what artists can contribute to environmental science’s approach to the climate debate.

X felt the editor could have shifted just a little, but choose not to – despite recognising the seriousness of the Climate Emergency and X’s contribution to addressing it. I share her frustration but, as a former journal editor, I’m also know something of the pressures editors work under. So I’ll simply remind you that Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy was also rejected by a major environmental journal as ‘insufficiently scientific’. The question in both cases is simple enough. What is more important, maintaining the boundaries of disciplinary exclusivity or addressing the Climate Emergency? Unfortunately, the academic answer seems to be the first.

Increasingly, people are finding alternative forms of knowledge, understanding and ways to act that bypassthe socially dominant forms. Some do so through adopting ensemble practices and mutual accompaniment. That’s to say, they’re finding more inclusive, less hierarchical, ways of connecting to their own identity, to each other, and to the contingent and changing concrete world. The immunologist and poet Miroslav Holub points out that specialist disciplinary work is actually located in small, largely confined – if at times pervasive – domains in relation to society as a whole. So that, despite having been educated to identify with a specialism, most of us are engaged in all sorts of other roles and activities. He writes:

“… for myself, I would say that I spend 95% of my time and energy in fighting my way through the wild vegetation of circumstances, looking for the tiny spots, for the little clearing where I eventually could really work, write or do research … Why, then, should it make so much difference, being the poet and being the scientist, when 95% of our time we are really secretaries, telephonists, passers-by, carpenters, plumbers, privileged and underprivileged citizens, waiting patients, applicants, household maids, clerks, commuters, offenders, listeners, drivers, runners, patients, losers, subjects and shadows”.

Given this situation, we could choose to accept our multiple identities for what they are – a fluid and changing ensemble of different roles and practices. Not to do so, Holub implies, is to risk indulging in unrealistic, exclusive, even cultish, attitudes. Our lives are now dominated by vast meta-systems of management and manipulation, by an increasingly autonomous merging of corporate and political power. But at least part of their power over us depends on us passively accepting fixed identities.

One way to challenge this situation is to recognise the link between Holub’s description of our multiple life roles and Bruno Latour’s discussion of the importance of moving beyond binary positions for the emergent Terrestrial politics. He writes that:

‘…what counts is not knowing whether you are for or against globalisation, for or against the local; all that counts is understanding whether you are managing to register, to maintain, to cherish, a maximum number of alternative ways of belonging to the world’.

This inclusive approach – both to identity and our encounters in the world – is my cue to introduce you to some ensemble practices. That’s to say to the practices of people productively entangled in both mutual accompaniment and a maximum number of alternative ways of belonging to the world.

Ffion Jones earns a living as a hill farmer and a lecturer in Theatre and Theatre Practices at Aberystwyth University. She both embodies and questions the roles of daughter, mother, and partner in a Welsh-speaking hill farming community. Miroslav Holub saw himself as fighting his way through “the wild vegetation of circumstances” to get to the small space where he could work as a poet and scientist. Ffion, by contrast, has embraced that “wild vegetation of circumstances” as intrinsic to her ensemble practice. One that meets her economic and domestic needs and her desire to actively engage with, and articulate, the pressures on, and changes in, her community. Pressures she spoke about in a recent podcast on issues around re-wilding and re-forestation, as seen from the perspective of a Welsh hill farming community.

Ffion’s practice-based doctoral research combined performance and rural studies to explore the particular way of life of Welsh hill farmers, specifically their relationship with their livestock. In academic terms, it involved ethnographic fieldwork conducted through conversations with members of her immediate family and the local farming community, mediated through film-making and performance. But to categorise it as an inter-disciplinary project would be to seriously misrepresent it. It’s an ongoing act of mutual accompaniment, a life lived alongsidea particular hill-farming community from within. A giving voice to all the richness and contradictions of acontingent and changing concrete rural world. A lived process that perhaps only an ensemble practice can make possible.

Liz Hingley, who took these photographs, trained as both a documentary photographer and a visual anthropology. The largest image here is of a shelter on Hampstead Heath, built by a front-line nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic straight after finishing a fourteen-hour night shift. if you look carefully you can see her hands. Because the nurse finds her vision and spatial orientation limited for a period after the long hours of strong lighting and engagement with machines, Liz chose to photograph her in black and white.

Previously, Liz has explored the systems of belonging and belief that help shape cities around the world, working collaboratively to create connections between disciplines, cultures, audiences, eyes and minds. After projects in Birmingham, Shanghai, London and Austin, Texas, she developed a keen interest in the relationship between art and science, and became an Honorary Research Fellow at the departments of Philosophy and Physics at The University of Birmingham. More recently, she’s modified that interest so as to link her growing environmental concerns with the therapeutic function of woodlands during the pandemic. She’s currently developing a therapeutically-based photographic project with the staff of a London hospital, working alongside an ecologist responsible for Hampstead Heath; a project she hopes to fund through a bursary for a PHD in medical anthropology.

Ffion and Liz, and the others whose work I’ll briefly refer to, might be loosely identified as artists. A label they accept for pragmatic reasons and, incidentally, the reason I know them. But their work exceeds, and would for many art critics fall short of, the ideal category ART. Their concerns have mutated and, what were once simply matters of intellectual or aesthetic enquiry, are now equally heartfelt concerns requiring commitment and collective caring. Some years ago, Simon Read observed that our eco-social problems require (I quote): “a particular kind of strategy that our culture has yet to develop and promote”. What I’m suggesting this morning is that ensemble practices oriented by mutual accompaniment may provide just such a strategy.

Cathy Fitzgerald trained and worked as a micro-biologist in her native New Zealand before moving to Ireland. There she studied art, worked on sci-art projects, and for environmental organizations and the Irish Ecology Party. Inspired by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, she started looking for ways to interweave her artistic, scientific, political, and locally situated knowledge and concerns. In 2008 she and her partner moved into a small commercial Sitka Spruce plantation. She began to transform it into a sustainable, mixed species native woodland, something she estimates will take at least forty years. Working with international experts and using innovative methods, she set up exchanges between foresters, policy-makers, artists, environmental writers, philosophers, politicians, cultural geographers, and her local community in County Carlow. Those exchanges were then shared through regular blog posts and part-time teaching. In 2019, needing a steady income, she applied for, and won, funding to develop the on-line Haumea Eco-literacy courses she now co-teaches.

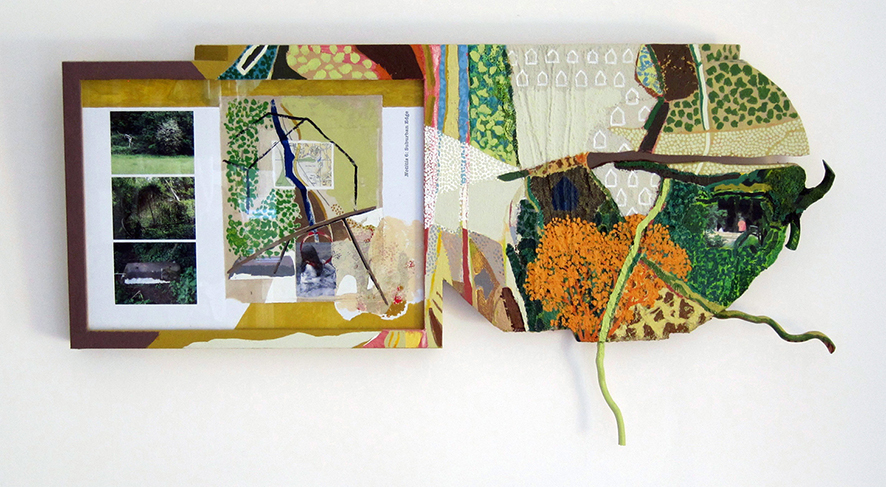

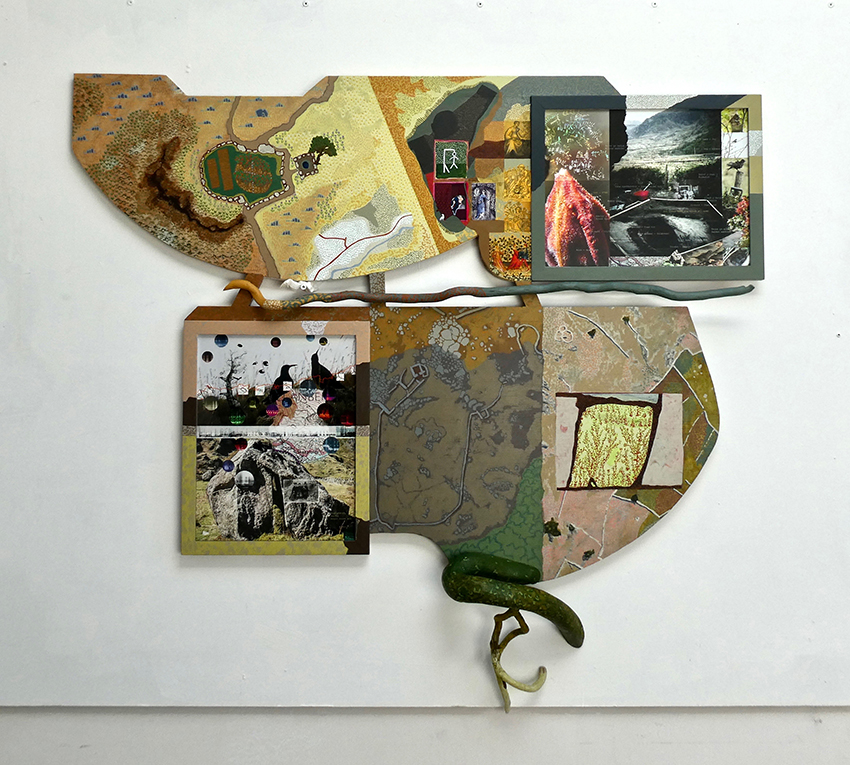

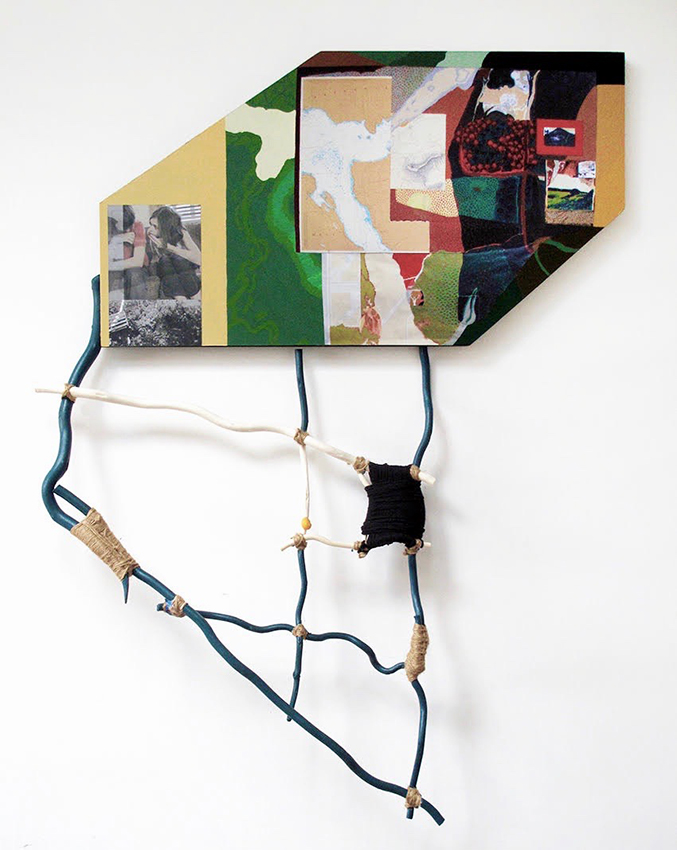

For fourteen years Luci Gorell Barnes was artist-in-residence at Speedwell Nursery School and Children’s Centre in Bristol, and still earns a living as an educator and researcher. Simultaneously, she’s been occupied as a collaborator with her musician partner, as a mother and, more recently, grandmother, and as a writer, illustrator and studio artist. She views all these activities as mutually intra-dependent. Her underlying concern is to develop (I quote) “flexible and responsive processes that enable us to think imaginatively with ourselves and each other”. This concern is particularly clear in her work with socially vulnerable individuals – disadvantaged children and refugee and migrant mothers. She helps transform their sometimes grudging institutional acceptance by a combination of place-making and situated learning, both grounded in forms of mutual accompaniment that embrace her whole immediate neighbourhood. Recently Luci worked on a nation-wide Hydrocitizenship initiative, drawing on her long involvement with water and food security issues.

Originally a successful London-based studio artist, Simon Read moved with his partner to rural Suffolk, where they and their son lived on a boat. There Simon equipped himself to join environmental planning debates around river and coastal salt marsh management by using his drawing skills to make maps that synthesize data so as to visualize likely future environmental change. This led to him working on a tidal attenuation barrier for the River Debden Association, co-designing it with local engineers and building it with the help of volunteers from a local prison. Simon, who is also an Associate Professor of Fine Art at Middlesex University, has initiated several other projects concerned with coastal salt marsh stabilization, using “soft engineering” that degrades over time. As a result of his environmental experience, he repeatedly stresses the need to reframe the relationship between land, ownership, responsibility, and belonging.

I’d originally planned to take my examples from the UK and Ireland, but realised that misrepresented the ways mutual accompaniment can link people across continents. Mona E. Smith is the founder of Allies media/art. She’s a Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota, grew up in Redwing, Minnesota, and became a college teacher. After re-discovering her Dakota heritage, she started researching and making documentary videos about problems facing native people in Minneapolis St Paul. She became a media producer and made work on health and other topics related to Dakota lives. She studied with Dakota elders, brought up her children, kept an eye on her elderly mother, and worked on a variety of arts and media projects. We shared work through a network focused on issues around place, and she then adapted a form of deep mapping to create the Bdote Memory Map. It’s a virtual, explorative web site for Dakota people to study their history, language, and traditional knowledge. It also includes guided walks to their sacred sites in and around Minneapolis St. Paul. But it’s also an act of recuperation that invites mutual accompaniment, using Dakota knowledge and experience to invite a change of heart in the descendants of those colonists who first appropriated, and then violated, the land and rivers that the Dakota people had always regarded as their sacred relatives.

Lindsey Colbourne lives in North Wales but has travelled and worked internationally. She has twenty five years’ experience as a professional facilitator, trainer, advisor, and designer of participatory processes –particularly conflict resolution and dialogue. She’s also worked for the UK Sustainable Development Commission and as a surveyor for the British Trust for Ornithology. All of which now informs an ensemble practice with art as its catalyst. She uses collaborative and participative inquiry to forge new connections and to work with and through different ways of knowing the world. Her aim in these investigations is to involve as many different people – and perspectives – as possible, an approach that echoes Bruno Latour’s statement quoted earlier. She tries to begin each project from a point of ‘un-knowing’, avoiding disciplinary presuppositions and without anticipating the outcome. She then uses whatever approach – from conversation to photography, gardening, or performance – that seems appropriate and simply “follows her nose”. She writes (I quote): “sometimes the work stays in the process, living in the dialogue and the relationships it creates, with no formal art ‘outcome’ at all”. Hers is a genuinely open-ended approach, a letting go of conditioned expectations, that informs the mutual accompaniment I’m proposing here as onealternative to the disciplinary mentality.

I’ll end, however, by bring this back inside the academy, since that’s were you find yourselves.

Lindsey’s concern – to live in the dialogue and the relationships it creates – links directly with an account of the real value of Arts and Humanities research from two anthropologists, James Leach and Lee Watson. They show that the institutional criteria used to evaluate Arts and Humanities research bear no relation to how innovation and creativity actually occur. Instead, the real value of such research lies in its being carried by and in persons – as expertise, as confidence, as understanding and orientation to issues, problems, concerns and opportunities, as tools and abilities. All qualities they suggest are best seen as responsivenessor, if you like, as the animation of acts of mutual accompaniment. Leach and Watson also point out that these qualities are probably best understood as aspects of citizenship; as emphasising spaces and opportunities for discussion, argument, critique, and reflection. The spaces in which active collaboration becomes a basis for evaluation.

In short, they suggest that Arts and Humanities research needs to be seen as having value as a dialogic process in its own right. That it should be understood, first and foremost, not as an instrumental system for producing disciplinarily-defined “research outcomes”, but as an important, perhaps central, contribution to a proper discussion of what a sustainable education should be.