twentytwelve domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /home/etm3eoykc3kx/domains/iainbiggs.co.uk/html/wpress/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6131

I heard today from an Irish friend that Tim Robinson, the artist turned writer and cartographer who was best known for his two volume Stones of Aran and his books and maps of Connemara, has died as a result of CORVID-19. He passed away at St. Pancras hospital on 3 April 2020 at the age of 85, two weeks after the death of his wife and collaborator Mairéad Robinson.

Sadly, I never did manage to meet Tim Robinson, whose work I greatly admired, although I had expectations of doing so on one of my visits to NUI, Galway. He became ill and moved back to London before that became possible. His work has always seemed to me an inspired example of a particular tendency within the broader ‘deep mapping’ mentality, sharing with Cliff McLucas and others a profound understanding of the importance of the relationship between language and place. I heard much of him and Mairéad through my friend Nessa Cronan at NUI, Galway, which houses his archive.

Although, with many others, I mourn his passing, I also know that we are very fortunate that he had the foresight and generosity to give the university his very extensive archive. This is, in itself, a celebration of so much and I remember being deeply moved by the event organised by Nessa that marked its opening, something of which is also evoked by Deirdre O’Mahony’s film here.

In 2008 I spent some time wondering how to reconcile the need to work as simply as possible with the desire to articulate the richness and complexity of a place. In particular the land around St. John’s Chapel in Co. Durham, which, with my family, I have been visiting each year for over 40 years.

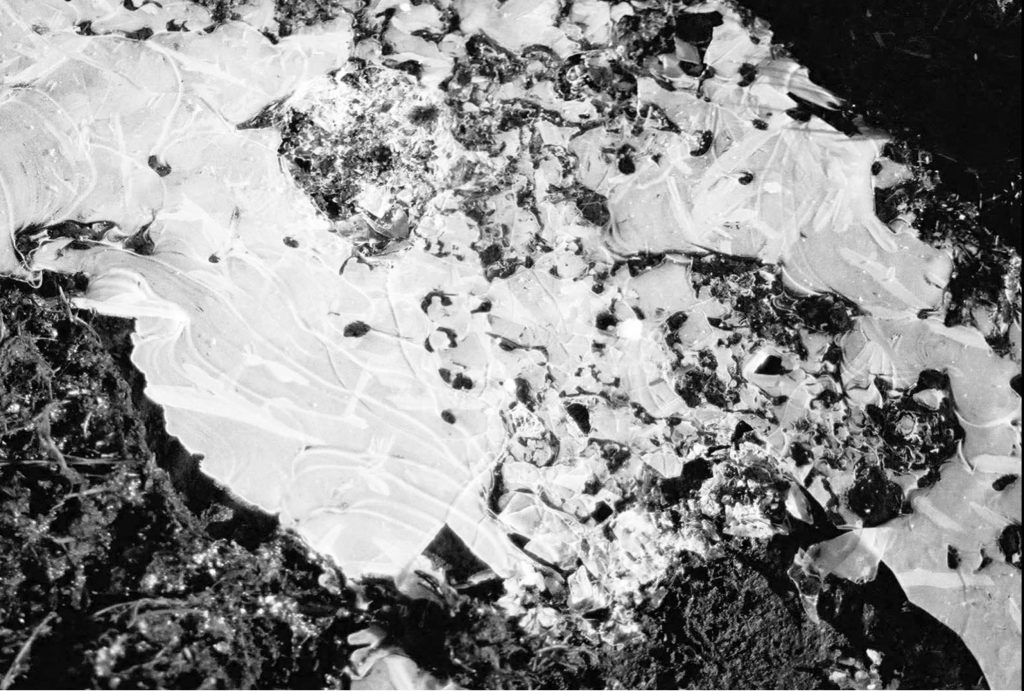

The approach I adopted then was to make an inter-weaving of images taken on six walks, using black and white to stress the qualities of light and texture so specific to that place. The original images were accompanied by short pieces of text that focused on the sounds encountered walking there.

Given the current restrictions on walking, it seems appropriate to revisit this project and, at least in part, to rework it. I have stayed with the idea of presenting these revised inter-weavings in six sets of eight, echoing the rhythms of the original piece. The six sets no longer evoke specific walks, although their ‘trace’ runs through the piece as a whole. Instead I have ‘thickened out’ my description by breaking into the original walks and substituting supplementary material, all of which comes from the same area of land.

I will post the full set of six sections over the next few weeks. I’m now unsure about the text I used in the original. If I add it it will be as another supplement, at the last post in the series.

In a recent blog post called Online Tentacular Lindsey Colbourne writes about various new ‘tentacles’; including two she’s trying to develop ‘at a distance’ in terms of online collaborations based on place, one of which is with me. This involves our doing something around the idea and symbolism ‘Corlan’ (fanks, folds, stells, or enclosures depending). I put up a post about the start of this exchange – In Troubled Times – back in April and, given Lindsey’s post, it seems a good idea to pick up on where this has gone since, particularly as the tensions around the idea of enclosure (those place that protect by limiting freedom to move) has become increasingly relevant since then.

Our on-line exchange on this, following my all-too-brief visit to Dyffryn Peris, began with Lindsey explaining to me that the Welsh term for what I would call a fank is Corlan, basically COR; ‘small’ and LLAN ‘enclosed open spot/patch’. This is also used for larger enclosures like areas of land or villages.

Taking this as a starting-point, I began to assemble a whole plethora of material, during which some underlying questions began to form. One of these relates to Tim Ingold’s reminder us that, when we are in a taskscape listening, we are at the centre of the sound-world; whereas when we are looking we are always at the edge of a ‘field of vision’ looking ‘in’ or ‘out’. (Of course these two activities are almost never wholly separable, but the point remains valid if thought in terms of emphasis). This prompted the beginning of a question along the lines of: “is any link between an emphasis on either listening or looking and the shape of a dwelling”?

The circular (associated with a privileging of listening) in relation to buildings would relate to Gaston Bachelard’s discussion of the phenomenology of roundness – “For when it is experienced from the inside, devoid of all external features, being cannot be otherwise than round”. (The Poetics of Space p. 234). The square/rectangular, by contrast, would seem to presuppose a worldview in which sight oriented outwards (including, perhaps, the notion of the four cardinal points is stressed. This gives a more differentiated sense of world, one in which we look out in different directions that, in turn, are given differentiated qualities.

I then looked at a great deal of archaeological material, which suggests that both circular and rectangular enclosures – whether built for human habitation or the protection of domestic animals, have existed for the last 6,000 years. Both can be related to the Welsh term Hafod – a summer place (equivalent in terms of place to the English/Scottish Borders term sheiling) – and in both cases a relic of the ancient practice of seasonal transhumance.

But if these point to a type of place in the semi-nomadic agricultural world of seasonal transhumance, Corlan can also be related to other enclosed spaces – for example the portable herb garden that supposedly belonged to Siwan, the Lady of Wales, who lived at Dolbadarn castle just down the valley on Padarn Lake. (There is an argument that the architectural design of different parts of the castle can be seen as ‘male’ and ‘female’, with the garden area being central to the ‘female’ part. This in turn relates to the hortus conclusus or enclosed garden (and so by implication to the medieval symbolism of the Garden of Paradise). These nested senses of enclosure as symbol, taken together, played an important part in shaping medieval attitudes toward both women and nature. The sexual ambiguity involved is heightened at Dolbadarn because, in 1230, the English knight de Braose and Siwan began an liaison. He was later charged with adultery and hanged, after they were caught in the chamber she shared with her husband.

Ironically, Dolbadarn would later be used as a ‘vaccary’, that is a corlan for cows.

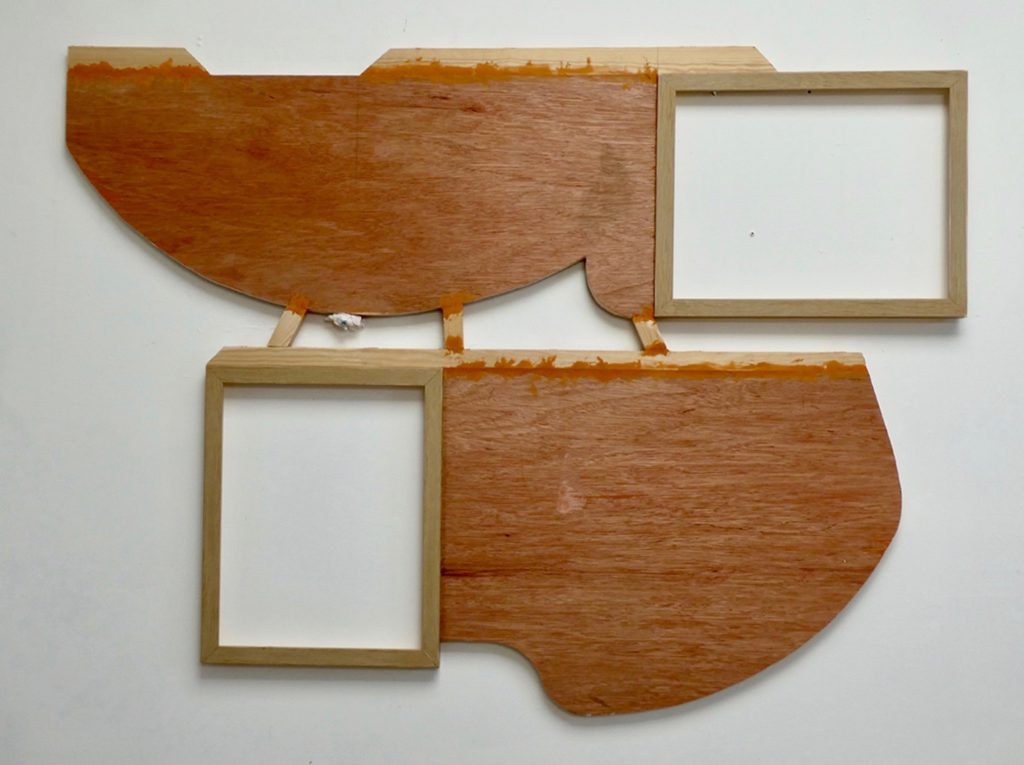

All of which is fine but, for me, to be any real use it had to lead to a physical form I could work with. Fortunately, while I was ruminating on what on earth to do with all this material, I came across Alice Aycock’s construction: History of A Beautiful May Rose Garden in the Month of January (1978) and looked at the material she drew on. Most importantly, Sano di Pietro’s Annunciation to the Shepards with its corlan and castle. As a result, I’ve now arrived at a constructed support that allows me to start to focus the material touched on above and to begin a more concrete collaborative conversation with Lindsey.

More on this project in due course.

On Thursday of this week we in the UK will vote in what will be the most important election of our lives.

An election that will determine how this country responds to the climate change crisis. We now know that, unless this rapidly deepening crisis is addressed speedily and radically, it will entirely destroy the world as we know it. (Indeed, Professor Jem Bendell and other professionals in sustainability management, policy and research suggest that it may already be too late to address the causes of all-but-inevitable near term social collapse).

How UK citizens vote is, of course, entirely their choice. The purpose of this post is not to ask you to vote for a particular party (however much I might want to do that). Rather this is a request, from somebody who has spent a lifetime working with young people in Further and Higher Education, that you consider very carefully indeed what is really at stake in this election.

Important as issues such as Brexit and the National Health are today, they may all too rapidly pale into insignificance besides the environmental, social and psychological impact of the deepening crisis generated by climate change. A crisis that will inevitably have the greatest impact on those currently too young to vote.

If you have not already done so, please consider this situation very carefully before you cast your vote. It could make the difference between electing a UK government that pays lip-service to addressing this crisis while really focusing on conducting ‘business-as-usual’ and one that will actually make some real attempt to avert the crisis, or at least work towards mitigating its worst consequences.

Thank you.

In memory: Hugo Ball, 1886-1927

[The following is a slightly modified version of the text of a presentation given at the ‘Walking’s New Movements Conference’ in Plymouth – November 1st to 3rd, 2019. This was organised by Helen Billinghurst (University of Plymouth), Claire Hind (York St John University) and Phil Smith (University of Plymouth), to whom sincere thanks are due for putting together such a convivial and informative event].

In 1917, Hugo Ball broke with Tristan Tzara and Francis Picabia over their ambition to turn Dada into an international art movement. Ball then ‘walked away’ – both from Zurich Dada and, as it turned out, from making art. Today, artists like Jeff Koons have infantilised Tzara and Picabia’s radical nihilism, pandering simultaneously to both the most toxic and the most trivial aspects of possessive individualism.

My dedicating this presentation to Hugo Ball stems from his rejection of possessive individualism, a rejection based on his belief in the ultimate unity of all beings and the totality of all things. But equally from recognition of his acceptance of the need to accept the dissonances that follow from that conviction. Hans Richter reports that Ball ended his life: ‘among poor peasants, poorer than they, giving them help whenever he could’ and that, fourteen years after his death, they still spoke of him with love and admiration.

My involvement in what I’ll refer to as ‘open deep mapping’ – to distinguish it from forms of deep mapping used to serve disciplinary ends – relates to Ball’s concerns in two ways. Firstly, because it offered me ways to work towards that sense of unity and totality, working with the dissonances and contradictions inherent in a particular place or region to do so. Secondly, because it required a walking away from art made in the image of possessive individualism in order – to quote Les Roberts on deep mapping as bricolage – to find: “a ‘space in-between’ in which to squat in a provocatively ‘undisciplined’ manner, shrugging off the settled weight of an institutional or disciplinary habitus”. (Personally, I’d modify that slightly and say: “a space-between in which to pace in a provocatively ‘undisciplined’ manner”).

On the 15th of April, 1999, exactly a month after Loyalist paramilitaries murdered the solicitor Rosemary Nelson, I went walking in the streets of Belfast. Some of the city’s sectarian borders were still visible through curb stones painted red, white and blue, others were not, but the background of fear and anger were palpable. Four months after my walking in that city of literal, conceptual and psychic borders, I began a fourteen-year-long open deep mapping project that follows the meanders of one of the many tributaries that helped feed that fear and anger. A project oriented, first and foremost, by an unlikely resistance to a culture predicated on violence – a resistance enacted tacitly, through the preservation and performance of a handful of very old ballads, sometime referred to as ‘supernatural’ but, in fact, focused on the cunning and endurance of women.

These photographs were taken when walking at Scot’s Dyke, which marks the English Scottish border just north-east of Carlisle, where it crosses the Debatable Land. This is the region that, historically, was the most ravaged by the consequences of wars between the English and Scottish crowns. These locked it into a cycle of violence from the late thirteenth into the early seventeen century. Walking here today, you only hear the wind, distant cattle or a tractor or, if you’re lucky, a buzzard’s cry. What’s obviously inaudible is the act of breaking of that cycle of violence – the State’s use of mass hangings, forced enrolment of large sections of the male population into mercenary regiments fighting in Europe, and the exile of entire extended families to County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland.

I’ve started here in the Debatable Land because this place gave a name to the Debatable Lands open deep mapping project I worked on for so long. By excavating and following traces of narrative that led me here, I came to touch an engrained anger and fear – but also alternatives to them – that were exported first to Ireland and, later, to the USA. Traces that draw attention to just one small thread in the UK’s contributions to what Amitav Ghosh calls ‘The Great Derangement’.

Open deep mapping – which may be what Les Roberts calls ‘deep mapping as bricolage’- is fundamentally peripatetic. It’s grounded by a walking body getting to know a place through all its senses. It’s also intellectually peripatetic, wandering freely across disciplinary and conceptual borders in order to ask unexpected and unorthodox questions in various spaces-in-between through acts of wilful intellectual trespass. I’d suggest it’s also psychically peripatetic – that its practitioners tend to take a certain rueful pride in resisting identification with any single genre, praxis, or professional category, moving on from or between these as needs must. (Which must be my excuse for delivering a presentation that no longer quite matches my original abstract).

Today, I think of open deep mapping as a walking-with the multitude of voices – both living and dead – that animate a particular place or, more accurately, sets of relationship within and between places. A walking-with that’s alert to voices, in the spirit of Richard Kearney’s ‘testimonial imagination’, that have been forgotten, marginalized or repressed by dominant narratives. And as doing so in order to re-articulate their unanswered questions in the present moment.

The book Between Carterhaugh and Tamshiel Rig: a borderline episode came out of the Debatable Lands project and was published in 2004. The symptoms of a borderline episode or personality disorder include: unstable relationships with others, confused feelings about identity, feelings of being abandoned, and difficulty controlling anger. By using that term in my title in 2004 I wanted to suggest that, for hundreds of years, the inhabitants of the Borders had enacted and suffered just those symptoms. I only realised some time later that those same symptoms had gradually come to characterise my own relationship to the academy that employed me and, as a result, had helped lead me to involve myself in open deep mapping.

The process of making the hybrid mapping piece Hidden War further emphasised my need to look for connections where they’re not expected – some would no doubt say that don’t exist. Like the Debatable Lands project, it listened to narratives shot through with fear, loss, anger, but also to their counter-narratives. Through the good offices of Mike Pearson and others, I’d been walking with a group of performers, artists and researchers in a military training area, which suggested the means to visualise the context in which my daughter Anna lives with a chronic illness that prevents her walking.

These images are of details of Tahmineh Hooshyar Emami’s Alice’s Alternative Wonderland and use a similar sense of cognitive dissonance to articulate a child’s experiences on the European refugee trail through contrasting spatial and textual renderings of the world of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and ‘Through the Looking-Glass’. Drawing on refugees’ first-hand narratives and press reports, and inspired by a reading of Carroll’s texts as political allegory, the work offers a critical analysis of the spatial politics of refuge. Carroll’s Alice, always at odds with the physical and social space of Wonderland, provides a starting point for analysing how our bodies are defined, shaped and influenced by space. Her fears and dispossession are used to highlight the experience of refugee children in a contemporary Western “Wonderland” characterised by the on-going disputes over child-refugees and their right of asylum in countries like Great Britain.

I want to suggest that open deep mapping provides an education in what Bruno Latour calls Terrestrial politics. It teaches us that a place, region or country is not exclusive, nor is it differentiated by closing itself off. It enacts Edward S. Casey’s claim that: “a place, despite its frequently settled appearance, is an essay in experimental living within a changing culture”. It demonstrates why Terrestrial co-habitation requires us to think the global through our embodied engagement with specific places. Places experienced as inclusive – as opening themselves up to multiple, diverse, sometimes contradictory, relationships, attachments and connections. And it contests the presuppositions of unidirectional professional specialisation by suggesting that, if we want to survive in the near future, we’ll need to register, maintain, and cherish a maximum number of alternative ways of belonging to the world.

However, the term “deep mapping” is now being co-opted to mean providing a digital “access mechanism” to “spatial narratives” so as to allow students “to begin a categorical inquiry”. (I’m quoting the Co-Director of the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia). Contrast that view with open deep mapping seen as a multidirectional activity. One involving: ‘observing, listening, walking, conversing, writing, exchanging, selecting, reflecting, naming, generating, digitizing, interweaving, offering and inviting’. I’m quoting Roberts again, who in turn is quoting Jane Bailey’s and my account of our open deep mapping work in North Cornwall. Fortunately, this second, more inclusive, view is still active.

In 2017 Marega Pelser contacted me, asking if we could talk about walking and open deep mapping. Marega trained as a dancer, works with movement and drawing, and is half of the performance duo Mr & Mrs Clark. We spent a day walking and talking in her home town of Newport. In time that led to me supporting her project Framing the Transient NoW (An exercise in deep mapping) in Swansea. (There’s a video of her talking about the project I’d suggest you watch). Marega’s thinking seems to me first and foremost bodily, so it was important that we walked around and about the centre of Swansea together. She finds that walking enables her, draws her attention to the micro and to things easily overlooked. It’s a way of paying attention, of observing and meeting the people that pass through a place, the objects that bang up next to each other, and the spaces in-between places. In time her walking in Swansea generated drawings and assemblages that illuminate the city centre socially, historically, and geographically – a city centre she rightly describes as “somehow absent”.

Marega’s particular take on deep mapping was to focus her attention on experiences she shared with a whole range of local people – from traders and allotment holders to the homeless, the partially-sighted and the elderly. All of whom she actively accompanied into the chaotic mixture of urban decay and development enacted in Swansea city centre. That act of accompaniment became mutual because it informed her about and illuminated the multi-faceted mixture of the new, the trivial, the old and the traumatic – with its undercurrent of uncertainty and disquiet – that constitutes that somehow absent centre of that city.

A scribbled notation on one of her maps drew my attention to an incident with a bollard. Marega had accompanied some blind, partially-sighted and wheel-chair using local people on a group walk through the city centre, using hazard tape to mark problematic obstructions. A city official challenged them as they marked a bollard. Marega explained why but was told that hazard tape was (I quote): “interfering with the structural integrity of the bollard”. So the absent city centre appears here in the disconnect between the experience of functionally impaired citizens and official concern for the structural integrity of a bollard. (However, as Marega indicated in response to a question after the presentation, it must be said that those she accompanied on the walk found it empowering).

Accompanying Marega in her work helped further shift my concern with open deep mapping towards giving more emphasis to ensemble practices and mutual accompaniment. Practices that require ways of being that require practitioners to actively distance themselves from the hyper-professionalised, unidirectional mentality rewarded by both the art world and the academy. These days, my primary concern is with ensemble practices animated by a commitment to ‘mutual accompaniment’. (A term I’ve picked up from reading the liberation psychologist Mary Watkins’ book, Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons).

In Swansea, Marega walked-alongside – or mutually accompanied – those who enacted the lived reality of a hollowed-out city centre. People who enabled her to ground her project in a genuine sense of horizontality, interdependence, and potential mutuality. The residency considered as a whole – within which I see the final exhibition as served principally as an enabling devise that gave a focus to what was very clearly a multidirectional project – points us away from the unidirectional, hyper-disciplined approaches on which academic and profession art activity are increasingly dependent, and so from the culture of possessive individualism that underpin them and which, in turn, they reinforce.

So, is my title intended to advocate that we now ‘walk away from’ deep mapping? I’m not sure. ‘Yes’ if deep mapping is reduced to a digital access mechanism for academic inquiry into categories. ‘No’, if it is understood as contributing to the growth of ensemble practices predicated on mutual accompaniment. In my view we now desperately need Hugo Ball’s commitment to the unity and totality of all things. But, increasingly, adopting that commitment means trying to find ways to live with the – let’s face it, sometimes-overwhelming dissonances and difficulties – that flow from any such commitment.

Speaking personally, open deep mapping has led me to see the desire to mutually accompany others in Mary Watkins’ sense as helping make that commitment possible. Despite the fact that it requires that I live with my own and others fear and anger – that I “stay with the trouble”, to borrow Donna Haraway’s phrase. Speaking personally, I see no other way of working towards the Deep Adaptation that Jem Bendell believes is now vital to our collective survival as a functioning society.

On Tuesday this week I spent a day helping to deliver a workshop on deep mapping to second-year architecture students at Loughborough University, the result of a kind invitation from architect, artist and architecture tutor Tahmineh Hooshyar-Emami. The students had just returned from a three-day field trip to the Debatable Land (which straddles the English/Scottish border just north east of Carlisle), so my long-running Debatable Lands project gave me the necessary background to help them to think about what factors might inform their designs for a tourist centre there. A demanding project, given the re-focusing on borders that will be an inevitable outcome of a Brexit process that deliberately presents an agenda of deregulation, the worst possible approach to social injustice and wide-spread ecocide, in the guise of an (English) call for ‘national(ist) sovereignty’ that can only reinforce the desire for Scottish independence.

The day was clearly productive for all concerned and has further provoked me to try to think though the relationships and tensions between three topics that were constantly in my mind on Tuesday, particularly as a result of my conversations with Tahmineh. The first of these is, inevitably, the nature of the practices we call ‘deep mapping’ – particularly as they sit between the arts (performance, visual arts, literatures of place) and those bodies of knowledge officially designated as the disciplines of geography, archaeology, history, anthropology, memory studies, architecture, etc. The second is the university as the institution responsible for the delivery of tertiary education and, in my view, increasingly failing to do so in any responsible way. This failure has to be of particular concern at a time when many universities are not only ducking serious ethical questions about their educational and research responsibilities at a time of rapidly deepening social and environmental crisis, but in some cases adopting tactics more appropriate to the Sopranos both to protect their research income and to deter right-minded staff from drawing attention to the consequences of their craven capitulation to the values of an increasingly toxic status quo. The third topic is the practical orientation that’s emerging out of the work of figures such as Paulo Freire so as to address the legacies of social and environmental legacies of colonialism holistically – that is identifying the causes of gross inequalities of wealth, social injustice, and environmental degradation as inextricably linked – and, with that, the social turn away from possessive individualism.

In ‘Beyond Aestheticism and Scientism: Notes towards An “Ecosophical” Praxis’ (a chapter I wrote for Brett Wilson, Barbara Hawkins, and Stuart Sim’s Art, science, and cultural understanding (2014), I referenced two posts from the blog of a respected Vice-Chancellor. Some years previously he had acknowledged that universities, supposedly the prime generators of new knowledge in our culture, had become among its most reactionary and conservative institutions. He had also indicated that their archaic position vis-à-vis society as a whole stemmed from the fact that their realpolitik (as opposed to their public rhetoric) remained deeply embedded in the presuppositions that underpin disciplinary hierarchies. Five years on all that has changed is that there has been a ramping up of the academic rhetoric of interdisciplinarity and a tightening of the managerial grip on academic thinking. Rather than undertake the difficult but necessary changes that would realign tertiary education (and by implication, education more generally) to the demands of meeting the chronic socio-environmental crisis in which we are now deeply embroiled, the ‘managerial university’ has merely increased its focus on rationalization, ‘efficiency’, and the market. (One of the ways in which this impacts on the education of students studying the arts has recently been signalled by James Elkins in a paper entitled ‘The Incursion of Administrative Language into the Education of Artists’). The link between all this and deep mapping may seem oblique in the extreme. However, as the needs of a critical, post-disciplinary education are increasingly subordinated to those of income generation, academics in ‘soft’ disciplines – that is without ‘hard’ research impact in terms of income – have had to resort to ‘sexing-up’ their curricula in order to attract the numbers of ‘customers’ required by their managerial overlords to compensate for their low status as research income generators. One result of this has been the rebranding of traditional arts and humanities departments through the creation of new areas of study such as the ‘digital’ arts and humanities. (The situation of new ‘environmental humanities’ departments and centres is more complex but, unless their staff are able to overcome their own, often deeply engrained, disciplinary bias – on which their own sense of authority often depends in a culture of possessive individualism – they will send out fatally mixed messages to their students).

In recent writing and talks I’ve been trying to get a handle on the social and environmental impact of this tripartite situation through the lens of recent developments in deep mapping. In part by referencing its appropriation by academics in the ‘spatial’ and ‘digital’ humanities, and in part by indicating how ‘open’ deep mapping has begun to mutate, to help inform what the liberation psychologist Mary Watkins calls ‘mutual accompaniment’ in her recent book Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons (Yale University Press, 2019). My aim in all this is to show that deep mapping, in the context of moving towards an education fit for purpose at a time when what is required is Deep Adaptation, must itself be prepared to rethink what is to be understood by the adverb ‘deep’ in relation to issues of place, displacement, and placeless-ness.

My sense at present is that this will require us to de-couple ‘deep mapping’ from its links with the roll of ‘Artist’ (capital A) – a designation now fatally infected by its adoption as poster-person for the ‘creative’ within possessive individualism. The alternative is to acknowledge what has always been the case with open deep mapping. That those who undertake it have always had ensemble practices, practices in which the function of their ‘art’ skills is to help constitute a multidirectional activity by animating and complicating the host of other, often more pragmatic and instrumental skills, with which those ‘arts’ skills are aligned. The resulting ensemble practice is, as a result, polyvocal and horizontal in its operational structuring; unlike the traditional univocal approach of the Artist in which all other skills and concerns are subordinate to the needs of a single monolithic identity.

It’s not a position I expect many people to be prepared to grapple with, let alone adopt, given the massive investment in the artistic ego and its unidirectional goals required to ‘succeed’ in the dominant culture. However, at present I can see no other alternative, given the terrible situation in which we find ourselves culturally, politically and environmentally.

Félix Guattari argues that we need new configurations of three fundamental and interwoven ecologies – the environmental, the social and the psychic – if we are to address our now toxic situation. It has seemed to me for a good while now that artists, while they may pay lip service to Guattari’s thinking, simply don’t take the ecology of the psyche seriously enough. (Perhaps because they rightly sense that to do so might raise questions that are too close to home for comfort). Yet we are deeply embedded in a culture in which psychic problems of addiction, depression, self-harm and suicide are rapidly growing, not to speak of wider issues like the gap between rich and poor, the national disgrace in the UK of growing levels of child poverty, and the related need for food banks. All of which are indications of a shriving away of the empathetic imagination proper to understanding what constitutes human selfhood. In this grim situation, we obviously need all the help we can get to identify and address the root psychic causes of what is happening all around us.

These thoughts, or variations on them, have been with me all summer as I’ve struggled with a familiar problem. How do I make any sense of and write about the increasingly dangerous and uncertain situation we’ve arrived at and, in particular, of the role of the arts in the culture of possessive individualism out of which that situation has grown. In the last few weeks help with this thinking has come from an unexpected source. I’ve read and re-read Madeline Miller’s novel Circe, a retelling of many of the elements of the Odyssey, seen from the perspective of the nymph, and later witch, Circe. I have been fascinated by Greek myths since I read Robert Greaves’ re-telling of them in early adolescence; a fascination later deepened by my reading of authors such as James Hillman, Ginette Paris, Mary Watkins and Edward S. Casey. Much of which has, no doubt, been at the back of my mind while I read Miller. (Her book has been called an example of ‘feminist revisionism’, but for me such a dry academic term misses so much that makes it compelling as a novel).

It has helped my thinking because it seems to me to identify and challenge two interwoven and fundamental aspects of possessive individualism – the myth of the hero (usually male, but in today’s culture of any gender), and the cult of fame (our culture’s substitution for “immortality”) which, taken together, orient our culture’s obsession with individual exceptionalism, the desire for attention-grabbing achievement or celebrity to be won regardless of the cost to one’s own humanity, to others, or to the world at large. Consequently, Miller’s evocation of Circe’s final act, her preparation to use the full strength of her knowledge and power to renounce her own immortality, is every bit as important to Miller’s story as her skilful deconstruction of Odysseus’ status as a hero.

There is a passage late in the book that brought me close to tears because it seems so extraordinary relevant to our current situation and to the questions I’ve been asking myself. It involves a conversation between Circe and Telemachus, the son of Odysseus and Penelope who, with her, has found refuge with Circe. (They hope of escape the attention of the Goddess Athena, the force behind Odysseus’ insatiable desire for fame through cunning, trickery and ruthlessness). The two of them are discussing levelling the uneven flagstones in her courtyard. As Telemachus begins the job, Circe points out that their uneven wobble is caused by roof water draining there and washing away the soil. Whatever he does, the wobble will return after the next rain. His reply begins a passage that, for me, is the heart of the book: ‘that is how things go. You fix things, and they go awry, and then you fix them again’.

What follows offers a telling account of an alternative to the heroic model based on exceptionalism. It counters its failure to acknowledge what really drives our restless “scientific” curiosity, our desire for novelty, our desire to move on so as to find new, attention-grabbing challenges to meet and problems to solve. Its failure to acknowledge and celebrate the absolute necessity to human community and solidarity of sharing attention to ‘how things go’. Of attending to their inevitable ‘going awry’, and the central importance of our willingness and ability to patiently return to the task of fixing them yet again. And within this the central importance of taking pleasure ‘in the simple mending of the world’, as Circe puts it later in the book.

All that happens later in the book flows from Telemachus’ seeing through, and rejecting, the seductive image of the hero his father once embodied for him. Despite everything that Athena offers him, he makes it very clear that he has no wish to emulate his father. Instead he accepts that our being truly human requires us to recognise that, when things inevitably go wrong, that is simply how the world is. That we must then fix them as best we can, recognising that they will go awry again and that we, or those who follow us, will then have to fix them yet again. An honouring of the solidarity t be found in facing basic human necessities, rather than the desire for the exceptionalism of the hero.

Given what we know of the relationship between some current political players and their fathers, this passage takes on a particular relevance. But (for once) I will resist the temptation to be trite and dwell on such individuals. (If you are a regular reader of this blog, you won’t need to guess who I have in mind). This is not, however, an issue of “individual psychology” (itself a problematic and potentially misleading phrase). It’s about a fundamental presupposition that helps underpin the entire “globalised” culture of consumer capitalism. (And, of course, the “success” of artists like Jeff Koons, which depends on the warping of our sense of creativity and imagination in the name of novelties that can be easily and conspicuously consumed by the super-rich). Until we face the psychic issues that that presupposition generates, in whatever way each of us can, those who see themselves as “artists” in the heroic mode will remain just what the performance art Andrea Fraser has named them, part of the problem, not part of the solution.

.