(Image: Max McClure)

Preface

What I’ve written below is a partial, gappy, highly subjective ‘translation/transcription-after-the-event’ of an action into a text. Perhaps ironically, it responds to what I take to be, at least in part, two artists’ calculated move away from the cerebral analytics that make up many reflexive texts. The partiality and gappiness are inevitable. I can’t pay close attention to a complex unfolding sequence of actions involving two people over two hours plus and, simultaneously, write sensible notes. Since the action itself was a lens through which a sense of the everyday is re-visioned, and because its ‘audience’ occupied and moved within the same space, each person there very obviously had her or his unique, moment-to-moment sense of it’s numerous consecutive interactions within a layered physical and (larger, and highly porous), aural space, together with the multitude of metaphorical resonances those interactions activate.

I

(Image: Max McClure)

For example, I doubt whether anybody else witnessed one brief, particular and significant conjunction of bodily stances I caught a glimpse of. I just happened to be where I could catch sight of Laila Diallo unfolded from a particular posture at the very moment when a be-suited man, deep in conversation on his mobile, crossed behind her going down the short section of passageway that’s visible from the gallery. A man who was clearly absent from that space in all but the most literal sense, entirely absorbed and so wholly oblivious to Laila out on the edge of his peripheral vision.

(Image: Max McClure)

That momentary juxtaposition, between an attentive and carefully articulated bodily unfolding and a ‘being elsewhere’, an important aspect of Edge and Shore appeared in sharp relief. It illuminated the actants’ inclusiveness, their attention and openness to contingency, happenstance, and the influx of the past – for example to the effects of the previous day’s experiences, which they could not help but bring to the work. It is this apparently artless openness that, I think, helps give their work its particular qualities. Its articulating of a ‘something’ as yet unnamed, a brave opening out beyond the dominant aesthetics of exclusion into another, more generous, sociability. Here the craft and riskiness of attentive improvisation wanders its way along a fine and delicately judged path between two possibilities.

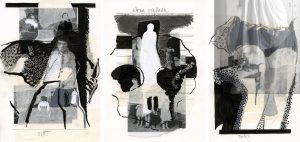

(Image Helen Carnac)

It could very easily have been a working through that, freighted with multiple mundane actions that evoke the muddle, mess and repetition of daily life, would simply leave us psychically swamped, mired in metaphorical overload and the cacophony of our own emotional feedback. Equally, it could easily have gone the other way. It could have been a merely artful formal play with the numerous properties of space, movement, and materials; a seductive but ultimately cerebrally-oriented flirting with the dangers of raw evocation and metaphor that stylishly skirted over all the deeply sedimented layers of unsettling meaning and affect latent below its artful surface. (Artful ‘dry humping’ masquerading as passionate polymorphous entanglement).

(Image Helen Carnac)

Edge and Shore: Acts of Doing

I was invited by Helen Carnac to take part in an evening conversation with Laila Diallo and herself at the Arnolfini on the evening of July 8th. So I arranged to join them that morning for the first iteration of their Edge and Shore: Acts of Doing. As I understand it, their understand their collaboration as located somewhere off to one side of performance and installation; as setting out to do pretty much what it’s title implies: survey the edges of place and practice through those ‘acts of doing’ familiar to them as an artist/maker and dance artist. (Hence my use of Alastair McLennan and Joseph Beuys’ term ‘action’ and my reference to Helen and Laila as ‘actants’ here).

(Image Helen Carnac)

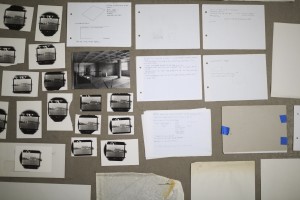

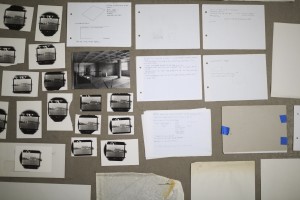

When I arrived at the Arnolfini I walked through to the ground floor gallery, now set out with various materials, many carried over from Laila and Helen’s previous Edge and Shore residency at the Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh. (These included long lengths of thick, well-used looking and drawn on rolls of paper stood on end or hung, two video projections, boxes of materials of various sorts, and a large cluster of assorted overlapping photographs fixed to one wall). My arrival is noted and Laila appeared almost at once, a thin, animated figure who greets me warmly. Helen soon follows – she has been hunting for a lost box in which they have collected the sheets of A4 paper with the words they’ve used – and we talk about the qualities of the space, the assembled objects, and the floor with its rich staining of traces from previous exhibitions. They both seem to relish the possibilities offered by these traces as another, unfamiliar, set of material memories.

(Image: Max McClure)

As soon as I arrived I was drawn into the intimate tenor of the space by the projected images of hands involved in a game (some cross between Jenga and Paper, Scissors, Stone) My expectations are of play in its widest sense.

Helen and Laila quietly start to prepare the space and I settle myself on one of the low benches provided. As they begin to speak together and then move about the space I catch myself drifting into the particular analytical state of mind of my ‘inner external examiner’. I make a conscious attempt to avoid being caught by this.

Words start to appear on the blank sheets of paper the actants have distributed around the room.

SMILE

BETWEEN

TRAFFIC

LAUGHTER

NOTICING

There is at once a sense that the physical space, its current inhabitants, and its aural permeability, are all being audited, both openly and in more coded terms.

PASSING

ORANGE

AT PACE

4

… and so on.

Their interactions during this audit are apparently casual but, at a given point, take on a greater sense of focus as the sheets with their hand-written words are collected up and thoughts quietly exchanged between the actants. The words are then read out loud by the two of them in turn and an editing process takes place, with Laila dropping selected sheets onto the floor.

(Image: Max McClure)

There is a shift – a clear concentration – of the action. The wooden table near the wall is cleared, becomes a theatre for hands, and an assortment of wooden blocks, many of them with blue painted ends, appear (the ‘Jenga blocks’ from the video). Helen and Laila begin a process of exchange based on offering each other vertical and horizontal permutations of clusters of these blocks, with Helen’s tending to emphasise the vertical and Laila’s the horizontal. In this subtle articulation of difference between the two women words have been replaced by permutations that enact a conversational exchange. They are pushed back and forth across the surface of the table, with the proximity of the different groupings to the edge nearest each becoming increasingly resonant. (Questions like ‘whose exchange will be pushed over the edge’ are begged, and I am caught up in every nuance of exchange, bound more intimately into the relationship between these two woman).

This unfolding and sometimes noisy process of exchange crackles with the energy of a real working relationship, its moment-by-moment pulls and pushes, and distinctive characterisations appear, articulated through each gesture, facial expression, and shift of bodily stance. After a while Laila changes the dynamic, using the blocks to map the space in which her hand rests. Helen responds by building her hand space into Laila’s. There is a palpable sense that a dynamically tensioned but empathetic relationship has been established, only to be let go off shortly after.

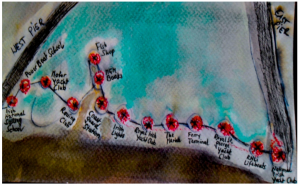

(Image: Max McClure)

This intense, bodily, wordless dialogue now concluded, Laila moves some of the blocks to the floor. Helen, by contrast, starts another ‘build’ on the table until she, too, transfers her wooden blocks onto the floor. As if now sure of the ground of their interactions, the two actants allow their activities to bifurcate. Helen works with the blocks – as I later discover offcuts from her partner’s work as a cabinet maker- down on the floor. She is enclosing the trace of words that formed part of a previous exhibition, including the word ‘consciousness’, while Laila begins to mark out the larger space of the room itself. Her slightly erratic progress draws attention to its being full of stuff, to her use of her body for a form of ‘mapping’, to a sense of provisionality that is amplified by the fragility of her hold on the cluster of blocks in her hands.

On perhaps the third circuit – it’s easy to loose count when you’re taking notes – a woman watching (who has left Laila little space to pass), is drawn directly into the action. Squeezing past her, and seeing that one of her hands is upraised and open, Laila gives her some blocks to hold. In that instant, the whole tenor of the room changes. Those of us watching can no longer locate ourselves, however tacitly, on the outside, as passive spectators. The assumption of an invisible wall between the ‘performers’ and ourselves has been put in question. Now the entire space is an active palimpsest, is loosened and made more permeable in innumerable new ways.

Like the over-eager child at a party who is not picked to help the conjuror, I find myself unreasonably jealous of my co-spectator turned momentary actant. I want that moment of intimate shock, of immediate physical exchange.

My whole challenge now is to somehow keep in view the double process of mapping/enclosing of space and all this involves. Two counterpointed processes are emerging. Helen’s activity appears primarily oriented by her manipulation of materials, Laila’s by the use of her body as a means of marking out, ‘measuring’, the space – pacing, high-stepping, stretching out, jumping. After a while Laila collects up the blocks that she’s been using as part of her marking out and brings them back to Helen’s space in a moment of convergence.

(Image: Max McClure)

My response to this is best described in an image. A circling child returns to her mother to take assurance from ‘touching base’, soliciting approval by bringing back some small gift. This image is reinforced by the steady practicality of Helen’s sorting of the returned wooden blocks. I am quickly caught up in the mesh of resonances between the two women, now both amplified and confused by my provisional categorising of them as ‘grounded mother’ and ‘restless daughter’. But the feeling attached to this categorisation also lends a tenderness to the unfolding actions.

Emerging from the distance of my own imaginal reverie, I am just in time to catch a pregnant pause while the two actants consult together, the hushed mutter of a large orchestra between symphonic movements. But that thought in turn quickly develops it’s own trajectory. Perhaps the whole work could be read as a musical score, perhaps by John Cage. I am again brought back into the moment by catching sight of Laila starting to move on the spot in such a way as to open up a truncated gestural space through the near-repetition of movements that appear invisibly circumscribed.

Meanwhile Helen has started to methodically straighten out and roll up a long length of bright orange tape. Her preparations complete she uses this to delineate a new space, but in a way that’s quite distinct from the previous foursquare use of wooden blocks as miniature ‘walls’. This new, taped space is somehow flamboyant, almost Baroque, with its ragged, scalloped edges. It now encircles Laila. Helen starts to loop the orange tape up and pin it in short, luxurious swags on the taught surface of the hanging sheet of paper. (This has been serving as a significant edge space for some minutes). Ruched curtains and Mary’s Lorna – both child and sophisticate – comes pirouetting into my thoughts, showing off some party dress for an end-of-term dance). Each of Helen’s pinnings produces a small, densely resonant sound, like a small parchment drumhead being sharply tapped once with a hard stick. And each sounding reverberates powerfully against the background of thick aural soup that, as I now realise, almost continually permeates the space.

(Image: Max McClure)

Laila continues her singular movements, as if trying either to perfect them or else complete them despite what is, invisibly, circumscribing them. I worry that these movements are exhausting her, a concern reinforced by her lying flat and breathing heavily at intervals. It’s impossible to know whether this ‘worry’ on my part is in response to the intensity of my own, possibly inappropriate, emotional involvement – a by-product I suspect of my daughter Anna’s long, debilitating illness – or simply a legitimate response to Laila’s exertions. Perhaps it’s both.

At this point both my notes and my memory entirely fail me.

I find on reading them that I wrote: “she [Laila] inserts her body into the space Helen had enclosed earlier”. Yet according to my own narrative above Laila never left that space. Memory, shaky at the best of times, is no help here. I’m at a loss, simply unable to reconstruct what happened although, thinking back, I’m fairly sure Laila had been moving at some distance from Helen’s ribbon-space.

(Image: Max McClure)

What’s clear from what I can call to mind is that, at some point, the two actants had moved much closer to each other. Helen worked at scrapping and tracing over a section of the floor, much as one might make a brass rubbing from a tomb in an old church. Laila’s actions at this point were gradually encroaching on the particular area of floor space where Helen was working. Again there’s a slight disturbance that I quickly rationalise through an image. A child tries to attract her mothers’ attention in a roundabout way and then feels excluded because her mother misses the cue. There’s both the desire for intimacy, for a transgressing of personal space, and at the same time the fear of doing it. No sooner has this passed through my mind than Laila moves away to occupy a zone Helen had worked in earlier.

(Image: Max McClure)

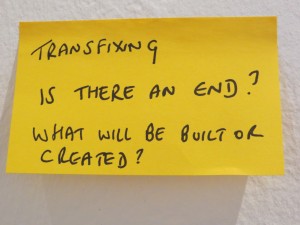

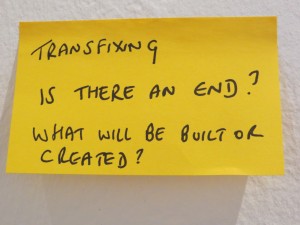

As if pushed out to the extremities of the space, Laila has now located herself up against a wall near where I sit. Helen, unperturbed, continues to work with and mark the space she has occupied, hunkered down to tap or dot out her traces on paper using a block of wood. (This description is partly conjecture – and certainly inexact – since Helen’s half hidden behind a screen of hanging paper that prevents me from seeing many of her actions, although I hear them very clearly). Laila, now hunkered down by the wall, hesitantly starts to tap her thigh with the fingers of her left hand. She seems about to pick up Helen’s rhythm when it falters and dies away. Laila simply stands up and walks diagonally across the room to write a post-it note that she then sticks to the wall. From my bench I cannot read what she has written.

I am a little envious of how easily each actant seems to move between actions and, I assume, their accompanying mental and emotional states.

Laila has returned to her earlier series of truncated gestural movements but now oriented by a linear movement. Helen stops what she has been doing and moves to a bench by the wall. Again, there’s that sense of an orchestra pausing, of a silence immediately filled by the soupy background hum of noise that once again foregrounds itself.

(Image: Max McClure)

Helen crosses the room and unfolds a cloth, before laying out a variety of materials – photographs, drawings, and short fragments of text – on the floor around it. I have a sudden memory of Gini’s Stony Rises deep map – it’s palimpsest of layers, drawings and transparencies, its votive stones and miniature video screens. Laila continues her movements. Am I projecting onto her a vague sense of being increasingly trapped and uncomfortable in her movements, over there up against the wall again? And if so, why? Suddenly she breaks off, picks up a roll of paper, and joins Helen. Again that easy moving between states, that simply letting go. Helen’s layout becomes more extensive, with various repetitions of small black and white photographic images.

(Image: Max McClure)

At this point my attention got divided without my really noticing that this has occurred. While mentally I continued to observe and write notes, my emotional state (now left to its own devices), started to drop, no longer buoyed up and carried along by the flow of the action. In retrospect I think I simply got more and more bogged down in a muddle of conflicting emotional responses to what was unfolding. But I only became conscious of this when I wrote: “Suddenly Samuel Beckett comes to mind”.

Helen is now tearing words from a long sheet of paper and the two actants reconnect. The rolling out of a long line of paper then gives Laila a new direction for movement, but this somehow seems no less ‘pained’ than before, given its halting slowness. The photographer who unobtrusively stalks her across the floor suddenly conjures up the image of Laila as a wounded animal, one that is trying to drag itself to a place of safety away from the hunter who tracks it.

As if in response to my sinking mood, an angry man suddenly breaks into the space around which we’re gathered and demands in a loud voice to know if we the audience think this is ART? Thrown and irritated in equal measure, I challenge his assumptions and a short but clearly pointless exchange follows. He wants ART that offers us Truth, Beauty, History, (and for reasons that escape me, Archaeology) on a plate, but oddly the image he chooses to support this is the Arnolfini Wedding. I do NOT ask him, for reasons that should be self-evident, how or why an early celebration of a commercially motivated amalgamation of business interests in the form of a bourgeois marriage contract embodies these qualities. He leaves with his wife and child. His anger is, however, in marked contrast to their earlier responses. The mother simply expressed mild puzzlement as to the ‘rules of the game’ being played, while the child just wanted to join in by playing with the wooden blocks.

As my attention returns to the action there is a strong sense of words as stuff, matter to be manipulated, put to work, discarded.

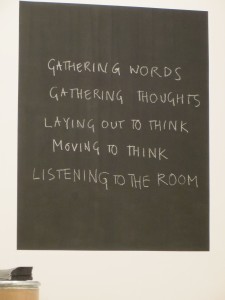

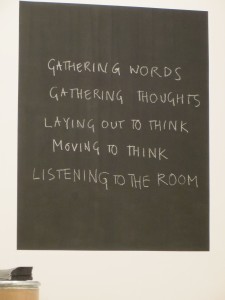

Helen rolls up one of the long scrolls on which the gathered words have been written, while Laila circles one of the large sheets of paper on the floor. On the blackboard on the short wall next to the passage Helen writes:

GATHERING WORDS

GATHERING THOUGHTS

LAYING OUT TO THINK

Increasingly our language seems to me cripplingly inadequate, reductive, off the mark and, it must also be said, crassly abused. Why don’t we have a word for what James Hillman, following several older traditions, calls ‘the thought of the heart’, a word for heartfelt, embodied thinking? That’s the word I want to replace Helen’s THOUGHTS and TO THINK on the board. But surely part of all that I’ve just experienced tells me that we have to work with the potential of what we’ve got, at least as a starting point in the here and now?

(Image: Max McClure)

Laila has stopped circling and returns to her previous ‘on the spot’ sequence of movements. Later she will follow one of the lines of paper, a slow, hands and knees movement that feels like a winding down. A hill walker working her way up scree, the last effort before home at the end of a long day’s ramble through the high hills.

Helen meanwhile pins torn words and letters to the back of a semi-transparent hanging screen that turns one corner of the room into a darker, store-like space. This action feels like a lining, or insulation of that area, but one that’s highly ambiguous in its relationship to the words that are repositioned, even destroyed, by her actions. There is a real sense of persistence in this action that, despite its sense of inwardness, seems profoundly protective. Is a shelter being prepared, a dwelling-place, but if so for whom and, of course, against what?

(Images: Max McClure)

There is no real sense of a ‘drawing to an end’, more of a ‘circling back’. Laila has started to mark out a new space within the room using the smallest wooden blocks, some no bigger than a postage stamp. Again she is stretching and semi-falling as she does so. She then reverses the process, retracing her movements and gathering up her little wooden markers as she does so. All the time I am very conscious of her bodily exertions, of the fact that she’s been on the move for over two hours, as frenetic as Helen is calm. Laila repeats the action of marking out a space within the room, but in another, slightly more modest configuration, coming and going behind the hanging sheets as she does so.

(Image: Max McClure)

Helen has now moved from pinning to balling up the pieces of paper with their letters and words. These are formed into tight, roughly fist-sized, objects. She lays a good number of them out in careful rows behind her sheltering screen as if preparing snowballs for a fight.

Later we will sit over our food and talk, roughing out what we might say about the work during the scheduled public conversation that evening. We speak together of forms of mapping, about memory, noticing, Tim Ingold on lines, about making, habits, and accumulation. Laila, based in Bristol, must leave soon to attend to her son and our discussion of the work is now casually interleaved with talk of child-care arrangements and his grandmother’s willingness to make cupcakes for a school event.

I am immensely grateful for this seamlessness in our speaking together, this easy camaraderie in the transition from one constellated event to another in our briefly mutual polyverse. And perhaps that is what I will most value in what I take away from my day’s exchange with Helen and Laila.

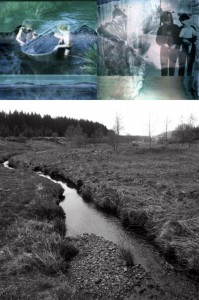

(Image: Helen Carnac)

At one point, during our post-event discussions, a connection appeared to me between the underlying tenor of the morning’s action and certain old folk songs. Both it seems are in part concerned, beneath any literal ‘narrative’, with the virtues and possibilities of living with the mundane, the repetitious, the overlooked, and with inevitable failure in our lives (‘even unto death’), but also of doing so with canny attention, with a certain lightness of spirit or dark humour (depending on our temperament) and, of the utmost importance, in good company.

(Image: Helen Carnac)

Postscript.

Helen and I spoke on the phone for just short of an hour prior to the event I’ve tried to evoke here. We were happily teasing out elements of our mutual interests and following up various threads of thought as they appeared. This turned out to be an ideal preparation for what I would experience on July 8th. A good part of that initial exchange circled around issues of attention and, having referred to Kathleen Jamie’s observations, I sent Helen this.

‘Kathleen Jamie refers to attention as follows. When asked if she had prayed for her dangerously sick partner when he was in hospital, her response was that she hadn’t. She adds, however, that she:

“… had noticed, more than noticed, the cobwebs, and the shoaling light, and the way the doctor listened, and the flecked tweed of her skirt, and the speckled bird and the sickle-cell man’s slim feet. Isn’t that a kind of prayer? The care and maintenance of the web of our noticing, the paying heed?”’ (Jamie, 2005: 109)

Without that ‘paying heed’ there can be no empathy, no sense of an aesthetic of the everyday, and without imaginative empathy no politics of nurture worth the name, no concern for the Commons. For those of us who do not want to live under the authoritarian oligarchy that currently passes for democracy in the UK, an oligarchy with its roots in the world-view celebrated by Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Wedding, ‘paying heed’ is now a political obligation. I would have liked the courage and presence of mind to say that to the angry man. To have made clear to him that Art, Truth, Beauty, and History have now all-too-often been co-opted, empty power words. Words that are part of the armoury at the disposal of people whose every action flies in the face of ‘paying heed’, who are fully paid up members of a culture of possessive individualism that is psychically, socially and environmentally toxic.

These are, of course, my own personal preoccupations and interpretations and I have no wish to or intention of fostering them onto Helen and Laila. However, they do reflect something of what I take away from my time spent with them.

(The images above are used here were taken by and are used here by kind permission of Max McClure and Helen Carnac)